المقتدي بأمر الله أبو القاسم عبد الله

| Al-Muqtadi المقتدي | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalīfah Amir al-Mu'minin | |||||||||

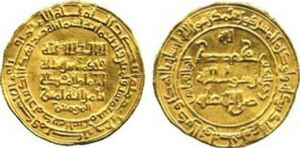

Gold dinar of al-Muqtadi | |||||||||

| 27th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad | |||||||||

| العهد | 2 April 1075 – 3 February 1094 | ||||||||

| سبقه | Al-Qa'im | ||||||||

| تبعه | Al-Mustazhir | ||||||||

| وُلِد | 24 July 1056 Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||||

| توفي | 3 فبراير 1094 (aged 37) Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||||

| Consort |

| ||||||||

| الأنجال | Al-Mustazhir Jafar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| الأسرة | Abbasid | ||||||||

| الأب | Muhammad | ||||||||

| الأم | Urjuman | ||||||||

| الديانة | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

المقتدي بأمر الله أبو القاسم عبد الله، هو أبو القاسم عبد الله بن محمد بن القائم بأمر الله المقتدى بأمر الله من خلفاء الدولة العباسية. ولد بعد وفاة أبيه بستة أشهر في عام 448 هـ. أمه أم ولد اسمها أرجوان.

الخلافة

بويع له بالخلافة عند موت جده وله تسع عشرة سنة وثلاثة أشهر وكانت البيعة بحضرة الشيخ أبي إسحاق الشيرازي وابن الصباغ والدامغاني وظهر في أيامه خيرات كثيرة وآثار حسنة في البلدان. وكانت قواعد الخلافة في أيامه باهرة وافرة الحرمة بخلاف من تقدمه. ومن محاسنه أنه نفى المغنيات والخواطي ببغداد وأمر أن لا يدخل أحد الحمام إلا بمئزر وخرب أبراج الحمام صيانة لحرم الناس. وكان ديناً خيراً قوي النفس عالي الهمة من نجباء بني العباس.

حدث في خلافته

في سنة 467هـ من خلافته أعيدت الخطبة للعبيدي بمكة وفيها جمع نظام الملك المنجمين وجعلوا النيروز أول نقطة من الحمل وكان قبل ذلك عند حلول الشمس نصف الحوت وصار ما فعله النظام مبدأ التقاويم.

- في سنة 468هـ خطب للمقتدي بدمشق وأبطل الأذان بحي على خير العمل وفرح الناس بذلك.

- في سنة 469هـ قدم بغداد أبو نصر بن الأستاذ أبي القاسم القشيري حاجاً فوعظ بالنظامية وجرى له فتنة كبيرة مع الحنابلة لأنه تكلم على مذهب الأشعري وحط عليهم وكثر أتباعه والمتعصبون له فهاجت فتن وقتلت جماعة. وعزل فخر الدولة بن جهير من وزارة المقتدي لكونه شذ عن الحنابلة.

- في سنة 475هـ بعث الخليفة الشيخ أبا إسحاق الشيرازي رسولا إلى السلطان يتضمن الشكوى من العميد أبي الفتح بن أبي الليث عميد العراق.

- في سنة 476هـ رخصت الأسعار بسائر البلاد وارتفع الغلاء. وفيها ولى الخليفة أبا الشجاع محمد بن الحسين الوزارة ولقبه ظهير الدين وأظن ذلك أول حدوث التلقيب بالإضافة إلى الدين.

- في سنة 477هـ سار سليمان بن قتلمش السلجوقي صاحب قونية وأقصراء بجيوشه إلى الشام فأخذ إنطاكية وكانت بيد الروم من سنة 358هـ وأرسل إلى السلطان ملكشاه يبشره قال الذهبي: وآل سلجوق هم ملوك بلاد الروم وقد امتدت أيامهم وبقي منهم بقية إلى زمن الملك الظاهر بيبرس.

- في سنة 478هـ جاءت ريح سوداء ببغداد بعد العشاء واشتد الرعد والبرق وسقط الرمل وتراب كالمطر ووقعت عدة صواعق في كثير من البلاد فظن الناس أنها القيامة وبقيت ثلاث ساعات بعد العصر وقد شاهد هذه الكائنة الإمام أبو بكر الطرطوشي وأوردها في أماليه.

- في سنة 479هـ أرسليوسف بن تاشفين صاحب سبتة ومراكش إلى المقتدي يطلب أن يسلطنه وأن يقلده ما بيده من البلاد فبعث إليه الخلع والأعلام والتقليد ولقبه بأمير المسلمين ففرح بذلك وسر به فقهاء المغرب وهو الذي أنشأ مدينة مراكش. وفيها دخل السلطان ملكشاه بغداد في ذي الحجة وهو أول من دخوله إليها فنزل بدار المملكة ولعب بالكرة وقد تقاوم الخليفة ثم رجع إلى أصبهان. وفيها قطعت خطبة العبيدي بالحرمين وخطب للمقتدي.

- في سنة 481هـ مات ملك غزنة المؤيد إبراهيم بن مسعود بن محمود بن سبكتين وقام مقامه ابنه جلال الدين مسعود.

- في سنة 483هـ عملت ببغداد مدرسة لتاج الملك مستوفي الدولة بباب أبرز ودرس بها أبو بكر الشاشي.

- في سنة 484هـ استولت الفرنج على جميع جزيرة صقلية وهي أول ما فتحها المسلمون بعد المائتين وحكم عليها آل الأغلب دهراً إلى أن استولى العبيدي المهدي على المغرب. وفيها قدم السلطان ملكشاه بغداد وأمر بعمل جامع كبير بها وعمل الأمراء حوله دوراً ينزلونها ثم رجع إلى أصبهان.

- في سنة 485هـ عاد السلطان ملكشاه إلى بغداد عازماً على الشر وأرسل إلى الخليفة يقول: لا بد أن تترك لي بغداد وتذهب إلى أي بلد شئت فانزعج الخليفة وقال: أمهلني ولو شهراً قال: ولا ساعة واحدة فأرسل الخليفة إلى وزير السلطان يطلب المهلة إلى عشرة أيام فاتفق مرض السلطان ومات وعد ذلك كرامة للخليفة وقيل: إن الخليفة جعل يصوم فإذا أفطر جلس على الرماد ودعا على ملكشاه فاستجاب الله دعاءه ولما مات كتمت زوجته تركان خاتون موته وأرسلت إلى الأمراء سراً فاستحلفتهم لولده محمود وهو ابن خمس سنين فحلفوا له وأرسلت إلى المقتدي في أن يسلطنه فأجاب ولقبه ناصر الدنيا والدين.

Meanwhile, Amid ad-Dawla had left for Isfahan once he heard of Nizam al-Mulk's plans.[1][2] He took a circuitous route through the mountains to avoid running into Gohar-A'in on the way, and he reached Isfahan on 23 July – the same day that Gohar A'in reached Baghdad.[1][2] Amid ad-Dawla met with Nizam al-Mulk and the two parties eventually reconciled, which they sealed with a marriage contract between Nizam al-Mulk's granddaughter and Amid ad-Dawla.[1][2] Al-Muqtadi did not initially rehire the Banu Jahir and instead kept them under house arrest, but Nizam al-Mulk later intervened and got them rehired.[1][2]

Also during Ramadan of 1078 (March–April), Fakhr ad-Dawla had had a minbar (pulpit) made at his expense and bearing the titles of al-Muqtadi.[2] It later ended up broken up and burned down.[2]

In 1081, the caliph sent Fakhr ad-Dawla to Isfahan, laden with gifts and over 20,000 dinars, to negotiate marriage with Malik-Shah's daughter.[1] Malik-Shah was grieving the death of his son Da'ud and did not take part i; the negotiations; rather, Fakhr ad-Dawla went to Nizam al-Mulk.[1] The two worked together this time; they went to the princess's foster mother, Turkan Khatun, to make their request.[1] She was disinterested at first because the Ghaznavid ruler had made a better offer: 100,000 dinars.[1][2] Khadija Arslan Khatun, who had been married to al-Qa'im, told her that a marriage with the caliph would be more prestigious, and that she should not be asking the caliph for more money.[2]

Eventually, Turkan Khatun agreed to the marriage, but with heavy conditions imposed on al-Muqtadi: in return for marrying the Seljuk princess, al-Muqtadi would pay 50,000 dinars plus an additional 100,000 dinars as mahr (bridal gift), give up his current wives and concubines, and agree to not have sexual relations with any other woman.[1] This was an especially heavy significant burden on the Abbasid caliph, since the Abbasids had been tightly controlling their "reproductive politics", with all their heirs being born to umm walads and therefore unrelated to any rival dynasties.[1] By agreeing to Turkan Khatun's terms, Fakhr ad-Dawla was putting al-Muqtadi at a severe disadvantage while also benefitting the Seljuks considerably.[1]

In 1083, al-Muqtadi removed the Banu Jahir from office by decree.[1] The circumstances of their removal from office are somewhat unclear - historians gave varying accounts.[1] In Sibt ibn al-Jawzi's version, al-Muqtadi had become suspicious of the Banu Jahir, prompting them to leave for Khorasan without requesting official permission; this further aroused al-Muqtadi's suspicions and he retroactively fired them after they had left.[1] He then wrote to the Seljuks, telling them not to employ the Banu Jahir in their administration.[1] In Ibn al-Athir's version, the Seljuks at some point approached al-Muqtadi and asked to employ the Banu Jahir themselves, and al-Muqtadi agreed.[1] Al-Bundari offers no details about the firing itself but wrote instead that the Seljuks sent representatives to meet the Banu Jahir in Baghdad (rather than in Khorasan).[1]

According to Ibn al-Athir's account, the Banu Jahir left Baghdad on Saturday, 22 July 1083.[2] They were succeeded as viziers by Abu'l-Fath al-Muzaffar, son of the ra'is al-ru'asa', who had previously been "in charge of the palace buildings".[2]

Al-Muqtadi was honored by the Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah I, during whose reign the Caliphate was recognized throughout the extending range of Seljuk conquest. Arabia, with the Holy Cities, now recovered from the Fatimids, acknowledged again the spiritual jurisdiction of the Abbasids.

Malik-Shah I arranged a marriage between his daughter and al-Muqtadi, possibly planning on the birth of a son who could serve as both caliph and sultan. Though the couple had a son, the mother left with her infant to the court of Isfahan. Following the failure of the marriage, the Sultan grew critical of the Caliph's interference in affairs of state, and sent an order for him to retire to Basra. The death of Malik-Shah I shortly after, however, made the command inoperative.

In 1092, when Malik Shah I was assassinated shortly after Nizam al-Mulk, Taj al-Mulk nominated Mahmud as Sultan and set out for Isfahan.[3] Mahmud was a child, and his mother Terken Khatun wished to seize power in his stead. To accomplish this, she entered negotiations with the Caliph al-Muqtadi to secure her rule. The Caliph opposed both a child and a woman as ruler, and could not be persuaded to allow the khutba, the sign of the sovereign, to be proclaimed in the name of a woman. Eventually, however, the Caliph agreed to let her govern if the khutba was said in the name of her son, and if she did so assisted by a vizier he appointed for her, a condition she saw herself forced to accept.[4]

العائلة

Al-Muqtadi's first wife was Sifri Khatun. She was the daughter of Sultan Alp Arslan.[5] In 1071–72, his father Al-Qa'im sent his wazir Ibn Al-Jahir to ask her hand in marriage, to which demand the Sultan agreed.[6] His second wife was Mah-i Mulk Khatun, daughter of Sultan Malik-Shah I. In March 1082, Al-Muqtadi sent Abu Nasr ibn Jahir to Malik Shah in Isfahan to ask for her hand in marriage. Her father gave his consent and the marriage contract was concluded. She arrived Baghdad in March 1087. The marriage was consummated in May 1087. She gave birth to Prince Ja'far on 31 January 1088. But then Al-Muqtadi began to avoid her and she asked permission to return home. She left Baghdad for Khurasan on 29 May 1089, accompanied by her son. Subsequently, news of her death reached Baghdad. Her ailing father, brought her son back to Baghdad in October 1092. Prince Ja'far was taken back to the Caliphal Palace, where he remained until his death on 21 June 1093. He was buried near the caliphal tombs in the Rusafah Cemetery.[7] One of Al-Muqtadi's concubines was Kalbahaar or Jalb'har, also known as Tayf al-Khayal. She was a Turkish and was the mother of caliph Al-Mustazhir.[8]

وفاته

في المحرم سنة 487هـ خرج علي الخليفة أخو محمود بن ملكشاه بركياروق بن ملكشاه فقلده الخليفة ولقبه ركن الدين وعلم الخليفة على تقليده ثم مات الخليفة من الغد فجأة فقيل: إن جاريته شمس النهار سمته وبويع لولده المستظهر.

مات في عهده

مات في أيام المقتدى من الأعلام: عبد القادر الجرجاني وأبو الوليد الباجي والشيخ أبو إسحاق الشيرازي والأعلم النحوي وابن الصباغ صاحب الشامل والمتولي وإمام الحرمين والدامغاني الحنفي وابن فضالة المجاشعي والبزدوي شيخ الحنفية.

التعاقب

Al-Muqtadi died in 1094 at the age of 37–38. He was succeeded by his 16-year-old son Ahmad al-Mustazhir as Caliph.

انظر أيضاً

- Banu Jahir, family of viziers that were prominent under al-Muqtadi's reign

المراجع

- This text is adapted from William Muir's public domain, The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline, and Fall.

المقتدي بأمر الله أبو القاسم عبد الله وُلِد: ? توفي: 1094

| ||

| ألقاب إسلامية سنية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Al-Qa'im |

Caliph of Islam 1075 – 1094 |

تبعه Al-Mustazhir |

مصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHanne 2008 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةIbn al-Athir - ^ Boyle 1968, p. 103.

- ^ Mernissi, Fatima; Mary Jo Lakeland (2003). The forgotten queens of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579868-5.

- ^ El-Hibri, T. (2021). The Abbasid Caliphate: A History. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-107-18324-7.

- ^ Lambton, A.K.S. (1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. Bibliotheca Persica. Bibliotheca Persica. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-88706-133-2.

- ^ al-Sāʿī, Ibn; Toorawa, Shawkat M.; Bray, Julia (2017). كتاب جهات الأئمة الخلفاء من الحرائر والإماء المسمى نساء الخلفاء: Women and the Court of Baghdad. Library of Arabic Literature. NYU Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4798-6679-3.

- ^ Rudainy, Al; Saud, Reem (12 يونيو 2015). "The Role of Women in the Būyid and Saljūq Periods of the Abbasid Caliphate (339-447/9501055&447-547/1055-1152): The Case of Iraq". University of Exeter. pp. 117, 157. Retrieved 14 أبريل 2024.

- ^

السيوطي, جلال الدين. تاريخ الخلفاء.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)