خط تماس ناگورنو قرةباخ

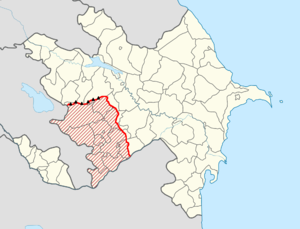

خط التماس (بالأرمينية: շփման գիծ، shp’man gits، آذربيجاني: təmas xətti)، يفصل بين القوات الأرمينية (جيش دفاع ناگورنو قرةباخ) والقوات المسلحة الأذربيجانية في نزاع ناگورنو قرةباخ. تشكل الخط في أعقاب هدنة مايو 1994 التي أنهت حرب ناگورنو قرةباخ (1988–94).[1] تشكل سلسلة جبال موروڤداگ (مراڤ) الجزء الشمالي لخط التماس وهي تمثل الحدود الطبيعية بين القوتين.[2][3] يتراوح طول خط التماس بين 180 [4] و200 كيلومتراً.[5]

المصطلح

يستخدم مصطلح "خط التماس" على نطاق واسع في الوثائق والبيانات الرسمية، بما في ذلك تلك المستخدمة من قبل مجموعة منسك.[6]

يشجع بعض المحللين الأرمن، من بينهم آرا پاپيان، الجانب الأرمني على تجنب استخدام مصطلح "خط التماس"، وإطلاق مصطلح "حدود الدولة" لوصف الحدود بين آرتساخ وأذربيجان.[7][8] ضمن كتاباته، يطلق عليها الصحفي والكاتب المستقل تاتول هاكوبيان عنه باعتباره خدود لدولة أذربيجان وآرتساخ، ويشير إلى أنه يسمى "خط التماس" في القاموس الدولي.[9]

في أذربيجان، عادة ما يشار إلى "خط التماس" باعتباره "خط الاحتلال" بما يتماشى مع اعتبار ناگورنو قرةباخ أرضاً محتلة.[10]

الوصف

كان خط التماس، فور وقف إطلاق النار، "منطقة هادئة نسبياً بها أسلاك شائكة وجنود مسلحون بأسلحة خفيفة يجلسون في خنادق"، بحسب توماس دي وال. كانت هناك أيضاً منطقة آمنة كبيرة نسبياً بعد وقف إطلاق النار والتي كان عرضها عدة كيلومترات في بعض الأماكن. تم تقليصها إلى بضع مئات من الأمتار في معظم مناطق خط التماس بسبب إعادة الانتشار الأذربيجاني في المنطقة المحايدة السابقة.[11]

على النقيض، في عام 2016، كان هناك حوالي 20 ألف رجل على كل جانب من خط التماس المعسكر بكثافة.[12] منذ وقف إطلاق النار، أصبح خط التماس منطقة محرمة وعازلة مسلح ومحصن وملغم بشدة.[1][13][14] حسب دى وال، يعتبر خط التماس "أكثر المناطق عسكرة في أوروپا"،[15] واحد من المناطق الثلاث الأكثر عسكرة في العالم (بجانب كشمير وكوريا).[5] قورنت خنادق خط التماس بنظيراتها في الحرب العالمية الأولى.[5][16][17]

يخضع خط التماس بانتظام لمراقبة مجموعة من ستة أعضاء في منظمة الأمن والتعاون في أوروپا، برئاسة أندريه كاسپرزيك من پولندا.[18] هناك تبادل لإطلاق النار بشكل يومي تقريباً.[19] وقعت انتهاكات كبرى لوقف إطلاق النار في مناسبات مختلفة،[20] والتي تتسم بعمليات قتالية محدودة.[21] من أبرز هذه الانتهاكات تلك التي وقعت في أبريل 2016،[22] عندما تغير الوضع على خط التماس لأول مرة منذ وقف إطلاق النار، لكن ليس بشكل كبير.[23] طبقاً لما قاله لورانس برويرز من تشاتام هاوس "على الرغم من سيطرتهم على بعض الأجزاء من الأراضي، لأول مرة منذ عام 1994، يبدو أن تغير الوضع على الأرض يحمل القليل من الأهمية الإستراتيجية".[24] كما شهدت اشتباكات 2016 أول استخدام للمدفعية الثقيلة منذ وقف إطلاق النار عام 1994.[25]

الوقع

حسب كولوسوڤ وزوتوڤا (2020)، "انتشار الوحدات العسكرية على امتداد الخط الفاصل، والنظام الخاص للمنطقة الحدودية على الجانبين، والمناوشات المستمرة، وتدمير عدد من المدن والمستوطنات خلال الحرب وبعدها مباشرة قد حول المناطق الحدودية إلى صحراء اقتصادية".[26]

حسب مجموعة الأزمات الدولية، فإن جميع الأرمن في قرةباخ، والبالغ عددهم 150.000 شخص، هم "تحت تهديد الصواريخ وقذائف المدفعية الأذربيجانية"، بينما يعيش حوالي ضعف عدد الأذربيجانيين (300.000)" في المنطقة التي يبلغ عرضها 15 كم على طول الجانب الأذربيجاني من خط التماس".[27]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Smolnik, Franziska (2016). Secessionist Rule: Protracted Conflict and Configurations of Non-state Authority. Campus Verlag. p. 12. ISBN 9783593506296.

- ^ "David Simonyan: Surrender of territories to Azerbaijan: Consequences for Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh". Noravank Foundation. 21 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

the northern flank – by the hard-to-access Mrav mountain range

- ^ Elbakyan, Edgar (16 May 2014). "Արցախի տարածքն անբաժանելի է". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in الأرمنية). Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

բնական սահմաններ հասցնելու համար, որը հյուսիսում Մռավի լեռնաշղթան է, իսկ հարավում՝ Արաքս գետը

- ^ Freizer, Sabine (2014). "Twenty years after the Nagorny Karabakh ceasefire: an opportunity to move towards more inclusive conflict resolution". Caucasus Survey. 1 (2): 2. doi:10.1080/23761199.2014.11417295.

- ^ أ ب ت de Waal, Thomas (24 July 2013). "The Two NKs". Carnegie Moscow Center. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Statement by the Co-Chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group on the Twentieth Anniversary of the Ceasefire Agreement". osce.org. 11 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017.

...the perpetual threat of escalating violence along the international border and the Line of Contact...

- ^ "Ոչ թե շփման գիծ, այլ սահման". a1plus (in الأرمنية). 9 March 2011.

- ^ Jamalyan, Davit (26 July 2012). "Ոչ թե շփման գիծ, այլ՝ պետական սահման". Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (in الأرمنية).

- ^ Hakobyan, Tatul (11 January 2018). "Հայաստան-Ադրբեջան սահմաններն ու "սահմանադռները"". CivilNet (in الأرمنية).

- ^ "Results of the Armenian aggression". ccla.lu. Chamber Of Commerce Luxembourg-Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019.

- ^ Hakobyan, Tatul (24 March 2018). "Emil Sanamyan: Nakhichevan Remains the Quietest Stretch of Armenian-Azerbaijani Frontline". civilnet.am. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (2 April 2016). "Dangerous Days in Karabakh". Carnegie Moscow Center. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019.

- ^ Bagirova, Nailia; Mkrtchyan, Hasmik (4 April 2016). "Armenia warns Nagorno-Karabakh clashes could turn into all-out war". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019.

- ^ Kao, Lauren (11 May 2016). "Eight Things You Need to Know About Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict". Eurasian Research and Analysis (ERA) Institute. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (3 April 2016). "Nagorno-Karabakh's cocktail of conflict explodes again". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019.

- ^ Toal, Gerard; O'Loughlin, John (6 April 2016). "Here are the 5 things you need to know about the deadly fighting in Nagorno Karabakh". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lynch, Dov (2001). "Frozen Conflicts". The World Today. 57 (8/9): 36–38. JSTOR 40476575.

The 'line of contact' between Azeri and Armenian forces is a trench system reminiscent of World War One.

- ^ Kucera, Joshua (8 April 2016). "Nagorno-Karabakh: Trying to Separate Fact from Fiction". EurasiaNet. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019.

- ^ Cristescu, Roxana; Paul, Amanda (15 March 2011). "EU and Nagorno-Karabakh: a 'better than nothing' approach". EUobserver.

- ^ Lynch, Dov (2004). Engaging Eurasia's Separatist States: Unresolved Conflicts and de Facto States. United States Institute of Peace. ISBN 9781929223541.

The line of contact between Azerbaijani and Armenian forces is a well-defined trench system, which experiences only occasional violations of the cease-fire regime.

- ^ "The conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh". The Economist. 15 April 2016.

But despite the ceasefire, low-scale fighting continued along the line of contact.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh violence: Worst clashes in decades kill dozens". BBC News. 3 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019.

- ^ Simão, Licínia (June 2016). "The Nagorno-Karabakh redux" (PDF). European Union Institute for Security Studies: 2. doi:10.2815/58373. ISSN 2315-1129.

For the first time since the 1990s, Azerbaijani forces managed to regain control of small parts of the territory surrounding Karabakh – the first time the Line of Contact has shifted. Although these changes do not significantly alter the parties' military predicament on the ground...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Defaulting to War" (PDF). chathamhouse.org. July 2016. p. 2.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (2 April 2016). "Fighting Between Azerbaijan and Armenia Flares Up in Nagorno-Karabakh". The New York Times.

The separatist government of Nagorno-Karabakh, whose principal backers are Armenia and Armenian diaspora groups in Southern California and elsewhere, characterized the fighting as the first time since 1994 that all types of heavy weaponry were being used along the front line.

- ^ Kolosov, Vladimir A.; Zotova, Maria V. (2020). "Multiple borders of Nagorno-Karabakh". Geography, Environment, Sustainability. 13: 88. doi:10.24057/2071-9388-2020-04.

- ^ "Armenia's Change of Leadership Adds Uncertainty over Nagorno-Karabakh". International Crisis Group. 19 July 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019.