ديوكلتيانوس

| ديوكلتيانوس | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| امبراطور الامبراطورية الرومانية | |||||||||

ديوكلتيانوس | |||||||||

| العهد | 20 نوفمبر 284 - 286 (بمفرده); 286 - 1 مايو 305 (بلقب أغسطس الشرق, مع ماكسيميان بلقب أغسطس الغرب) | ||||||||

| سبقه | نومريان | ||||||||

| تبعه | |||||||||

| Co-emperor | Maximian (في الغرب) | ||||||||

| وُلِد | ح. 245 ديوكليا، بالقرب من صالونا | ||||||||

| توفي | ح. 316 سبليت | ||||||||

| المدفن | |||||||||

| الزوج | Prisca | ||||||||

| الأنجال | Valeria | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| الديانة | Roman polytheism | ||||||||

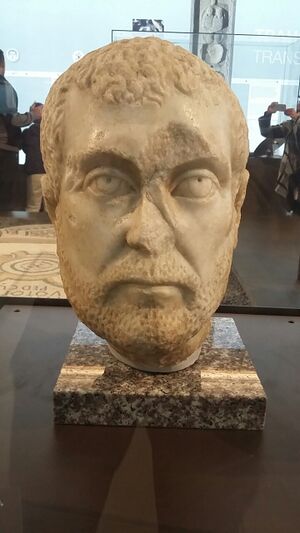

ديوكلتيانوس أو دقلديانوس (إنگليزية: Diocletian؛ /ˌdaɪ.əˈkliːʃən/، أو گايوس أورليوس ڤالريوس ديوكلتيانوس (لاتينية: Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus)؛ و. 22 ديسمبر 224 - ت. 3 ديسمبر 311)، كان امبراطوراً رومانياً من 284 حتى 305. وُلد في مدينة سالونا بولاية دالماشيا بإقليم إيليريا المطل على البحر الأدرياتي شمال إيطاليا لعائلة فقيرة، وانضم إلى طبقة الفرسان ووصل إلى رتبة دوق (أي قائد الفرسان) في ولاية ميسيا، ثم أصبح قائد قوات الحرس الامبراطورى الخاص وهي من الوظائف الخطيرة، وتجلت كفاءته العسكرية في حرب فارس، وبعد وفاة الامبراطور نوريانوس (283 – 284) اعترف به بأنه أجدر شخص بعرش الامبراطورية.

Diocletian's reign stabilized the empire and ended the Crisis of the Third Century. He appointed fellow officer Maximian as Augustus, co-emperor, in 286. Diocletian reigned in the Eastern Empire, and Maximian reigned in the Western Empire. Diocletian delegated further on 1 March 293, appointing Galerius and Constantius as junior colleagues (each with the title Caesar), under himself and Maximian respectively. Under the Tetrarchy, or "rule of four", each tetrarch would rule over a quarter-division of the empire. Diocletian secured the empire's borders and purged it of all threats to his power. He defeated the Sarmatians and Carpi during several campaigns between 285 and 299, the Alamanni in 288, and usurpers in Egypt between 297 and 298. Galerius, aided by Diocletian, campaigned successfully against Sassanid Persia, the empire's traditional enemy. In 299, he sacked their capital, Ctesiphon. Diocletian led the subsequent negotiations and achieved a lasting and favorable peace.

Diocletian separated and enlarged the empire's civil and military services and reorganized the empire's provincial divisions, establishing the largest and most bureaucratic government in the history of the empire. He established new administrative centres in Nicomedia, Mediolanum, Sirmium, and Trevorum, closer to the empire's frontiers than the traditional capital at Rome. Building on third-century trends towards absolutism, he styled himself an autocrat, elevating himself above the empire's masses with imposing forms of court ceremonies and architecture. Bureaucratic and military growth, constant campaigning, and construction projects increased the state's expenditures and necessitated a comprehensive tax reform. From at least 297 on, imperial taxation was standardized, made more equitable, and levied at generally higher rates.

Not all of Diocletian's plans were successful: the Edict on Maximum Prices (301), his attempt to curb inflation via price controls, was counterproductive and quickly ignored. Although effective while he ruled, Diocletian's tetrarchic system collapsed after his abdication under the competing dynastic claims of Maxentius and Constantine, sons of Maximian and Constantius respectively. The Diocletianic Persecution (303–312), the empire's last, largest, and bloodiest official persecution of Christianity, failed to eliminate Christianity in the empire. After 324, Christianity became the empire's preferred religion under Constantine. Despite these failures and challenges, Diocletian's reforms fundamentally changed the structure of the Roman imperial government and helped stabilize the empire economically and militarily, enabling the empire to remain essentially intact for another 150 years despite being near the brink of collapse in Diocletian's youth. Weakened by illness, Diocletian left the imperial office on 1 May 305, becoming the first Roman emperor to abdicate the position voluntarily. He lived out his retirement in his palace on the Dalmatian coast, tending to his vegetable gardens. His palace eventually became the core of the modern-day city of Split in Croatia.

كان اسم دقلديانوس الحقيقى (ديوقليز) وقد اختار اسم دقلديانوس بعد أن اعتلى العرش واتخذ دقلديانوس لنفسه تاجاً (عصابة عريضة مرصعة بالآلئ) وأثواباً من الحرير والذهب، وأحذية مرصعة بالحجارة الكريمة. وابتعد عن أعين الناس في قصره، وحتى على زائريه أن يمروا بين صفين من الخصيان والحجاب وأمناء القصر ذوى الألقاب والرتب، وأن يركعوا ويقبلوا أطراف ثيابه.

وكان عصر دقلديانوس نقطة تحول في التاريخ القديم من عصر الامبراطورية الرومانية إلى العصرالبيزنطي عندما اعتلى دقلديانوس عرش الامبراطورية الرومانية في سنة 284 ميلادية حاول إدخال بعض الاصلاحات بإدماج ولايات وتقسيم ولايات أخرى. وقسمت مصر التى كانت حتى ذلك الوقت ولاية واحدة إلى ثلاثة أقسام يحكم كل قسم حاكم مدني أما السلطة العسكرية فقد وضعت في يد قائد يسمي دوق مصر.[1]

وكان مكسيميانوس شريك دقلديانوس في حكم الغرب

النشأة

كان ديوكلتيانوس ابن معتوق دلماشي. وكان ديوقليشيان أو دقلديانوس - وهو الاسم الذي اختاره بعد ذلك لنفسه - قد ارتقى بمواهبه الفذة ومبادئه الأخلاقية المرنة حتى عين، وحاكما في بعض الولايات، وقائداً لحرس القصر. وكان رجلاً عبقرياً أكثر دراية بشئون الحكم منه بالحرب. وقد جلس على العرش بعد عهد من الفوضى أشد من الفوضى التي عمت البلاد من أيام ابني جراكس إلى أيام أنطونيوس، ولكنه هدأ كل الأحزاب الثائرة المتنافرة، وصد الأعداء عن جميع الحدود، وبسط سلطان الحكومة وقواه، وأقام حكمه على تأييد الدين ورضاء رجاله. وكان ثالث ثلاثة تدين لهم الإمبراطوريّة بالشيء الكثير - أغسطس وأورليان؛ ودقلديانوس. وأما أغسطس فقد أنشأها، وأما أورليان فقد أنقذها، وأما دقلديانوس فقد نظمها تنظيماً جديداً.

وفاة نومريان

Carus's death, amid a successful war with Persia and in mysterious circumstances[2] – he was believed to have been struck by lightning or killed by Persian soldiers[3][4] – left his sons Numerian and Carinus as the new Augusti. Carinus quickly made his way to Rome from his post in Gaul and arrived there by January 284, becoming the legitimate Emperor in the West. Numerian lingered in the East.[5] The Roman withdrawal from Persia was orderly and unopposed.[6] The Sassanid king Bahram II could not field an army against them as he was still struggling to establish his authority. By March 284, Numerian had only reached Emesa (Homs) in Syria; by November, only Asia Minor.[5][7] In Emesa he was apparently still alive and in good health: he issued the only extant rescript in his name there,[8][Note 1] but after he left the city, his staff, including the prefect (Numerian's father-in-law and the dominant influence in his entourage)[11] Aper, reported that he suffered from an inflammation of the eyes. He traveled in a closed coach from then on.[7] When the army reached Bithynia,[5] some of the soldiers smelled an odor emanating from the coach.[6] They opened its curtains and found Numerian dead.[5][12] Both Eutropius and Aurelius Victor describe Numerian's death as an assassination.[13]

Aper officially broke the news in Nicomedia (İzmit) in November.[14] Numerianus' generals and tribunes called a council for the succession, and chose Diocles as Emperor,[5][15] in spite of Aper's attempts to garner support.[14] On 20 November 284, the army of the east gathered on a hill 5 كيلومتر (3.1 mi) outside Nicomedia. The army unanimously saluted Diocles as their new Augustus, and he accepted the purple imperial vestments. He raised his sword to the light of the sun and swore an oath disclaiming responsibility for Numerian's death. He asserted that Aper had killed Numerian and concealed it.[16] In full view of the army, Diocles drew his sword and killed Aper.[17] According to the Historia Augusta, he quoted from Virgil while doing so.[18] Soon after Aper's death, Diocles changed his name to the more Latinate "Diocletianus"[19] – in full, Gaius Valerius Diocletianus.[Note 2]

النزاع مع كارينوس

After his accession, Diocletian and Lucius Caesonius Bassus were named as consuls and assumed the fasces in place of Carinus and Numerianus.[21] Bassus was a member of a senatorial family from Campania, a former consul and proconsul of Africa, chosen by Probus for signal distinction.[22] He was skilled in areas of government where Diocletian presumably had no experience.[14] Diocletian's elevation of Bassus symbolized his rejection of Carinus' government in Rome, his refusal to accept second-tier status to any other emperor,[22] and his willingness to continue the long-standing collaboration between the empire's senatorial and military aristocracies.[14] It also tied his success to that of the Senate, whose support he would need in his advance on Rome.[22]

Diocletian was not the only challenger to Carinus' rule; the usurper Julianus, Carinus' corrector Venetiae, took control of northern Italy and Pannonia after Diocletian's accession.[23][24] Julianus minted coins from Siscia (Sisak, Croatia) declaring himself emperor and promising freedom. This aided Diocletian in his portrayal of Carinus as a cruel and oppressive tyrant.[25] Julianus' forces were weak, and were handily dispersed when Carinus' armies moved from Britain to northern Italy. As the leader of the united East, Diocletian was clearly the greater threat.[23] Over the winter of 284–85, Diocletian advanced west across the Balkans. In the spring, some time before the end of May,[26] his armies met Carinus' across the river Margus (Great Morava) in Moesia. In modern accounts, the site has been located between the Mons Aureus (Seone, west of Smederevo) and Viminacium,[22] near modern Belgrade, Serbia.[27]

Despite having a stronger, more powerful army, Carinus held the weaker position. His rule was unpopular, and it was later alleged that he had mistreated the Senate and seduced his officers' wives.[28] It is possible that Flavius Constantius, the governor of Dalmatia and Diocletian's associate in the household guard, had already defected to Diocletian in the early spring.[29] When the Battle of the Margus began, Carinus' prefect Aristobulus also defected.[14] In the course of the battle, Carinus was killed by his own men. Following Diocletian's victory, both the western and the eastern armies acclaimed him as Emperor.[30] Diocletian exacted an oath of allegiance from the defeated army and departed for Italy.[31]

الحكم المبكر

وكان أول قراراته الحاسمة قراراً كشف عن المستور من أحوال الدولة وعن أفول نجم رومة، فقد هجر المدينة ولم يتخذها عاصمة لملكه، واتخذ مقامه في نيقوميديا وهي مدينة في آسية الصغرى تبعد عن بيزنطية بقليل من الأميال جهة الجنوب، وظل مجلس الشيوخ يعقد جلساته في روما كما كان يعقدها قبل، وظل القناصل يقومون بمراسمهم المألوفة، وظلت الألعاب الصاخبة تدور كسابق عهدها والشوارع تموج بمن فيها من الناس على اختلاف أجناسهم؛ ولكن السلطة والقيادة قد انتقلتا من هذه المدينة التي أضحت مركز الانحلال الاقتصادي والأخلاقي. وكان الذي دفع دقلديانوس إلى هذا العمل هو الضرورة الحربية. ذلك أنه كان لا بد من الدفاع عن أوربا وآسية، ولم يكن الدفاع عنهما مستطاعاً من مدينة في جنوب جبال الألب وتبعد عن تلك الجبال هذا البعد الشاسع. ولهذا أشرك معه في الحكم قائداً محنكاً يدعى مكسميان (286)، وعهد إليه الدفاع عن الغرب؛ ولم يتخذ مكسميان روما عاصمة له بل اتخذ بدلاً منها مدينة ميلان. وبعد ست سنين من ذلك العام اتخذ كلا الأغسطسين Augusyi "قيصراً" ليساعده في أعباء الحكم وليكون خليفة له من بعده. فاختار دبوقليشان جليريوس Galerius واتخذ هذا عاصمته مدينة صرميوم Sirmium وهي متروڤيتسا Mitrovica على نهر الساڤا Save، وعهد إليه حكم ولايات الدانوب؛ وعين مكسميان قنسطنطيوس طلورس Constantius Chlorus (الأصغر) خلفاً له. واتخذ هذا حاضرته مدينة أوغسطا ترڤرورم Augusta Trevirorum (تريف Treves). وتعهد كل أغسطس أن يعتزل الملك بعد عشرين عاماً ليخلفه قيصره؛ وكان من حق هذا القيصر أن يعين هو الآخر "قيصراً" يعاونه ويخلفه. وزوج كل أغسطس ابنته "بقيصره" فأضاف بذلك رابطة الدم إلى رابطة القانون. وكان دقلديانوس يرجو بذلك أن يسد الطريق على حروب الوراثة، وأن يعيد إلى الحكومة استقرارها ودوامها، وسلطانها، وأن تكون الإمبراطوريّة متأهبة لملاقاة الأخطار في أربع نقاط هامة، سواء أكانت هذه الأخطار ناشئة من الثورات الداخلية، أم من الغزو الخارجي. لقد كان تنظيماً باهراً، جمع كل الفضائل إذا استثنينا فضيلتي الوحدة والحرية. فقد انقسمت الملكية، ولكنها كانت ملكية مطلقة، وكان كل قانون يصدره كل حاكم من الحكام الأربعة يصدر باسمهم جميعا، ويطبق في أنحاء الدولة، وكان قرار الحكام يصبح قانوناً ساعة صدوره، من غير حاجة إلى تصديق مجلس الشيوخ في روما. وكان الحكام هم الذين يعينون جميع موظفي الدولة، ومدت أداة بيروقراطية ضخمة فروعها في جميع أنحاء الدولة.

وأراد دقلديانوس أن يزيد من قوة هذا النظم فحول عبادة عبقرية الإمبراطور إلى عبادة شخصه بوصفه تجسيداً لجوبتر، وتواضع لكسمليان فرضي أن يكون هو هرقول؛ وهكذا هبطت الحكمة والقوة من السماء لتعيدا النظام والسلم إلى الأرض، واتخذ دقلديانوس لنفسه تاجاً - عصّابة عريضة مرصعة باللآلئ - وأثواباً من الحرير والذهب؛ وأحذية مرصعة بالحجارة الكريمة، وابتعد عن أعين الناس في قصره، وحتم على زائريه أن يمروا بين صفين من خصيان التشريفات والحجاب وأمناء القصر ذوي الألقاب والرتب، وأن يركعوا ويقبلوا أطراف ثيابه. لقد كان في الحق رجلاً يعرف العالم حق المعرفة. وما من شك في أنه كان يضحك في السر من هذه الخرافات والأشكال ولكن عرشه كان يعوزه ما يخلعه الزمان عليه من شرعية، وكان يأمل أن يدعمه وأن يقمع اضطراب العامة وعصيان الجيش بأن يخلع على نفسه مظاهر الألوهية والرهبة. وفي ذلك يقول أورليوس فكتور: "واتخذ لنفسه لقب السيد Dominus، ولكنه كان يسير في الناس سيرة الأب"(40) وكان معنى إقامة هذا الطراز الشرقي من الحكم الاستبدادي على يد ابن عبد رقيق، وهذا الجمع بين الإله والملك في شخص واحد، كان معنى هذا عجز الأنظمة الجمهورية في العهود القديمة، والتخلي عن ثمار معركة مرثون، والعودة إلى مظاهر بلاط الملوك الأخمينيين، والمصريين، والبطالمة، والبارثيين، والملوك الساسانيين، وإلى النظريات التي كان يقوم عليها حكم هؤلاء الملوك كما عاد الاسكندر إليها من قبل. ومن هذه الملكية الشرقية الصبغة جاء نظام الملكيات البيزنطية والأوربية، وهو النظام الذي طل قائماً إلى أيام الثورة الفرنسية. ولم يبقَ بعد هذا إلا أن يتحالف الملك الشرقي في عاصمة شرقية مع دين شرقي. ولقد بدأت الخواص البيزنطية في الظهور أيام دقلديانوس.

| الأبرشية | الأقاليم |

|---|---|

| الشرق | |

| أوريينس | ليبيا، مصر، فلسطين، سوريا, وقيليقيا |

| پنطس | قپادوقيا، أرمنيا الصغرى, Galatia, بيثينيا |

| آسيا (آسيانا) | آسيا, فريگيا، Pisidia, لوقيا، ليديا، كاريا |

| تراقيا | موئسيا السفلى، تراقيا |

| موئسيا | موئسيا السفلى، داتشيا، إپيروس، مقدونيا، تساليا، |

| الغرب | |

| أفريكا | Africa Proconsularis, Byzacena, Tripolitana, نوميديا، جزء من |

| هسپانيا | Mauretania Tingitana, Baetica, Lusitania,

Tarraconensis |

| Prov. Viennensis | نربوننسس، أكيتانيا، Viennensis, الألپ البحرية |

| غاليا | Lugdunensis، جرمانيا العليا، جرمانيا السفلى، بلجيكا |

| بريطانيا | بريطانيا, Caesariensis |

| Italia | Venetia et Histria, Aemilia et Liguria, Flaminia et Picenum, Raetia, Alpes Cottiae, Tuscia et Umbria, Valeria, Campania et Samnium, Apulia et Calabria, Sicilia, Sardinia et Corsica |

| پانونيا | Pannonia Inferior, Pannonia Superior, Noricum, |

وسار دقلديانوس في عمله بنشاط لا يقل عن نشاط قيصر، فأخذ يعيد تنظيم كل فرع من فروع الإدارة الحكومية. وبدل أحوال الأشراف بأن رفع إلى طبقتهم كثيرين من الموظفين المدنيين أو العسكريين، وبأن جعلها طبقة وراثية ذات مراتب مختلفة على النظام الشرقي، وألقاب كثيرة، ومراسم معقدة متعددة. وقسم هو وزملاؤه الإمبراطوريّة إلى ست وتسعين ولاية تتألف منها اثنتان وسبعون أبرشية، وأربع مقاطعات، وعين لكل قسم حاكم مدني وآخر عسكري، وأصبحت الدولة بذلك ذات حكومة مركزية صريحة، ترى أن الاستقلال الذاتي المحلي، وأن الديمقراطية نفسها، ترف لا يصلح إلا لأوقات الأمن والسلم، وتبرر سلطانها المطلق بحاجات الحرب القائمة أو المتوقعة. ودارت رحى الحرب في تلك الأيام فعلاً وأحرزت الدولة فيها انتصارات باهرة؛ فاستعاد قنسطنطيوس بريطانيا التي ثارت عليه، وأوقع جليريوس بالفرس هزيمة منكرة حاسمة أسلموا بعدها أرض النهرين وخمس ولايات وراء نهر دجلة، وصد أعداء رومت عن حدودها جيلاً من الزمان.

الحكم الرباعي

وواجه دقلديانوس وأعوانه في زمن السلم المشاكل الناشئة من الانحلال الاقتصادي، فأحل محل قانون العرض والطلب نظاماً اقتصادياً تسيطر عليه الدولة ليتغلب بذلك على الكساد ويمنع نشوب الثورات. ووضع نظاماً نقدياً سليماً بأن عين للعملة الذهبية وزناً وعياراً محددين، احتفظت بهما الإمبراطوريّة الشرقية حتى عام 1453، ووزع الطعام على الفقراء بنص ثمنه في السوق أو بغير ثمن على الإطلاق، وشرع يقيم كثيراً من المنشآت العامة ليوجد بذلك عملاً للمتعطلين، ووضع عدداً كبيراً من فروع الصناعة والتجارة تحت سيطرة الدولة ليضمن بذلك حاجات المُدن والجيش؛ وبدأ هذه السيطرة الكاملة باستيراد الحبوب فأقنع أصحاب السفن والتجار والبحارة المشتغلين بهذه التجارة أن يقبلوا أشراف الدولة عليها نظير ضمان الحكومة لعدم تعطلهم ولأرباحهم. وكانت الدولة من زمن قديم تمتلك معظم مقالع الحجارة، ورواسب الملح، والمناجم، ولكنها خطت في ذلك الوقت خطوة أخرى فحرمت تصدير الملح، والحديد، والذهب، والخمر، والحبوب، والزيت، من إيطاليا، وفرضت نظاماً دقيقاً صارماً على استيراد هذه المواد. ثم انتقلت بعد ذلك إلى السيطرة على المؤسسات الصناعية التي تنتج حاجيات الجيش، وموظفي الدولة وبلاط الأباطرة، وحتمت على مصانع الذخيرة، والنسيج، والمخابز ألا يقل إنتاجها عن قدر معين، واشترت هذا القدر بالأثمان التي حددتها هي له، وألقت على جمعيات الصناع تبعات تنفيذ أوامرها ومواصفات منتجاتها، فإذا تبينت أن هذه الخطة لم تؤدِ إلى الغرض المقصود منها أممت هذه المصانع، وجهزتها بعمال فرضت عليهم أن يعملوا فيها. وبهذا وضعت الكثرة الغالبة من المؤسسات الصناعية والنقابات الطائفية في إيطاليا شيئاً فشيئاً تحت سيطرة الدولة المتحدة في عهد أورليان ودقلديانوس. وخضع القصابون والخبازون، والبناءون، وصناع الزجاج، والحديد، والحفارون خضع هؤلاء جميعاً لنظم مفصلة وضعتها لهم الحكومة. ويقول رستوفتزف إن الهيئات الصناعية المختلفة كانت أشبه بمراقبات صغرى على مؤسساتها تقوم بهذا العمل نيابة عن الدولة وكانت أشبه بهذه المراقبات منها بمالكة المؤسسات. وكانت خاضعة لسلطان موظفي المصالح الحكومية المختلفة، ولقواد الوحدات العسكرية المتباينة.

وحصلت جمعيات التجار والصناع من الحكومة على مزايا كثير متنوعة، وكثيراً ما كانت تؤثر تأثيراً كبيراً في خططها؛ وكانت في نظير هذه المزايا وهذا التأثير تعمل كأنها أعضاء في الإدارة القومية، فكانت تساعد الحكومة على وسائل من الإشراف الحكومي شبيهة بهذه الوسائل في القرن الثالث وأوائل القرن الرابع إلى مصانع الأسلحة القائمة في الولايات، وإلى صناعة الأطعمة والملابس. وفي ذلك يقول بول-لوي: "وكان كل ولاية رقيب خاص يشرف على نواحي النشاط الصناعي، وأصبحت الدولة في كل مدينة كبيرة صاحب عمل وذات قوة كبيرة... تسيطر على جميع المصانع الخاصة التي كانت ترزح تحت أعباء الضرائب الفادحة".

ولم يكن مستطاعاً أن يسيطر هذا النظام إلا إذا سيطرت الدولة على أثمان السلع، ولهذا أصدر دقلديانوس وزملاؤه في عام 301 قانون الأثمان الذي حددت به أقل الأثمان والإجور التي يجيزها القانون لجميع السلع أو الخدمات العامة في جميع أنحاء الإمبراطوري. وهاجم القرار في مقدمته الاحتكارات التي منعت البضائع من السوق في الوقت الذي "قلت فيه السلع" لكي ترتفع أثمانها.

"ومَن ذا الذي... خلا قلبه من العاطفة الإنسانية فلا يرى أن ارتفاع الأسعار ظاهرة عامة في أسواق مُدننا، وأن شهوة الكسب لا يحد منها وفرة السلع ولا أعوام الرخاء؟- ولهذا... يرى أشرار الناس أنهم يخسرون إذا ما توافرت الحاجات... إن من الناس مَن يجعلون همهم الوقوف في وجه الرخاء العام... والجري وراء الأرباح الباهظة القاتلة... لقد عم الشره جميع الجشعون الأثمان، ولم يكتفوا بالحصول على سبعة أضعاف الثمن المعتاد أو ثمانية أضعافه، بل زادوه إلى الحد الذي تعجز الألفاظ عن وصفه، حتى لقد يضطر الجندي إلى دفه مرتبه كله وإعانة الحرب في شراء سلعة واحدة، وبذلك يذهب كل ما يقدمه العالم كله لإمداد الجيش بحاجته في جيوب أولئك اللصوص الجشعين .

ولقد ظل هذا المرسوم حتى وقتنا الحاضر أعظم محاولة في التاريخ كله لاستبدال القرارات الحكومية بالقوانين الاقتصادية. ولكن التجربة أخفقت إخفاقاً عاجلاً كاملاً، فقد أخفى التجار ما عندهم من السلع وشحت البضائع أكثر من ذي قبل، واتهم دقلديانوس نفسه بالتغاضي عن ارتفاع الأسعار. وحدثت عدة اضطرابات؛ واضطرت الحكومة إلى التراخي في تطبيق المرسوم لإعادة الإنتاج والتوزيع إلى حالتهما الطبيعية، وانتهى الأمر بإلغائه على يد قسطنطين.

وكانت علة ضعف هذا النظام الاقتصادي الخاضع للسيطرة الحكومية هي ما تطلّبه تنفيذه من نفقات. فقد بلغت البيروقراطية التي تطلّبها تنفيذه من الاتساع درجة وصفها لكتنيوس بأنها احتاجت إلى نصف السكان؛ ولا شك في أنه بالغ في هذا التقدير مبالغة كان الباعث عليها ميوله السياسية، ووجد الموظفون آخر الأمر أن عملهم هذا مما تنوء به العدالة الإنسانية، وكانت رقابتهم متباعدة يستطيع الناس أن يقتلوا منها بما أوتوا من مكر ودهاء. وارتفعت الضرائب ارتفاعاً لم يكن له مثيل من قبل، وفرضت على كل شيء لأداء أجور الموظفين، ونفقات البلاط، والجيش، وبرنامج المنشآت العامة، وإعالة العجزة والمتعطلين، ولكن الدولة قد كشفت بعد طريقة الاستدانة لتخفي بها إسرافها وتؤجل يوم حسابها، فقد كانت أعمال كل عام ينفق عليها من إيراد العام نفسه، وأراد دقلديانوس أن يحتاط لما عساه أن يحدث من أداء الضريبة بعملة مخفضة، فأمر بأن تؤدى الضرائب عيناً كلما كان ذلك مستطاعاً، وحتم على دافعي الضرائب أن يؤدوا ما عليهم إلى مخازن حكومية، ووضع نظاماً شاقاً لنقل هذه الضرائب العينية من هذه المخازن إلى مقرها الأخير، وجعل موظفي البلديات في كل بلدية مسئولين من الوجهة المالية عن كل تقصير في تحصيل الضرائب المفروضة على إقليمهم.

وإذ كان من طبيعة كل ممول أن يحاول الهروب من أداء ما عليه من الضرائب، فقد أنشأت الدولة قوة خاصة من الشرطة للفحص عن أملاك كل شخص ودخله؛ واستخدمت وسائل التعذيب مع الزوجات، والأطفال، والعبيد لإرغامهم على الكشف عن ثروة بيوتهم أو مكاسبها، وفرضت عقوبات صارمة على مَن يحاولون الهرب من أداء ما عليهم. ومع هذا كله فقد كاد الفرار من الضرائب أن يصبح وباء متفشياً في الإمبراطوريّة كلها في القرن الثالث، وأضحى أكثر تفشياً في القرن الرابع؛ فكان الأغنياء يخفون ثروتهم، وبدل الأشراف طبقتهم ووضعوا أنفسهم في عداد الطبقة الدنيا حتى لا يُختاروا للوظائف البلدية، وهجر الصناع حرفهم، وترك الزراع أرضهم المثقلة بالضرائب ليصبحوا أجراء عند غيرهم، وأقفرت كثير من القرى وبعض البلدان الكبيرة (مثل طبرية في فلسطين) من أهلها لفدح الضرائب المفروضة عليها، فلما كان القرن الرابع اجتاز عدد كبير من الأهلين حدود الإمبراطوريّة ولجأوا إلى البرابرة فوراً من الضرائب الفادحة.

وأكبر الظن أن الذي حمل دقلديانوس على الالتجاء إلى تلك الأعمال، التي أوجدت واقع الأمر نظام الاسترقاق الإقطاعي في الحقول، والمصانع، والنقابات الطائفية، هو حرصه على منع هذه الهجرة التي تكلف الدولة كثيراً من النفقة، وعلى ضمان ورود العام بانتظام للجيش والمُدن، والضرائب لبيت المال. وبعد أن جعلت الحكومة مالك الأرض بما فرضته عليه من الضرائب النوعية مسئولاً عن حسن استغلال مزارعيه لأرضه، قررت أن يبقى الزارع في أرضه حتى يؤدي جميع المتأخر عليه من الديون أو العشور. ولسنا نعرف متى صدر هذا القرار التاريخي، ولكنا نعرف أن قسطنطين سن في عام 332 قانوناً يفترض وجود هذا القرار ويؤكده؛ ويجعل المستأجر "يرتبط كتابة" بالأرض التي يزرعها، لا يستطيع تركها إلا برضاء مالكها، فإذا بيعت الأرض بيع هو وأسرته معها(60). وليس فيما وصل إلينا من المعلومات ما يدل على أن الزّراع قد احتجوا على هذه القيود؛ ولعل هذا القانون قد قدّم إليه ضماناً لأمنه وسلامته، كما هو حادث في ألمانيا في هذه الأيام. وبهذه الطريقة وأمثالها انتقلت الزراعة في القرن الثالث من الاسترقاق إلى الحرية ثم الاسترقاق الإقطاعي، وبهذا النظام استقبلت العصور الوسطى.

واتبعت الصناعة وسائل من هذا النوع ليضمن بذلك استقرارها. فحرم على العمال تغيير عملهم، أو الانتقال من مصنع إلى مصنع إلا بموافقة الحكومة؛ وقصرت كل نقابة طائفية على حرفتها والعمل المقرر لها، وحرم على أي إنسان أن يغادر النقابة التي سجل اسمه فيها. وألزم كم مَن يعمل في الصناعة أو التجارة بأن ينضم إلى نقابة من هذه النقابات الطائفية، وحتم على الابن أن يشتغل بحرفة أبيه، فإذا رغب إنسان في أن يستبدل بمكانه أو حرفته مكاناً آخر أو حرفة أخرى ذكرته الدولة بأن إيطاليا يحاصرها البرابرة وأن على كل رجل أو ابن يشتغل بحرفة أن يبقى حيث هو.

النزاعات في البلقان ومصر

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 travelling with Galerius from Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) to Byzantium (Istanbul, Turkey). Diocletian then returned to Sirmium, where he remained for the following winter and spring. He campaigned successfully against the Sarmatians in 294, probably in the autumn.[35] The Sarmatians' defeat kept them from the Danube provinces for a long time. Meanwhile, Diocletian built forts north of the Danube,[36] part of a new defensive line called the Ripa Samartica, at Aquincum (Budapest, Hungary), Bononia (Vidin, Bulgaria), Ulcisia Vetera, Castra Florentium, Intercisa (Dunaújváros, Hungary), and Onagrinum (Begeč, Serbia).[37] In 295 and 296 Diocletian campaigned in the region again, and won a victory over the Carpi in the summer of 296.[38] Later during both 299 and 302, as Diocletian was residing in the East, it was Galerius's turn to campaign victoriously on the Danube. By the end of his reign, Diocletian had secured the entire length of the Danube, provided it with forts, bridgeheads, highways, and walled towns, and sent fifteen or more legions to patrol the region; an inscription at Sexaginta Prista on the Lower Danube extolled restored tranquility to the region.[39] The defense came at a heavy cost but was a significant achievement in an area difficult to defend.[40]

Galerius, meanwhile, was engaged during 291–293 in disputes in Upper Egypt, where he suppressed a regional uprising.[39] He returned to Syria in 295 to fight the revanchist Persian empire.[41] Diocletian's attempts to bring the Egyptian tax system in line with Imperial standards stirred discontent, and a revolt swept the region after Galerius's departure.[42] The usurper Domitius Domitianus declared himself Augustus in July or August 297. Much of Egypt, including Alexandria, recognized his rule.[41] Diocletian moved into Egypt to suppress him, first putting down rebels in the Thebaid in the autumn of 297,[35] then moving on to besiege Alexandria. Domitianus died in December 297,[43] by which time Diocletian had secured control of the Egyptian countryside. Alexandria, whose defense was organized under Domitianus's former corrector Aurelius Achilleus, held out probably until March 298.[41][43]

Bureaucratic affairs were completed during Diocletian's stay:[44] a census took place, and Alexandria, in punishment for its rebellion, lost the ability to mint independently.[45] Diocletian's reforms in the region, combined with those of Septimius Severus, brought Egyptian administrative practices much closer to Roman standards.[46] Diocletian travelled south along the Nile the following summer, where he visited Oxyrhynchus and Elephantine.[45] In Nubia, he made peace with the Nobatae and Blemmyes tribes. Under the terms of the peace treaty Rome's borders moved north to Philae and the two tribes received an annual gold stipend. Diocletian left Africa quickly after the treaty, moving from Upper Egypt in September 298 to Syria in February 299. He met with Galerius in Mesopotamia.[47]

الحرب مع فارس

الغزو والغزو المضاد

In 294, Narseh, a son of Shapur who had been passed over for the Sassanid succession, came to power in Persia.[48] In early 294, Narseh sent Diocletian the customary package of gifts between the empires, and Diocletian responded with an exchange of ambassadors. Within Persia, Narseh was destroying every trace of his immediate predecessors from public monuments. He sought to identify himself with the warlike kings Ardashir I (r. 226–41) and Shapur I (r. 241–72), who had defeated and imprisoned Emperor Valerian (r. 253–260) following his failed invasion of the Sasanian Empire.[49]

Narseh declared war on Rome in 295 or 296. He appears to have first invaded western Armenia, where he seized the lands delivered to Tiridates in the peace of 287.[50][51] He moved south into Roman Mesopotamia in 297, where he inflicted a severe defeat on Galerius in the region between Carrhae (Harran, Turkey) and Callinicum (Raqqa, Syria). The historian Fergus Millar notes, probably somewhere on the Balikh River).[52] Diocletian may or may not have been present at the battle,[53] but he quickly divested himself of all responsibility. In a public ceremony at Antioch, the official version of events was clear: Galerius was responsible for the defeat; Diocletian was not. Diocletian publicly humiliated Galerius, forcing him to walk for a mile at the head of the Imperial caravan, still clad in the purple robes of the Emperor.[54][55][Note 3]

Galerius was reinforced, probably in the spring of 298, by a new contingent collected from the empire's Danubian holdings.[58] Narseh did not advance from Armenia and Mesopotamia, leaving Galerius to lead the offensive in 298 with an attack on northern Mesopotamia via Armenia.[59][Note 4] It is unclear if Diocletian was present to assist the campaign; he might have returned to Egypt or Syria.[Note 5] Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius's force, to Narseh's disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry. In two battles, Galerius won major victories over Narseh. During the second encounter, Roman forces seized Narseh's camp, his treasury, his harem, and his wife.[63] Galerius continued down the Tigris, and took the Persian capital Ctesiphon before returning to Roman territory along the Euphrates.[64]

مفاوضات السلام

Narseh sent an ambassador to Galerius to plead for the return of his wives and children in the course of the war, but Galerius dismissed him.[66] Serious peace negotiations began in the spring of 299. The magister memoriae (secretary) of Diocletian and Galerius, Sicorius Probus, was sent to Narseh to present terms.[66] The conditions of the resulting Peace of Nisibis were heavy:[67] Armenia returned to Roman domination, with the fort of Ziatha as its border; Caucasian Iberia would pay allegiance to Rome under a Roman appointee; Nisibis, now under Roman rule, would become the sole conduit for trade between Persia and Rome; and Rome would exercise control over the five satrapies between the Tigris and Armenia: Ingilene, Sophanene (Sophene), Arzanene (Aghdznik), Corduene (Carduene), and Zabdicene (near modern Hakkâri, Turkey). These regions included the passage of the Tigris through the Anti-Taurus range; the Bitlis pass, the quickest southerly route into Persian Armenia; and access to the Tur Abdin plateau.[68]

A stretch of land containing the later strategic strongholds of Amida (Diyarbakır, Turkey) and Bezabde came under firm Roman military occupation.[69] With these territories, Rome would have an advance station north of Ctesiphon, and would be able to slow any future advance of Persian forces through the region.[67] Many cities east of the Tigris came under Roman control, including Tigranokert, Saird, Martyropolis, Balalesa, Moxos, Daudia, and Arzan – though under what status is unclear.[69] At the conclusion of the peace, Tiridates regained both his throne and the entirety of his ancestral claim.[66] Rome secured a wide zone of cultural influence, which led to a wide diffusion of Syriac Christianity from a center at Nisibis in later decades, and the eventual Christianization of Armenia.[67]

To strengthen the defence of the east Diocletian had a fortified road constructed at the southern border, where the empire bordered the Arabs, in the year 300. This road would remain in use for centuries but proved ineffective in defending the border as conventional armies could not operate in the region.[70]

الاضطهادات الدينية

حرص دقلديانوس معظم سنوات حكمه على اتباع سياسة تسامح دينى مع المسيحيين ، ثم تحولت سياسته ضد المسيحيين في اواخر حكمه ، فاصدر دقلديانوس اربعة مراسيم فيما بين سنتى 302-305 م تحث على اضهاد المسيحيين ، و قد شهدت هذه المراسيم حرق الاناجيل و الكتب الدينية و منع المسيحيين من التجمع و تحريم القيام باى صلوات او طقوس دينية ، و قتل كل الرجال و النساء و الاولاد الذين يرفضون تقديم القرابين للالة الوثنية .

أصدر في مارس عام 303م منشورين متلاحقين بسجن رؤساء الكنائس وتعذيبهم بقصد إجبارهم علي ترك الإيمان .

كان وقع الاضطهاد شديدا على الاقباط في مصر لدرجة انهم اتخذوا من سنة 284 م و هو تاريخ تولية دقلديانوس الحكم بداية للتقويم القبطى[71]

السنوات اللاحقة

مرضه وتنازله عن العرش

ولما استهل عام 305 نزل دقلديانوس ومكسيميان عن سلطتهما باحتفالين مهيبين أقيما في نيقوميديا وميلانو، وأصبح جالريوس، وقنسطنطيوس أغسطسين إمبراطورين أولهما للشرق وثانيهما للغرب. ولم يكن دقلديانوس قد تجاوز وقتئذ الخامسة والخمسين من عمره، ولكنه اختفى في قصره الواسع القائم في سپليت، وقضى فيه الثمانية الأعوام الباقية من حياته. وشهد بعينيه انهيار حكومته الرباعية في غمار الحرب الأهلية. ولما أن ألحّ عليه مكسميان أن يستولي على أزمة الحكم مرة أخرى، ويقضي على الشقاق والحب، قال إنه لو رأى مكسميان الكرنب الجيد الذي يزرعه في حديقته لما طلب إليه أن يضحي بهذه المتعة جرياً وراء متاعب السلطان.

والحق أنه كان قميناً بكرنبه وراحته، فقد قضى على الفوضى التي دامت خمسين عاماً وأقر من جديد سلطان الحكومة والقانون، أعاد الاستقرار إلى الصناعة، ورد الأمن إلى التجارة، وأذل فارس، وخضد شوكة البرابرة، وكان بوجه عام مشترعاً أميناً مخلصاً، وحاكماً عادلاً إذا ضربنا صفحاً عن بحض الاغتيالات القليلة التي جرت على يديه.

ولسنا ننكر أنه أقام بيروقراطية باهظة الأكلاف، وقضى على الاستقلال الذاتي للولايات، وعاقب معارضيه أشد العقاب، واضطهد الكنيسة التي كان في وسعه أن يتخذها حليفة له فيما بذل من الجهود لإصلاح أحوال الدولة، وجعل سكان الإمبراطوريّة مجتمعاً من الطبقات، في أحد طرفيه زرّاع جهلاء وفي طرفه الآخر ملك مستبد مطلق السلطان، ولكن الظروف التي واجهتها روما لم تكن تسمح بانتهاج سياسة تقوم على مبادئ الحرية؛ وقد جرب ماركس أورليوس والكسندر سفيرس هذه السياسة وأخفقا فيها، ورأت الدولة الرومانية نفسها محاطة بالأعداء من كل جانب، ففعلت ما لابد أن تفعله الأمم جميعها في أوقات الحروب التي يتقرر فيها مصيرها، وقبلت طغيان زعيم قوي، ورضيت أن يفرض عليها ما لا تكاد تطيقه من الضرائب، وتخلت عن الحرية الفردية إلى أن تنال الحرية الجماعية، ولقد قام دقلديانوس بالأعمال التي قام بها أغسطس، وإن كانت قد كلفت أولهما أكثر مما كلفت الآخر، ولكنه والحق يقال قام بها في ظروف أقسى من ظروفه، وقد أدرك معاصروه ومَن جاءوا بعده الأخطار التي نجوا منها بفضل جهوده فلقبوه "أبا العصر الذهبي"، وسكن قسطنطين البيت الذي شاده له دقلديانوس.

فى أول مايو سنة 305م تنازل دقليديانوس عن العرش هو ومكسيميان، أي بعد سنتين من تاريخ إصدار أول أوامره .[72]

تربي قسطنطين في بلاط دقلديانوس وهرب إلي بريطانيا وهناك نودي به إمبراطورا علي گاليا وإسبانيا وبريطانيا في عام 306م خلفا لوالده. عبر جبال الألب وانتصر علي منافسه مكسنتيوس بن مكسيميانوس شريك دقلديانوس في حكم الغرب عند قنطرة ملفيا علي بعد ميل واحد من روما، وباد هذا الطاغية هو وجيشه في مياه نهر التيبر في أكتوبر عام 312م . [73]

التقاعد والوفاة

Diocletian retired to his homeland, Dalmatia. He moved into the expansive Diocletian's Palace, a heavily fortified compound located by the small town of Spalatum on the shores of the Adriatic Sea, and near the large provincial administrative center of Salona. The palace is preserved in great part to this day and forms the historic core of Split, the second-largest city of modern Croatia.

Maximian retired to villas in Campania or Lucania. Their homes were distant from political life, but Diocletian and Maximian were close enough to remain in regular contact with each other.[74] Galerius assumed the consular fasces in 308 with Diocletian as his colleague. In the autumn of 308, Galerius again conferred with Diocletian at Carnuntum (Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria). Diocletian and Maximian were both present on 11 November 308, to see Galerius appoint Licinius to be Augustus in place of Severus, who had died at the hands of Maxentius. He ordered Maximian, who had attempted to return to power after his retirement, to step down permanently. At Carnuntum people begged Diocletian to return to the throne, to resolve the conflicts that had arisen through Constantine's rise to power and Maxentius's usurpation.[75] Diocletian's reply: "If you could show the cabbage that I planted with my own hands to your emperor, he definitely wouldn't dare suggest that I replace the peace and happiness of this place with the storms of a never-satisfied greed."[76]

Diocletian lived for four more years, spending his days in his palace gardens. He saw his tetrarchic system fail, torn by the civil wars of his successors. He heard of Maximian's third claim to the throne, his forced suicide, and his damnatio memoriae. In his own palace, statues and portraits of his former companion emperor were torn down and destroyed. After an illness, Diocletian died on 3 December 311, with some proposing that he took his own life in despair.[77][78][Note 6]

الإصلاحات

الحكم الرباعي والأيديولوجيا

Diocletian saw his work as that of a restorer, a figure of authority whose duty it was to return the empire to peace, to recreate stability and justice where barbarian hordes had destroyed it.[79] He arrogated, regimented and centralized political authority on a massive scale. In his policies, he enforced an Imperial system of values on diverse and often unreceptive provincial audiences.[80] In the Imperial propaganda from the period, recent history was perverted and minimized in the service of the theme of the tetrarchs as "restorers". Aurelian's achievements were ignored, the revolt of Carausius was backdated to the reign of Gallienus, and it was implied that the tetrarchs engineered Aurelian's defeat of the Palmyrenes; the period between Gallienus and Diocletian was effectively erased. The history of the empire before the tetrarchy was portrayed as a time of civil war, savage despotism, and imperial collapse. In those inscriptions that bear their names, Diocletian, the "founder of eternal peace", and his companions are referred to as "restorers of the whole world", men who succeeded in "defeating the nations of the barbarians, and confirming the tranquility of their world". The theme of restoration was conjoined to an emphasis on the uniqueness and accomplishments of the tetrarchs themselves.[81]

The cities where emperors lived frequently in this period – Milan, Trier, Arles, Sirmium, Serdica, Thessaloniki, Nicomedia and Antioch – were treated as alternate imperial seats, to the exclusion of Rome and its senatorial elite.[82] A new style of ceremony was developed, emphasizing the distinction of the emperor from all other persons. The quasi-republican ideals of Augustus's primus inter pares were abandoned for all but the tetrarchs themselves. Diocletian took to wearing a gold crown and jewels, and forbade the use of purple cloth to all but the emperors.[83] His subjects were required to prostrate themselves in his presence (adoratio); the most fortunate were allowed the privilege of kissing the hem of his robe (proskynesis, προσκύνησις).[84] Circuses and basilicas were designed to keep the face of the emperor perpetually in view, and always in a seat of authority. The emperor became a figure of transcendent authority, a man beyond the grip of the masses.[85] His every appearance was stage-managed.[86] This style of presentation was not new – many of its elements were first seen in the reigns of Aurelian and Severus – but it was only under the tetrarchs that it was refined into an explicit system.[87]

الاصلاحات الإدارية

In keeping with his move from an ideology of republicanism to one of autocracy, Diocletian's council of advisers, his consilium, differed from those of earlier emperors. He destroyed the Augustan illusion of imperial government as a cooperative affair among emperor, army, and senate.[86] In its place he established an effectively autocratic structure, a shift later epitomized in the institution's name: it would be called a consistorium, not a council.[88][Note 7] Diocletian regulated his court by distinguishing separate departments (scrinia) for different tasks.[90] From this structure came the offices of different magistri, like the magister officiorum ("Master of Offices"), and associated secretariats. These were men suited to dealing with petitions, requests, correspondence, legal affairs, and foreign embassies. Within his court Diocletian maintained a permanent body of legal advisers, men with significant influence on his re-ordering of juridical affairs. There were also two finance ministers, dealing with the separate bodies of the public treasury and the private domains of the emperor, and the praetorian prefect, the most significant person of the whole. Diocletian's reduction of the Praetorian Guards to the level of a simple city garrison for Rome lessened the military powers of the prefect – although a prefect like Asclepiodotus was still a trained general – but the office retained much civil authority. The prefect kept a staff of hundreds and managed affairs in all segments of government: in taxation, administration, jurisprudence, and minor military commands, the praetorian prefect was often second only to the emperor himself.[91]

Altogether, Diocletian greatly increased the number of bureaucrats at the government's command; Lactantius claimed that there were now more men using tax money than there were paying it.[92] The historian Warren Treadgold estimates that under Diocletian the number of men in the civil service doubled from 15,000 to 30,000.[93] The classicist Roger S. Bagnall estimates that there was one bureaucrat for every 5–10,000 people in Egypt based on 400 or 800 bureaucrats for 4 million inhabitants[94] (no one knows the population of the province in 300 AD; Strabo, 300 years earlier, put it at 7.5 million, excluding Alexandria). (By comparison, the ratio in 12th-century Song dynasty China was one bureaucrat for every 15,000 people.)[95] Jones estimated 30,000 bureaucrats[96] for an empire of 50–65 million inhabitants, which works out to approximately 1,667 or 2,167 inhabitants per imperial official as averaged empire-wide. The actual numbers of officials and ratios per inhabitant varied by diocese depending on the number of provinces and population within a diocese. Provincial and diocesan paid officials (there were unpaid supernumeraries) numbered about 13–15,000 based on their staff establishments as set by law. The other 50% were with the emperor(s) in his or their comitatus, with the praetorian prefects, or with the grain supply officials in the capital (later, the capitals, Rome and Constantinople), Alexandria, and Carthage and officials from the central offices located in the provinces.[citation needed]

To avoid the possibility of local usurpations,[97] to facilitate a more efficient collection of taxes and supplies, and to ease the enforcement of the law, Diocletian doubled the number of provinces from fifty to almost one hundred.[98] The provinces were grouped into twelve dioceses, each governed by an appointed official called a vicarius, or "deputy of the praetorian prefects".[99] Some of the provincial divisions required revision, and were modified either soon after 293 or early in the fourth century.[100] Rome herself (including her environs, as defined by a 100-ميل (160 km)-radius perimeter around the city itself) was not under the authority of the praetorian prefect, as she was to be administered by a city prefect of senatorial rank – the sole prestigious post with actual power reserved exclusively for senators, except for some governors in Italy with the titles of corrector and the proconsuls of Asia and Africa.[101]

The dissemination of imperial law to the provinces was facilitated by Diocletian's reform of the Empire's provincial structure, which meant that there were now more governors (praesides) ruling over smaller regions and smaller populations.[102] Diocletian's reforms shifted the governors' main function to that of the presiding official in the lower courts:[103] whereas in the early Empire military and judicial functions were the function of the governor, and procurators had supervised taxation, under the new system vicarii and governors were responsible for justice and taxation, and a new class of duces ("dukes"), acting independently of the civil service, had military command.[104] These dukes sometimes administered two or three of the new provinces created by Diocletian, and had forces ranging from two thousand to more than twenty thousand men.[105] In addition to their roles as judges and tax collectors, governors were expected to maintain the postal service (cursus publicus) and ensure that town councils fulfilled their duties.[106]

This curtailment of governors' powers as the Emperors' representatives may have lessened the political dangers of an all-too-powerful class of Imperial delegates, but it also severely limited governors' ability to oppose local landed elites, especially those of senatorial status, which, although with reduced opportunities for office holding, retained wealth, social prestige, and personal connections,[107] particularly in relatively peaceful regions without a great military presence.[108] On one occasion, Diocletian had to exhort a proconsul of Africa not to fear the consequences of treading on the toes of the local magnates of senatorial rank.[109] If a governor of senatorial rank himself felt these pressures, the difficulties faced by a mere praeses were likely greater.[97] This led to a strained relationship between the central power and local elites: sometime during 303, attempted military sedition in Seleucia Pieria and Antioch prompted Diocletian to extract bloody retribution on both cities by putting to death a number of their council members for failing in their duties of keeping order in their jurisdiction.[110]

الاصلاحات القضائية

As with most emperors, much of Diocletian's daily routine rotated around legal affairs – responding to appeals and petitions, and delivering decisions on disputed matters. Rescripts, authoritative interpretations issued by the emperor in response to demands from disputants in both public and private cases, were a common duty of second- and third-century emperors. In the "nomadic" imperial courts of the later Empire, one can track the progress of the imperial retinue through the locations from whence particular rescripts were issued – the presence of the Emperor was what allowed the system to function.[111] Whenever the imperial court would settle in one of the capitals, there was a glut in petitions, as in late 294 in Nicomedia, where Diocletian kept winter quarters.[112]

Admittedly, Diocletian's praetorian prefects – Afranius Hannibalianus, Julius Asclepiodotus, and Aurelius Hermogenianus – aided in regulating the flow and presentation of such paperwork, but the deep legalism of Roman culture kept the workload heavy.[113] Emperors in the forty years preceding Diocletian's reign had not managed these duties so effectively, and their output in attested rescripts is low. Diocletian, by contrast, was prodigious in his affairs: there are around 1,200 rescripts in his name still surviving, and these probably represent only a small portion of the total issue.[114] The sharp increase in the number of edicts and rescripts produced under Diocletian's rule has been read as evidence of an ongoing effort to realign the whole Empire on terms dictated by the imperial center.[115]

Under the governance of the jurists Gregorius, Aurelius Arcadius Charisius, and Hermogenianus, the imperial government began issuing official books of precedent, collecting and listing all the rescripts that had been issued since the reign of Hadrian (r. 117–38).[116] The Codex Gregorianus includes rescripts up to 292, which the Codex Hermogenianus updated with a comprehensive collection of rescripts issued by Diocletian in 293 and 294.[100] Although the very act of codification was a radical innovation, given the precedent-based design of the Roman legal system,[117] the jurists were generally conservative, and constantly looked to past Roman practice and theory for guidance.[118] They were probably given more free rein over their codes than the later compilers of the Codex Theodosianus (438) and Codex Justinianus (529) would have. Gregorius and Hermogenianus's codices lack the rigid structuring of later codes,[119] and were not published in the name of the emperor, but in the names of their compilers.[120] Their official character, however, was clear in that both collections were subsequently acknowledged by courts as authoritative records of imperial legislation up to the date of their publication and regularly updated.[121]

After Diocletian's reform of the provinces, governors were called iudex, or judge. The governor became responsible for his decisions first to his immediate superiors, as well as to the more distant office of the emperor.[122] It was most likely at this time that judicial records became verbatim accounts of what was said in trial, making it easier to determine bias or improper conduct on the part of the governor. With these records and the Empire's universal right of appeal, Imperial authorities probably had a great deal of power to enforce behavior standards for their judges.[123] In spite of Diocletian's attempts at reform, the provincial restructuring was far from clear, especially when citizens appealed the decisions of their governors. Proconsuls, for example, were often both judges of first instance and appeal, and the governors of some provinces took appellant cases from their neighbors. It soon became impossible to avoid taking some cases to the emperor for arbitration and judgment.[124] Diocletian's reign marks the end of the classical period of Roman law. Where Diocletian's system of rescripts shows adherence to classical tradition, Constantine's law is full of Greek and eastern influences.[125]

الإصلاحات العسكرية

It is archaeologically difficult to distinguish Diocletian's fortifications from those of his successors and predecessors. The Devil's Dykes, for example—the Danubian earthworks traditionally attributed to Diocletian—cannot even be securely dated to a particular century. The most that can be said about built structures under Diocletian's reign is that he rebuilt and strengthened forts at the Upper Rhine frontier (where he followed the works built under Probus along the Lake Constance-Basel and the Rhine–Iller–Danube line),[126] on the Danube (where a new line of forts on the far side of the river, the Ripa Sarmatica, was added to older, rehabilitated fortresses),[127] in Egypt and on the frontier with Persia. Beyond that, much discussion is speculative and reliant on the broad generalizations of written sources. Diocletian and the tetrarchs had no consistent plan for frontier advancement, and records of raids and forts built across the frontier are likely to indicate only temporary claims. The Strata Diocletiana, built after the Persian Wars, which ran from the Euphrates North of Palmyra and South towards northeast Arabia in the general vicinity of Bostra, is the classic Diocletianic frontier system, consisting of an outer road followed by tightly spaced forts – defensible hard-points manned by small garrisons – followed by further fortifications in the rear.[127][128] In an attempt to resolve the difficulty and slowness of transmitting orders to the frontier, the new capitals of the tetrarchic era were all much closer to the empire's frontiers than Rome had been:[129] Trier sat on the Moselle, a tributary of the Rhine, Sirmium and Serdica were close to the Danube, Thessaloniki was on the route leading eastward, and Nicomedia and Antioch were important points in dealings with Persia.[130]

Lactantius criticized Diocletian for an excessive increase in troop sizes, declaring that "each of the four princes strove to maintain a much more considerable military force than any sole emperor had done in times past. There began to be fewer men who paid taxes than there were who received wages; so that the means of the husbandmen being exhausted by enormous impositions, the farms were abandoned, cultivated grounds became woodland, and universal dismay prevailed".[92] The fifth-century pagan Zosimus, by contrast, praised Diocletian for keeping troops on the borders, rather than keeping them in the cities, as Constantine was held to have done.[131] Both these views had some truth to them, despite the biases of their authors: Diocletian and the tetrarchs did greatly expand the army, and the growth was mostly in frontier regions, where the increased effectiveness of the new Diocletianic legions seem to have been mostly spread across a network of strongholds.[132] Nevertheless, it is difficult to establish the precise details of these shifts given the weakness of the sources.[133][93] The army expanded to about 580,000 men from a 285 strength of 390,000, of which 310,000 men were stationed in the East, most of whom manned the Persian frontier. The navy increased from approximately 45,000 to approximately 65,000 men.[93][Note 8]

Diocletian's expansion of the army and civil service meant that the empire's tax burden grew. Since military upkeep took the largest portion of the imperial budget, any reforms here would be especially costly. The proportion of the adult male population, excluding slaves, serving in the army increased from roughly 1 in 25 to 1 in 15, an increase judged excessive by some modern commentators. Official troop allowances were kept to low levels, and the mass of troops often resorted to extortion or the taking of civilian jobs. Arrears became the norm for most troops. Many were even given payment in kind in place of their salaries. Were he unable to pay for his enlarged army, there would likely be civil conflict, potentially open revolt. Diocletian was led to devise a new system of taxation.[136]

الاصلاحات الاقتصادية

الضرائب

In the early empire (30 BC – AD 235) the Roman government paid for what it needed in gold and silver. The coinage was stable. Requisition, forced purchase, was used to supply armies on the march. During the third-century crisis (235–285), the government resorted to requisition rather than payment in debased coinage, since it could never be sure of the value of money. Requisition was nothing more or less than seizure. Diocletian made requisition into tax. He introduced an extensive new tax system based on heads (capita) and land (iugera) – with one iugerum equal to approximately 0.65 acres – and tied to a new, regular census of the empire's population and wealth. Census officials traveled throughout the empire, assessed the value of labor and land for each landowner, and joined the landowners' totals together to make citywide totals of capita and iuga.[137] The iugum was not a consistent measure of land, but varied according to the type of land and crop, and the amount of labor necessary for sustenance. The caput was not consistent either: women, for instance, were often valued at half a caput, and sometimes at other values.[138] Cities provided animals, money, and manpower in proportion to its capita, and grain in proportion to its iuga.[137][Note 9]

Most taxes were due each year on 1 September, and levied from individual landowners by decuriones (decurions). These decurions, analogous to city councilors, were responsible for paying from their own pocket what they failed to collect.[140] Diocletian's reforms also increased the number of financial officials in the provinces: more rationales and magistri privatae are attested under Diocletian's reign than before. These officials represented the interests of the fisc, which collected taxes in gold, and the Imperial properties.[100] Fluctuations in the value of the currency made collection of taxes in kind the norm, although these could be converted into coin. Rates shifted to take inflation into account.[137] In 296, Diocletian issued an edict reforming census procedures. This edict introduced a general five-year census for the whole empire, replacing prior censuses that had operated at different speeds throughout the empire. The new censuses would keep up with changes in the values of capita and iuga.[141]

Italy, which had long been exempt from taxes, was included in the tax system from 290/291 as a diocesis.[142] The city of Rome remained exempt; the "regions" (i.e., provinces) South of Rome (generally called "suburbicarian", as opposed to the Northern, "annonaria" region) seem to have been relatively less taxed, in what probably was a sop offered to the great senatorial families and their landed properties.[143]

Diocletian's edicts emphasized the common liability of all taxpayers. Public records of all taxes were made public.[144] The position of decurion, member of the city council, had been an honor sought by wealthy aristocrats and the middle classes who displayed their wealth by paying for city amenities and public works. Decurions were made liable for any shortfall in the amount of tax collected. Many tried to find ways to escape the obligation.[140] By 300, civilians across the empire complained that there were more tax collectors than there were people to pay taxes.[145]

العملة والتضخم

تظل أبرز حلقات التحكم فى الأسعار في تاريخ روما القديم، هى التى تمت فى عهد الإمبراطور دقلديانوس (244م-312م) الذي تولى عرش روما عام 284 وبدأ على الفور فى زيادة الإنفاق العام على نحو غير مسبوق، من أجل تمويل مشروعات حكومية عظيمة التكاليف.[146]

وفقاً لريتشارد إبلينج ارتفع فى عهد دقلديانوس الإنفاق على تسليح الجيش والإنفاق العسكرى بصفة عامة. كذلك تم البدء فى إقامة عاصمة جديدة للإمبراطورية الرومانية في آسيا الصغرى (تركيا حالياً) فى مدينة نيكوميديا. توسّعت البيروقراطية الرومانية فى عهد دقلديانوس، وتم تسخير العمالة لإنهاء المشروعات الكبرى التي خطط لها. ومن أجل تمويل تلك الأنشطة الحكومية قام الإمبراطور برفع الضرائب على جميع فئات الشعب الرومانى، وقد نتج عن ذلك ما هو متوقع من تراجع الحافز للعمل والإنتاج والادخار والاستثمار، وما نشأ عن ذلك من تدهور حركة التجارة.

وعندما عجزت الضرائب عن تمويل احتياجات الإنفاق العام، لجأ الإمبراطور إلى تخفيض قيمة العملة وكان ذلك يتم تاريخياً عبر مزج المعدن النفيس المكون للعملة (من ذهب وفضة) بمعادن أساسية رخيصة، وتخفيض وزن المعدن النفيس فى العملة الجديدة. ثم أصدرت الحكومة القوانين التي تجبر المواطنين فى روما ومختلف الأصقاع التابعة للإمبراطورية على تقبّل العملة المصدرة حديثاً بنفس قيمة العملة القديمة، بعد سك تلك القيمة كتابة على وجهى العملة. لكن مرة أخرى عجزت الدولة عن فهم السلوك البشري، الذي جنح إلى تقبّل العملة الجديدة في التداول ولكن بقيمة مخفّضة، وسرعان ما ساد قانون طرد العملة الرديئة للعملة الجيدة، حيث لجأ المتعاملون إلى تخزين العملات ذات المكون الأعلى من الذهب والفضة، وسادت العملة الجديدة فى الأسواق، لكن كما سبقت الإشارة لم تعد تشترى نفس القدر من السلع والخدمات بذات الثمن الذي بيعت به مقابل العملات الجيدة، وهذا هو التضخم، الذى استشرى مع لجوء الإمبراطور إلى سك المزيد والمزيد من تلك العملات الرديئة لتمويل الإنفاق العام.

لم يتوقف دقلديانوس عند هذا الحد من العبث بالاقتصاد، فقد فرض ضرائب عينية عوضاً عن الضرائب النقدية، إقراراً منه بأن نقوده الرديئة لا قيمة لها. الأمر الذي تسبب فى شلل حركة الاقتصاد، وربط السكان بالأرض أو بمراكز الإنتاج المباشر للسلع التي تقبلها الدولة لسداد الضرائب! هذا فرض تغيراً هيكلياً على اقتصاد الإمبراطورية، الذى أصبح جامداً متكلساً فضلاً عن العيوب آنفة الذكر.

وفى عام 301م أقدم الإمبراطور على إصدار أسوأ مرسوم فى تاريخ البلاد والمعروف بمرسوم دقلديانوس. فقد قام الإمبراطور بتثبيت أسعار القمح واللحوم والبيض والملابس وعدد من المنتجات الأخرى. كما قام بتثبيت أجور العاملين فى إنتاج تلك السلع، وكانت العقوبة التى أقرها على مخالفة تسعيرته الجبرية هى الموت!! نتيجة لهذا المرسوم المخيف اختفى أى حافز للإنتاج والتجارة فى تلك السلع، والتى يعنى الاستمرار فى إنتاجها وتداولها إما الخسارة (بالبيع تحت القيمة العادلة) أو الموت (لمخالفة التسعيرة الجبرية الظالمة). وقد استبق المرسوم أى محاولة لاحتكار تلك السلع ومنعها من الأسواق (كنتيجة منطقية لرفض التسعيرة الجبرية) بعقوبات المصادرة للسلع والموت أيضا للمحتكر.

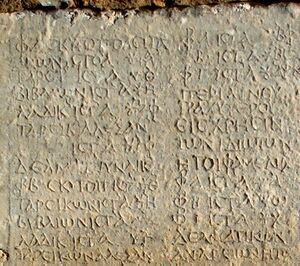

فى الأجزاء اليونانية من الإمبراطورية الرومانية عثر الأثريون على جداول التسعيرة الجبرية لأكثر من ألف صنف من السلع والأجور، التى أقرتها الحكومة وفرضتها على الشعوب الخاضعة لسيطرتها. وقد وجدت مخطوطة لرجل روماني يدعى لاكتانيوس كتب فيها عن دقلديانوس:

يقول المؤرخ الاقتصادي رولاند كنت ملخصاً تلك الحقبة الرومانية تحت حكم دقلديانوس: "إن الحدود السعرية التي فرضها المرسوم لم يعن بها التجار، على الرغم من عقوبة الإعدام التي فرضت على مخالفيها. وكان احتكار السلع يتم بشكل منظم تحاشياً للعقوبات وللعصابات التي شكّلت لمعاقبة التجار المخالفين، وكانت السلع المهرّبة تباع بأثمان أغلى من تلك التي فرضها القانون».

الآثار الاقتصادية لمرسوم دقلديانوس كانت مدمّرة، وبعد أربع سنوات من صدور المرسوم تنحى الإمبراطور عن السلطة بزعم تدهور حالته الصحية، ويرى المحللون أنه إن لم يكن تنحى طواعية لتم عزله بالقوة أو اغتياله كما كان سائداً في هذا الزمان. وعلى الرغم من عدم إلغاء ذلك المرسوم اللعين رسميا حتى يومنا هذا! فإنه سرعان ما صار حبراً على ورق بعد غياب دقلديانوس عن السلطة.

يقول الاقتصادي النمساوى الشهير لودڤيگ فون ميزس: بدأت الإمبراطورية الرومانية تضعف وتتحلل كونها افتقرت إلى فلسفة الحقوق الفردية والأسواق الحرة، تلك الأفكار والإيديولوجية اللازمة لبناء وحماية المجتمع. ويتابع: إن الحضارة الرومانية العظيمة لم تصمد، لأنها لم تضبط بوصلتي نظامها القانوني والأخلاقي على متطلبات اقتصاد السوق. باختصار يرى ميزس أن الدول التي تصدر تشريعات تخالف روح المنافسة والسوق الحرة، وتجرّم السلوك التنافسى عوضا عن تحفيزه وتشجيعه، وتتبنى نسقا أخلاقيا معاديا للطبيعة البشرية، لابد أن تندثر وتسقط مهما كانت حضارتها قوية، ومهما بلغت جيوشها واتسعت رقعة سيطرتها.

كذلك رأى العديد من المؤرخين والاقتصاديين أن دقلديانوس كان لا يؤمن بالقيم الفردية ويتبنى مفهوماً فوقياً للدولة على حساب مصالح الأفراد. وأن تنظيم الأسواق بالكيفية التى فرضها مرسومه يمكن أن ينجح خلال فترات محدودة جداً، وعلى نطاق ضيق للغاية، لكن استدامة هذا النوع من سيطرة الدولة أمر مستحيل، سواءً فى روما القديمة، أو في الاتحاد السوڤيتي العظيم الذى تهاوى لأسباب مماثلة، أو فى أى مكان وزمان.

الحراك الاجتماعي والمهني

Partly in response to economic pressures and in order to protect the vital functions of the state, Diocletian restricted social and professional mobility. Peasants became tied to the land in a way that presaged later systems of land tenure and workers such as bakers, armourers, public entertainers and workers in the mint had their occupations made hereditary.[147] Soldiers' children were also forcibly enrolled, something that followed spontaneous tendencies among the rank-and-file, but also expressed increasing difficulties in recruitment.[132]

ذكراه

انظر أيضاً

- Camp of Diocletian

- Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy (306–324)

- Dioclesian, Henry Purcell's 1690 tragicomic semi-opera, loosely based on the life of the historical Diocletian

- Diocletian Era, used for dating in late antiquity and in the Coptic calendar

- Diocletian window

- Diocletianopolis (disambiguation)

- Dominate

- Pompey's Pillar (column)

- Rags to riches

- 20,000 Martyrs of Nicomedia

الهوامش

- ^ Coins are issued in his name in Cyzicus at some time before the end of 284, but it is impossible to know whether he was still in the public eye by that point.[9][10]

- ^ He initially reigned under the name "Marcus Aurelius Gaius Valerius Diocletianus", but this formula didn't last long. He reverted back to "Gaius Valerius Diocles" after his retirement.[20]

- ^ It is possible that Galerius's position at the head of the caravan was merely the conventional organization of an imperial progression, designed to show a caesar's deference to his augustus, and not an attempt to humiliate him.[56]

- ^ Faustus of Byzantium's history refers to a battle that took place after Galerius set up base at Satala (Sadak, Turkey) in Armenia Minor, when Narseh advanced from his base at Oskha to attack him.[60] Other histories of the period do not note these events.

- ^ Lactantius criticizes Diocletian for his absence from the front,[61] but Southern, dating Diocletian's African campaigns one year earlier than Barnes, places Diocletian on Galerius's southern flank.[62]

- ^ The range of dates proposed for Diocletian's death have stretched from 311 through to 318. Until recently, the date of 3 December 311 has been favoured; however, the absence of Diocletian on Maxentius's "AETERNA MEMORIA" coins could indicate that he was alive through to Maxentius's defeat in October 312. Given that Diocletian had died by the time of Maximin Daia's death in July 313, it has been argued that the correct date of death was 3 December 312.[77]

- ^ The term consistorium was already in use for the room where council meetings took place.[89]

- ^ The 6th-century author John the Lydian provides extraordinarily precise troop numbers: 389,704 in the army and 45,562 in the navy.[134] His precision has polarized modern historians. Some believe that Lydus found these figures in official documents and that they are therefore broadly accurate; others believe that he fabricated them.[135]

- ^ The army recruitment tax was called the praebitio tironum, and conscripted a part of each landowner's tenant farmers (coloni). When a capitulum extended across many farms, farmers provided the funds to compensate the neighbor who had supplied the recruit. Landowners of senatorial rank were able to commute the tax with a payment in gold (the aurum tironicum).[139]

المصادر

الحواشي

Chapters from The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII: The Crisis of Empire are marked with "(CAH)".

- ^ http://www.sis.gov.eg/Ar/History/ruler/080900000000000017.htm

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 36.

- ^ Mommsen, Theodor (1999) [1856]. A History of Rome Under the Emperors. Barbara Demandt, Alexander Demandt, Thomas E. J. Wiedemann. London: Routledge. pp. 346–348. ISBN 978-0-415-20647-1.

Those accounts we do possess stem from outsiders who in fact know nothing.

- ^ Harries, Jill (2012). Imperial Rome AD 284 to 363: The New Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7486-2052-4. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g0b463.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Barnes 1981, p. 4.

- ^ أ ب Southern 2001, p. 133.

- ^ أ ب Leadbetter 2001a.

- ^ Cod. Justinianus, 5.52.2; Leadbetter 2001a; Potter 2005, p. 279.

- ^ Roman Imperial Coinage Vol. 5.2, "Numerian" no. 462

- ^ Potter 2005, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 34.

- ^ Leadbetter 2001a; Odahl 2004, p. 39; Williams 1985, p. 35.

- ^ Eutropius, 9.19; Epit. Caesaribus, 39.1.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Potter 2005, p. 280.

- ^ CAH, p. 68; Williams 1985, pp. 435–436.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 4–5; Odahl 2004, pp. 39–40; Williams 1985, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 4–5; Leadbetter 2001a; Odahl 2004, pp. 39–40; Williams 1985, p. 37.

- ^ Historia Augusta, "Vita Cari" 13.

- ^ Corcoran 2006, p. 39.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnames - ^ Barnes 1981, p. 5; CAH, p. 69; Potter 2005, p. 280; Southern 2001, p. 134.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Barnes 1981, p. 5.

- ^ أ ب Barnes 1981, p. 5; CAH, p. 69; Leadbetter 2001b.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 134–135; Williams 1985, p. 38; Banchich 1997.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 134–135; Williams 1985, p. 38.

- ^ CAH, p. 69; Potter 2005, p. 280.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 5; Odahl 2004, p. 40; Southern 2001, p. 135.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 5; Williams 1985, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 280; Williams 1985, p. 37.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 5; CAH, p. 69; Odahl 2004, p. 40; Williams 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 135; Williams 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Corcoran, "Before Constantine", 40.

- ^ Southern, 140.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBNCE1718 - ^ أ ب Odahl 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 17; Williams 1985.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 76.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 17; Odahl 2004, p. 59; Southern 2001, pp. 149–150.

- ^ أ ب Carrié & Rousselle 1999, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 77.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnes 1981, p. 17.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 17; Southern 2001, pp. 160, 338.

- ^ أ ب DiMaio 1997.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 17–18; Southern 2001, p. 150.

- ^ أ ب Southern 2001, p. 150.

- ^ Harries 1999, p. 173.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 292; Williams 1985, p. 69.

- ^ Williams 1985, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus 23.5.11

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 17; CAH, p. 81; Potter 2005, p. 292; Southern 2001, p. 149.

- ^ Eutropius, 9.24–25; Barnes 1981, p. 17; CAH, p. 81; Millar 1993, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 652.

- ^ Eutropius 9.24–25; Theophanes Confessor, AM 5793.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 17; CAH, p. 81; Potter 2005, pp. 292–293.

- ^ أ ب Rees 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 151.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 18; CAH, p. 81; Millar 1993, p. 178.

- ^ Millar 1993, p. 178; Potter 2005, p. 293.

- ^ CAH, p. 81.

- ^ Lactantius, 9.6.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 151, 335–336.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 18; Potter 2005, p. 293.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 18; Millar 1993, p. 178.

- ^ Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 14; Southern, 151.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnes 1981, p. 18.

- ^ أ ب ت Potter 2005, p. 293.

- ^ Millar 1993, pp. 178–179; Potter 2005, p. 293.

- ^ أ ب Millar 1993, p. 178.

- ^ Heather, P. J. (Peter J.) (2018). Rome Resurgent: War and Empire in the Age of Justinian. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199362745. OCLC 1007044617.

- ^ http://www.al3ez.net/vb/printthread.php?t=6528

- ^ http://www.coptichistory.org/new_page_1179.htm

- ^ http://www.copticchurch.org/ArabicArticles/martyrdom_christianity.htm

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 27; Southern 2001, p. 152.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 31–32; Lenski 2006, p. 65; Odahl 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Epit. Caesaribus, 39.6.

- ^ أ ب Nakamura, Byron J. (July 2003). "When Did Diocletian Die? New Evidence for an Old Problem". Classical Philology. 98 (3): 283–289. doi:10.1086/420722.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 41.

- ^ Potter 2005, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 298.

- ^ Potter 2005, pp. 294–298, quoting CIL 617, 618 & 641.

- ^ Corcoran 2006, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Corcoran 2006, p. 43; Potter 2005, p. 290.

- ^ CAH, pp. 171–172; Corcoran 2006, p. 43; Liebeschuetz 1979, pp. 235–252.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 290.

- ^ أ ب Southern 2001, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 153–154, 163.

- ^ CAH, pp. 171–172; Southern 2001, pp. 162–163; Williams 1985, p. 110.

- ^ CAH, p. 172, citing the Codex Justinianus 9.47.12.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 162–63; Williams 1985, p. 110.

- ^ Williams 1985, pp. 107–110.

- ^ أ ب Lactantius, 7.

- ^ أ ب ت Treadgold 1997, p. 19.

- ^ Bagnall, Roger S. (1993). Egypt in Late Antiquity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-691-06986-7.

- ^ CAH, fn. 6.

- ^ Jones 1964, p. 1057.

- ^ أ ب Carrié & Rousselle 1999, p. 678.

- ^ As taken from the Laterculus Veronensis or Verona List, reproduced in Barnes 1982, chs. 12–13 (with corrections in Barnes, Timothy D. (1996). "Emperors, panegyrics, prefects, provinces and palaces (284–317)". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 9: 532–552, at 548–550. doi:10.1017/S1047759400017037.). See also: Barnes 1981, p. 9; CAH, p. 179; Rees 2004, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Barnes 1981, p. 9; Rees 2004, pp. 25–26.

- ^ أ ب ت Barnes 1981, p. 10.

- ^ Carrié & Rousselle 1999, pp. 655–666.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 296.

- ^ Harries 1999, pp. 53–54; Potter 2005, p. 296.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 107. There were still some governors – like Arpagius, the 298 governor of Britannia Secunda – who still busied themselves with military affairs in strained circumstances.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 9–10; Treadgold 1997, pp. 18–20.

- ^ Rees 2004, p. 25 citing Corcoran, Simon (1996). The Empire of the Tetrarchs: Imperial Pronouncements and Government A.D. 284–324. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 234–253. ISBN 9780198149842.

- ^ Salzman, Michele Renee (2009). The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-674-00641-0.

- ^ Mennen, Inge (2011). Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193–284. Leiden: Brill. p. 77. ISBN 978-90-04-20359-4.

- ^ Cod. Justinianus, 2.13.1.

- ^ Leadbetter, Bill (2009). Galerius and the Will of Diocletian. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 9780415404884; Veyne, Paul (2005). L'Empire Gréco-Romain. Paris: Seuil. p. 64 fn. 208. ISBN 2-02-057798-4.

- ^ Connolly, Serena (2010). Lives behind the Laws: The World of the Codex Hermogenianus. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-253-35401-3.

- ^ Radner, Karen, ed. (2014). State Correspondence in the Ancient World: From New Kingdom Egypt to the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-19-935477-1.

- ^ Williams 1985, pp. 53–54, 142–143.

- ^ CAH, p. 201; Williams 1985, p. 143.

- ^ Potter 2005, pp. 296, 652.

- ^ Harries 1999, pp. 14–15; Potter 2005, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Potter 2005, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Harries 1999, pp. 21, 29–30; Potter 2005, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Harries 1999, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Harries 1999, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Mousourakis, George (2012). Fundamentals of Roman Private Law. Berlin: Springer. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-642-29310-8.

- ^ Harries 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Harries 1999, p. 167.

- ^ Harries 1999, p. 55.

- ^ CAH, p. 207.

- ^ Carrié & Rousselle 1999, p. 166.

- ^ أ ب Edward Luttwak (1979). The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire. Baltimore: JHU Press, ISBN 0-8018-2158-4, p. 176

- ^ CAH, pp. 124–126; Southern 2001, pp. 154–155; Rees 2004, p. 19–20; Williams 1985, pp. 91–101.

- ^ CAH, p. 171; Rees 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Rees 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Corcoran 2006, p. 46; quoting Zosimus, 2.34.

- ^ أ ب Christol & Nony 2003, p. 241.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 157.

- ^ De Mensibus 1.27.

- ^ Rees 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Southern 2001, pp. 158–159; Treadgold 1997, pp. 112–113.

- ^ أ ب ت Treadgold 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 159.

- ^ CAH, p. 173; Rees 2004, p. 18.

- ^ أ ب Southern 2001, p. 160; Treadgold 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Potter 2005, p. 333.

- ^ Barnes 1981, pp. 9, 288; Rees 2004, pp. 28–29; Southern 2001, p. 159.

- ^ Carrié & Rousselle 1999, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 125.

- ^ Brown 1989, p. 25.

- ^ "مرسوم «دقلديانوس»... درس من تاريخ روما". جريدة الشروق المصرية. 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ Lim, Richard (2010). "Late Antiquity". The Edinburgh Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 115.

المراجع

مراجع أساسية

- Codex Justinianeus (translation) 529.

- Epitome de Caesaribus (translation) ca. 395.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Historia Ecclesiastica (Church History) first seven books ca. 300, eighth and ninth book ca. 313, tenth book ca. 315, epilogue ca. 325. Book 8.

- Eutropius, Breviarium ab Urbe Condita (Abbreviated History from the City's Founding) ca. 369. Book 9

- Lactantius, Liber De Mortibus Persecutorum (Book on the Deaths of the Persecutors) c. 313–15.

- XII Panegyrici Latini (Twelve Latin Panegyrics) relevant panegyrics dated 289, 291, 297, 298, and 307.

- Joannes Zonaras, Compendium of History (Επιτομή Ιστορίων) ca. 1200. Compendium extract: Diocletian to the Death of Galerius: 284–311

المراجع الثانوية

- Banchich, Thomas M. "Iulianus (ca. 286–293 A.D.)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (1997). Accessed 8 March 2008.

- Barnes, Timothy D. "Lactantius and Constantine." The Journal of Roman Studies 63 (1973): 29–46.

- Barnes, Timothy D. "Two Senators under Constantine." The Journal of Roman Studies 65 (1975): 40–49.

- Barnes, Timothy D. Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-674-16531-1

- Barnes, Timothy D. The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1982. ISBN 0-7837-2221-4

- Bleckmann, Bruno. "Diocletianus." In Brill's New Pauly, Volume 4, edited by Hubert Cancik and Helmut Schneider, 429–38. Leiden: Brill, 2002. ISBN 90-04-12259-1

- Bowman, Alan, Averil Cameron, and Peter Garnsey, eds. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII: The Crisis of Empire. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-30199-8

- Brown, Peter (1989). The World of Late Antiquity: AD 150–750. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Co. ISBN 978-0-39395-803-4.

- Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-631-22138-7

- Burgess, R.W. "The Date of the Persecution of Christians in the Army". Journal of Theological Studies 47:1 (1996): 157–58.

- Carrié, Jean-Michel & Rousselle, Aline. L'Empire Romain en mutation- des Sévères à Constantin, 192–337. Paris: Seuil, 1999. ISBN 2-02-025819-6

- Corcoran, Simon. The Empire of the Tetrarchs, Imperial Pronouncements and Government AD 284–324. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-814984-0

- Christol, Michel & Nony, Daniel."Rome et son empire".Paris: Hachette, 2003.ISBN 2-01-145542-1

- Corcoran, Simon. "Before Constantine." In The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, edited by Noel Lenski, 35–58. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Hardcover ISBN 0-521-81838-9 Paperback ISBN 0-521-52157-2

- Digeser, Elizabeth DePalma. Lactantius and Rome: The Making of a Christian Empire. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8014-3594-2

- DiMaio, Jr., Michael. "L. Domitius Domitianus and Aurelius Achilleus (ca. 296/297–ca. 297/298)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (1996c). Accessed 8 March 2008.

- Elliott, T. G. The Christianity of Constantine the Great. Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 1996. ISBN 0-940866-59-5

- Elsner, Jas. Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-284201-3

- Gibbon, Edward. Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Chicago, London & Toronto: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1952 (Great Books of the Western World coll.). In two volumes.

- Harries, Jill. Law and Empire in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Hardcover ISBN 0-521-41087-8 Paperback ISBN 0-521-42273-6

- Helgeland, John. "Christians and the Roman Army A.D. 173–337." Church History 43:2 (1974): 149–163, 200.

- Jones, A.H.M. The Later Roman Empire, 284–602: A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1964.

- Leadbetter, William. "Carus (282–283 A.D.)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (2001a). Accessed 16 February 2008.

- Leadbetter, William. "Numerianus (283–284 A.D.)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (2001b). Accessed 16 February 2008.

- Leadbetter, William. "Carinus (283–285 A.D.)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (2001c). Accessed 16 February 2008.

- Lewis, Naphtali, and Meyer Reinhold. Roman Civilization: Volume 2, The Roman Empire. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-231-07133-7

- Liebeschuetz, J. H. W. G. Continuity and Change in Roman Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0-19-814822-4.

- Mackay, Christopher S. "Lactantius and the Succession to Diocletian." Classical Philology 94:2 (1999): 198–209.

- Mathisen, Ralph W. "Diocletian (284–305 A.D.)." De Imperatoribus Romanis (1997). Accessed 16 February 2008.

- Millar, Fergus. The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.–A.D. 337. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993. Hardcover ISBN 0-674-77885-5 Paperback ISBN 0-674-77886-3

- Nakamura, Byron J. "When Did Diocletian Die? New Evidence for an Old Problem." Classical Philology 98:3 (2003): 283–289.

- Odahl, Charles Matson. Constantine and the Christian Empire. New York: Routledge, 2004. Hardcover ISBN 0-415-17485-6 Paperback ISBN 0-415-38655-1

- Potter, David S. The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395. New York: Routledge, 2005. Hardcover ISBN 0-415-10057-7 Paperback ISBN 0-415-10058-5

- Rees, Roger. Layers of Loyalty in Latin Panegyric: AD 289–307. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-924918-0

- Rees, Roger. Diocletian and the Tetrarchy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7486-1661-6

- Rostovtzeff, Michael. The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966. ISBN 978-0-19-814231-7

- Southern, Pat. The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine. New York: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0-415-23944-3

- Tilley, Maureen A. Donatist Martyr Stories: The Church in Conflict in Roman North Africa. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1996.