الجانب البعيد من القمر

الجانب البعيد من القمر far side of the Moon، أو الجانب المظلم من القمر Dark side of the Moon، هو نصف القمر الذي دائماً لا يكون في مواجهة الأرض. تضاريس الجانب البعيد وعرة وتحتوي على العديد من الفوهات الصدمية ونسبة قليلة نسبياً من البحار القمرية. يحتوي القمر على واحدة من أكبر فوهات المجموعة الشمسية، حوض قطب-أتيكن الجنوبي. يتمتع جانبي القمر بأسبوعين من النهار تليها أسبوعين الليل؛ يسمى الجانب البعيد أحياناً "الجانب المظلم من القمر"، أي، الجانب الذي الغير مرئي وليس الجانب الذي يفتقد الضوء.[1][2][3][4]

حوالي 18% من الجانب البعيد يمكن رؤيتها أحياناً من الأرض بسبب الميسان. الـ82% الباقية لم تُرصد حتى عام 1959، عندما صورها مسبار الفضاء لونا 3. نشرت الأكاديمية السوڤيتية للعلوم أول أطلس للجانب البعيد عام 1960. وكان رواد فضاء أپولو 8 أول بشر يرون الجانب المظلم بالعين المجردة عندما داروا حول القمر عام 1969. جميع عمليات الهبوط الناعم، سواء المأهولة أو الغير مأهولة، جرت على الجانب القريب من القمر، حتى 3 يناير 2019، عندما قامت مركبة الفضاء الصينية تشانگ-إ4 بأول هبوط على الجانب البعيد.[5]

يقترح علماء الفضاء تركيب تلسكوب راديوي ضخم على الجانب البعيد، حيث يمكنه حماية القمر من التداخل الراديوي المحتمل من الأرض.[6]

تعريف

Tidal forces from Earth have slowed the Moon's rotation to the point where the same side is always facing the Earth—a phenomenon called tidal locking. The other face, most of which is never visible from the Earth, is therefore called the "far side of the Moon". Over time, some crescent-shaped edges of the far side can be seen due to libration.[7] In total, 59 percent of the Moon's surface is visible from Earth at one time or another. Useful observation of the parts of the far side of the Moon occasionally visible from Earth is difficult because of the low viewing angle from Earth (they cannot be observed "full on").

A common misconception is that the Moon does not rotate on its axis. If that were so, the whole of the Moon would be visible to Earth over the course of its orbit. Instead, its rotation period matches its orbital period, meaning it turns around once for every orbit it makes: in Earth terms, it could be said that its day and its year have the same length (i.e., ~29.5 earth days).

The phrase "dark side of the Moon" does not refer to "dark" as in the absence of light, but rather "dark" as in unknown: until humans were able to send spacecraft around the Moon, this area had never been seen.[1][2][3] In reality, both the near and far sides receive (on average) almost equal amounts of light directly from the Sun. This symmetry is complicated by sunlight reflected from the Earth onto the near side (earthshine),[8] and by lunar eclipses, which occur only when the far side is already dark.

At night under a "full Earth" the near side of the Moon receives on the order of 10 lux of illumination (about what a city sidewalk under streetlights gets; this is 34 times more light than is received on Earth under a full Moon) whereas the dark side of the Moon during the lunar night receives only about 0.001 lux of starlight.[8] Only during a full Moon (as viewed from Earth) is the whole far side of the Moon dark.

The word dark has expanded to refer also to the fact that communication with spacecraft can be blocked while the spacecraft is on the far side of the Moon, during Apollo space missions for example.[9]

الاختلافات

يتميز كلا الجانبين بسمات مميزة، فيغطي الجانب القريب من القمر بعدد كبير من البحار القمرية. في حين تعرض الجانب البعيد للعديد من الاصطدامات بدلالة وجود عدد كبير من الفوهات الصدمية في حين أن عدد البحار القمرية قليل، ففقط 2.5% من سطح الجانب البعيد مغطى بالبحار القمرية،[10] بالمقارنة مع 31.2% من سطح الجانب القريب مغطى بالبحار القمرية. وأكثر تفسير مقبول لهذا التباين في التوزيع هو وجود كميات كبيرة من تركيز العناصر المنتجة للحرارة في الجانب القريب. وقد تم التأكد من هذا باستخدام مطياف أشعة گاما للمسبار لونار بروسبكتر. While other factors, such as surface elevation and crustal thickness, could also affect where basalts erupt, these do not explain why the far side South Pole–Aitken basin (which contains the lowest elevations of the Moon and possesses a thin crust) was not as volcanically active as Oceanus Procellarum on the near side.

It has also been proposed that the differences between the two hemispheres may have been caused by a collision with a smaller companion moon that also originated from the Theia collision.[11] In this model, the impact led to an accretionary pile rather than a crater, contributing a hemispheric layer of extent and thickness that may be consistent with the dimensions of the far side highlands. However, the chemical composition of the far side is inconsistent with this model.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The far side has more visible craters. This was thought to be a result of the effects of lunar lava flows, which cover and obscure craters, rather than a shielding effect from the Earth. NASA calculates that the Earth obscures only about 4 square degrees out of 41,000 square degrees of the sky as seen from the Moon. "This makes the Earth negligible as a shield for the Moon [and] it is likely that each side of the Moon has received equal numbers of impacts, but the resurfacing by lava results in fewer craters visible on the near side than the far side, even though both sides have received the same number of impacts."[12]

Newer research suggests that heat from Earth at the time when the Moon was formed is the reason the near side has fewer impact craters. The lunar crust consists primarily of plagioclases formed when aluminium and calcium condensed and combined with silicates in the mantle. The cooler far side experienced condensation of these elements sooner and so formed a thicker crust; meteoroid impacts on the near side would sometimes penetrate the thinner crust here and release basaltic lava that created the maria, but would rarely do so on the far side.[13]

الإستكشاف

الاستكشاف المبكر

حتى أواخر 1950 كان معلومات قليلة جداً معروفة عن خصائص الجانب البعيد من القمر. فقد كانت ميسان القمر يسمح دورياً بلمحات محدود من ملامح طرف الجانب البعيد . كان ينظر لهذه الملامح من زاوية منخفضة، مما أعاق المراقبة المفيدة. (ثبت أن من الصعب التمييز بين حفرة من سلسلة جبال.) أما النسبة المتبقية 82٪ من السطح على الجانب الآخر فبقي مجهولا، وخضعت خصائصه إلى الكثير من التكهنات.

إحدى الأمثلة التي من الممكن رؤيتها من خلال ميسان القمر هو البحر الشرقي وهو حوض يمتد حوالي 1000 كم .

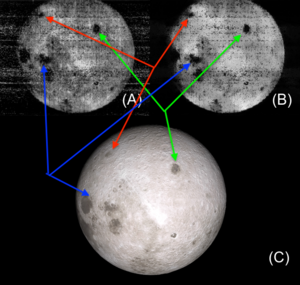

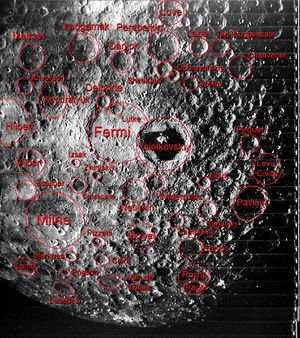

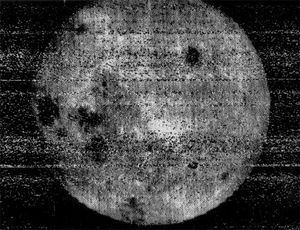

إلتقط المسبار لونا 3 في 7 أكتوبر 1959 أول صور للجانب البعيد من القمر،[14] وقد غطت هذه الصور ثلث سطح الجانب البعيد من القمر.[15] وقد صدر أول أطلس للجانب البعيد من القمر عن الأكاديمية السوفيتية للعلوم بعد أن تم تحليل هذه الصور في 6 نوفمبر 1960،[16] وقد شمل أكثر من 500 من ملامح الجانب البعيد ضمنه[17] وفي سنة 1965 قام مسبار سوفيتي آخر زوند 3 أرسل 25 صورة عالية الوضوح للجانب البعيد من القمر.[18] وصدر الجزء الثاني من الأطلس في موسكو سنة 1967.[19][20]

In 1961, the first globe (1:13600000 scale)[21] containing lunar features invisible from the Earth was released in the USSR, based on images from Luna 3.[22] On 20 July 1965, another Soviet probe, Zond 3, transmitted 25 pictures of very good quality of the lunar far side,[23] with much better resolution than those from Luna 3. In particular, they revealed chains of craters, hundreds of kilometers in length,[15] but, unexpectedly, no mare plains like those visible from Earth with the naked eye.[24]

In 1967, the second part of the Atlas of the Far Side of the Moon was published in Moscow,[25][26] based on data from Zond 3, with the catalog now including 4,000 newly discovered features of the lunar far side landscape.[15] In the same year, the first Complete Map of the Moon (1:5000000 scale[21]) and updated complete globe (1:10000000 scale), featuring 95 percent of the lunar surface,[21] were released in the Soviet Union.[27][28]

As many prominent landscape features of the far side were discovered by Soviet space probes, Soviet scientists selected names for them. This caused some controversy, and the International Astronomical Union, leaving many of those names intact, later assumed the role of naming lunar features on this hemisphere.

مهمة لمزيد من المسح

On 26 April 1962, NASA's Ranger 4 space probe became the first spacecraft to impact the far side of the Moon, although it failed to return any scientific data before impact.[29]

The first truly comprehensive and detailed mapping survey of the far side was undertaken by the American uncrewed Lunar Orbiter program launched by NASA from 1966 to 1967. Most of the coverage of the far side was provided by the final probe in the series, Lunar Orbiter 5.

أما أول رصد مباشر للجانب البعيد من القمر بالعين البشرية فكان سنة 1968 بواسطة رائدي فضاء البعثة أپولو 8.

“The backside looks like a sand pile my kids have played in for some time. It's all beat up, no definition, just a lot of bumps and holes.”

It has been seen by all 24 men who flew on Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 through Apollo 17, and photographed by multiple lunar probes. Spacecraft passing behind the Moon were out of direct radio communication with the Earth, and had to wait until the orbit allowed transmission. During the Apollo missions, the main engine of the Service Module was fired when the vessel was behind the Moon, producing some tense moments in Mission Control before the craft reappeared.

Geologist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt, who became the last to step onto the Moon, had aggressively lobbied for his landing site to be on the far side of the Moon, targeting the lava-filled crater Tsiolkovskiy. Schmitt's ambitious proposal included a special communications satellite based on the existing TIROS satellites to be launched into a Farquhar–Lissajous halo orbit around the L2 point so as to maintain line-of-sight contact with the astronauts during their powered descent and lunar surface operations. NASA administrators rejected these plans on the grounds of added risk and lack of funding.

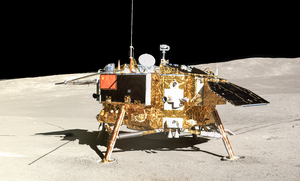

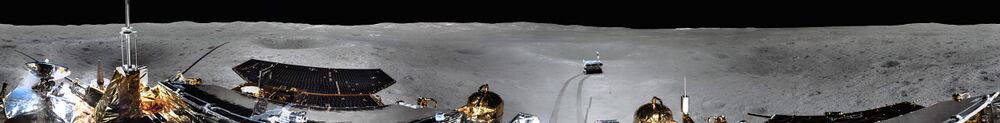

The idea of utilizing Earth–Moon ل2 for communications satellite covering the Moon's far side has been realized, as China National Space Administration launched Queqiao relay satellite in 2018.[30] It has since been used for communications between the Chang'e 4 lander and Yutu 2 rover that have successfully landed in early 2019 on the lunar far side and ground stations on the Earth. And L2 is proposed to be "an ideal location" for a propellant depot as part of the proposed depot-based space transportation architecture.[31]

هبوط سلس

قامت المركبة الفضائية تشانگ-إ4 التابعة لإدارة الفضاء الوطنية الصينية في 3 يناير 2019 بأول هبوط ناعم على الجانب البعيد من القمر.[32]تتضمن المهمة مركبة هبوط مجهزة بمطياف راديوي منخفض التردد وأدوات بحث جيولوجي.[33]

In February 2020, Chinese astronomers reported, for the first time, a high-resolution image of a lunar ejecta sequence, and, as well, direct analysis of its internal architecture. These were based on observations made by the Lunar Penetrating Radar (LPR) on board the Yutu-2 rover.[34][35]

The Lunar Surface Electromagnetics Experiment (LuSEE-Night) lander, a mission to soft land as early as 2026 a robotic observatory on the far side designed to measure electromagnetic waves from the early history of the universe is being developed by NASA and the United States Department of Energy.[36]

الاستخدامات المحتملة والمهام

Because the far side of the Moon is shielded from radio transmissions from the Earth, it is considered a good location for placing radio telescopes for use by astronomers. Small, bowl-shaped craters provide a natural formation for a stationary telescope similar to Arecibo in Puerto Rico. For much larger-scale telescopes, the 100-كيلومتر-diameter (60 mi) crater Daedalus is situated near the center of the far side, and the 3-كيلومتر-high (2 mi) rim would help to block stray communications from orbiting satellites. Another potential candidate for a radio telescope is the Saha crater.[37]

Before deploying radio telescopes to the far side, several problems must be overcome. The fine lunar dust can contaminate equipment, vehicles, and space suits. The conducting materials used for the radio dishes must also be carefully shielded against the effects of solar flares. Finally, the area around the telescopes must be protected against contamination by other radio sources.

The ل2 Lagrange point of the Earth–Moon system is located about 62،800 km (39،000 mi) above the far side, which has also been proposed as a location for a future radio telescope which would perform a Lissajous orbit about the Lagrangian point.

One of the NASA missions to the Moon under study would send a sample-return lander to the South Pole–Aitken basin, the location of a major impact event that created a formation nearly 2،400 km (1،500 mi) across. The force of this impact has created a deep penetration into the lunar surface, and a sample returned from this site could be analyzed for information concerning the interior of the Moon.[38]

Because the near side is partly shielded from the solar wind by the Earth, the far side maria are expected to have the highest concentration of helium-3 on the surface of the Moon.[39] This isotope is relatively rare on the Earth, but has good potential for use as a fuel in fusion reactors. Proponents of lunar settlement have cited the presence of this material as a reason for developing a Moon base.[40]

الأطباق الطائرة المزعومة والمؤامرات

تضاريس مسماة

- Aitken (crater)

- Amici (crater)

- Anuchin (crater)

- Apollo (crater)

- Bel'kovich (crater)

- Belopol'skiy (crater)

- Bergstrand (crater)

- Berkner (crater)

- Bok (lunar crater)

- Bjerknes (lunar crater)

- Cantor (crater)

- Cassegrain (crater)

- Comrie (crater)

- Crookes (crater)

- Daedalus (crater)

- Davisson (crater)

- Ellerman (crater)

- Finsen (crater)

- Fridman (crater)

- Gerasimovich (crater)

- Hayn (crater)

- Hertzsprung (crater)

- Houzeau (crater)

- Icarus (crater)

- Ioffe (crater)

- Jenner (crater)

- Kamerlingh Onnes (crater)

- Kolhörster (crater)

- Komarov (crater)

- Kugler (crater)

- Lamb (crater)

- Lacus Oblivionis

- Lander (crater)

- Lebedev (crater)

- Leibnitz (crater)

- Lucretius (crater)

- Lunar south pole

- Maksutov (crater)

- McKellar (crater)

- Mare Australe

- Mare Frigoris

- Mare Humboldtianum

- Mare Ingenii

- Mare Moscoviense

- Mare Orientale

- Mendeleev (crater)

- Michelson (crater)

- Montes Cordillera

- Montes Rook

- Mons Tai[41][42]

- Nicholson (lunar crater)

- Nishina (crater)

- Ohm (crater)

- Oppenheimer (crater)

- Oresme (crater)

- Pannekoek (crater)

- Paraskevopoulos (crater)

- Parenago (crater)

- Patsaev (crater)

- Perrine (crater)

- Pettit (lunar crater)

- Pirquet (crater)

- Pogson (crater)

- Priestley (lunar crater)

- Quetelet (crater)

- Rowland (crater)

- Sarton (crater)

- Schlesinger (crater)

- Shaler (crater)

- Shternberg (crater)

- Shuleykin (crater)

- Sniadecki (crater)

- Sommerfeld (crater)

- South Pole–Aitken basin

- Statio Tianhe[41][42]

- Stebbins (crater)

- Stoletov (crater)

- Sverdrup (crater)

- Tianjin (crater)[41][42]

- Tikhov (lunar crater)

- Titov (crater)

- Tsinger (crater)

- Tsiolkovskiy (crater)

- Tyndall (lunar crater)

- Vallis Bouvard

- Vallis Inghirami

- van't Hoff (crater)

- Van der Waals (crater)

- Vavilov (crater)

- Vertregt (crater)

- Volkov (crater)

- Von Kármán (lunar crater)

- Von Zeipel (crater)

- Wan-Hoo (crater)

- Wiener (crater)

- Wright (lunar crater)

- Yamamoto (crater)

- Zhinyu (crater)[41][42]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Sigurdsson, Steinn (2014-06-09). "The Dark Side of the Moon: a Short History". Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ^ أ ب O'Conner, Patricia T.; Kellerman, Stewart (2011-09-06). "The Dark Side of the Moon". Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ^ أ ب Messer, A'ndrea Elyse (2014-06-09). "55-year-old dark side of the moon mystery solved". Penn State News. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Falin, Lee (2015-01-05). "What's on the Dark Side of the Moon?". Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- ^ "Chinese spacecraft makes first landing on moon's far side". AP NEWS. 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ Kenneth Silber. "Down to Earth: The Apollo Moon Missions That Never Were".

- ^ NASA. "Libration of the Moon".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[dead link] - ^ أ ب "The Dark Side of the Moon". 18 January 2013.

- ^ "Dark No More: Exploring the Far Side of the Moon". 29 April 2013.

- ^ J. J. Gillis, P. D. Spudis (1996). "The Composition and Geologic Setting of Lunar Far Side Maria". Lunar and Planetary Science. 27: 413–404.

- ^ M. Jutzi; E. Asphaug (2011). "Forming the lunar farside highlands by accretion of a companion moon". Nature. 476 (7358): 69–72. Bibcode:2011Natur.476...69J. doi:10.1038/nature10289. PMID 21814278. S2CID 84558.

- ^ Near-side/far-side impact crater counts by David Morrison and Brad Bailey, NASA. http://lunarscience.nasa.gov/?question=3318. Accessed 9 January 2013.

- ^ Messer, A'ndrea Elyse (9 June 2014). "55-year-old dark side of the moon mystery solved". Penn State University. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Luna 3. ناسا Archived 2007-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت (بالروسية)الموسوعة السوفيتية العظمى، 3rd. edition, entry on "Луна (спутник Земли)", available online here

- ^ Aeronautics and Astronautics Chronology, 1960. ناسا Archived 2017-01-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (بالروسية) Chronology, 1804-1980, to the 150th anniversary of GAISh - Moscow State University observatory. MSU

- ^ Zond 3. ناسا Archived 2007-11-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ АТЛАС ОБРАТНОЙ СТОРОНЫ ЛУНЫ, Ч. 2, Moscow: Nauka, 1967

- ^ Observing the Moon Throughout History. قبة أدلر السماوية[[تصنيف:مقالات ذات وصلات خارجية مكسورة from خطأ: زمن غير صحيح.]]<span title=" منذ خطأ: زمن غير صحيح." style="white-space: nowrap;">[وصلة مكسورة] Archived 2007-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب ت (in روسية) Moon maps and globes, created with the participation of Lunar and Planetary Research Department of SAI. SAI

- ^ "Sphæra: the Newsletter of the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford". www.mhs.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ "NASA – NSSDCA – Spacecraft – Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةley196604 - ^ Atlas Obratnoy Storony Luny, p.2, Moscow: Nauka, 1967

- ^ "Observing the Moon Throughout History". Adler Planetarium (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ "Works of the Department of lunar and planetary research of GAISh MGU". selena.sai.msu.ru.

- ^ (in روسية) Moon Maps. MSU

- ^ "Discussion". Space Policy. 14 (1): 5–8. 1998. Bibcode:1998SpPol..14....5.. doi:10.1016/S0265-9646(97)00038-6.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (14 June 2018). "Chang'e-4 relay satellite enters halo orbit around Earth-Moon L2, microsatellite in lunar orbit". SpaceNews.

- ^ Zegler, Frank; Kutter, Bernard (2 September 2010). "Evolving to a Depot-Based Space Transportation Architecture" (PDF). AIAA SPACE 2010 Conference & Exposition. AIAA. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

L2 is in deep space far away from any planetary surface and hence the thermal, micrometeoroid, and atomic oxygen environments are vastly superior to those in LEO. Thermodynamic stasis and extended hardware life are far easier to obtain without these punishing conditions seen in LEO. L2 is not just a great gateway—it is a great place to store propellants. ... L2 is an ideal location to store propellants and cargos: it is close, high energy, and cold. More importantly, it allows the continuous onward movement of propellants from LEO depots, thus suppressing their size and effectively minimizing the near-Earth boiloff penalties.

- ^ "Chinese spacecraft makes first landing on moon's far side". Times of India. Associated Press. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "China aims to land Chang'e-4 probe on far side of moon". Xinhua English News. 2015-09-08. Archived from the original on 2015-09-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chang, Kenneth (26 February 2020). "China's Rover Finds Layers of Surprise Under Moon's Far Side - The Chang'e-4 mission, the first to land on the lunar far side, is demonstrating the promise and peril of using ground-penetrating radar in planetary science". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Li, Chunlai; et al. (26 February 2020). "The Moon's farside shallow subsurface structure unveiled by Chang'E-4 Lunar Penetrating Radar". Science Advances. 6 (9): eaay6898. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.6898L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay6898. PMC 7043921. PMID 32133404.

- ^ "NASA, Department of Energy Join Forces on Innovative Lunar Experiment". 6 March 2023.

- ^ Stenger, Richard (9 January 2002). "Astronomers push for observatory on the moon". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- ^ M. B. Duke; B. C. Clark; T. Gamber; P. G. Lucey; G. Ryder; G. J. Taylor (1999). "Sample Return Mission to the South Pole Aitken Basin" (PDF). Workshop on New Views of the Moon 2: Understanding the Moon Through the Integration of Diverse Datasets: 11.

- ^ "Thar's Gold in Tham Lunar Hills". Daily Record. 28 January 2006. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- ^ Schmitt, Harrison (7 December 2004). "Mining the Moon". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Chang'e-4's moon landing site named". China Daily. 17 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "IAU Names Landing Site of Chinese Chang'e-4 Probe on Far Side of the Moon". International Astronomical Union. 15 February 2019.

وصلات خارجية

- Lunar and Planetary Institute: Exploring the Moon

- [1]

- Lunar and Planetary Institute: Lunar Atlases

- Ralph Aeschliman Planetary Cartography and Graphics: Lunar Maps

- Northwest Africa 482, only meteorite believed to have originated from the far side of the Moon

- Moon articles in Planetary Science Research Discoveries

- Merrifield, Michael. "Far Side of the Moon". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- LIFE magazine (Nov. 9, 1959) article about first photos.