أوراق اللعب

أوراق اللعب playing card كما يطلق عليها بين العامة الكوتشينة وهي عادةً من قطعة من الورق الثقيل أو من البلاستيك الرقيق، وعددها 56 ورقة .وهي مجموعة كاملة من كروت تستخدم للعب واحدة من العديد من العاب الكروت، والتي تدخل في لعبة القمار. لأن كروت اللعب متاحة ، تستخدم أوراق اللعب لأغراض أخرى ، مثل الخدع السحرية،[1][2] card throwing,[3] أو بناء منزل من البطاقات؛cards may also be collected.[4] Playing cards are typically palm-sized for convenient handling, and usually are sold together in a set as a deck of cards or pack of cards.

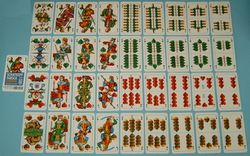

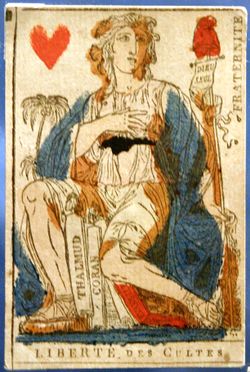

The most common type of playing card in the West is the French-suited, standard 52-card pack, of which the most widespread design is the English pattern,[أ] followed by the Belgian-Genoese pattern.[5] However, many countries use other, traditional types of playing card, including those that are German, Italian, Spanish and Swiss-suited. Tarot cards (also known locally as Tarocks or tarocchi) are an old genre of playing card that is still very popular in France, central and Eastern Europe and Italy. Customised Tarot card decks are also used for divination; including tarot card reading and cartomancy.[6] Asia, too, has regional cards such as the Japanese hanafuda, Chinese money-suited cards, or Indian ganjifa. The reverse side of the card is often covered with a pattern that will make it difficult for players to look through the translucent material to read other people's cards or to identify cards by minor scratches or marks on their backs.

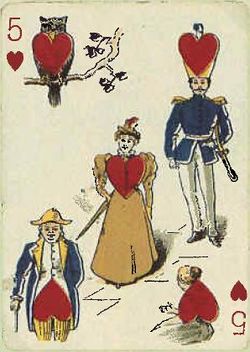

Playing cards are available in a wide variety of styles, as decks may be custom-produced for competitions, casinos[7] and magicians[8] (sometimes in the form of trick decks),[9] made as promotional items,[10] or intended as souvenirs,[11][12] artistic works, educational tools,[13][14][15] or branded accessories.[16] Decks of cards or even single cards are also collected as a hobby or for monetary value.[17][18]

التاريخ

الصين

Playing cards were most likely invented during the Tang dynasty around the 9th century, as a result of the usage of woodblock printing technology.[19][20][21][22][23] The reference to a leaf game in a 9th-century text known as the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang (الصينية: 杜阳杂编; پنين: Dùyáng zábiān), written by Tang dynasty writer Su E, is often cited in connection to the existence of playing cards. However the connection between playing cards and the leaf game is disputed.[24][25][26][27] The reference describes Princess Tongchang, daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the "leaf game" in 868 with members of the Wei clan, the family of the princess's husband.[21][28][29] The first known book on the "leaf" game was called the Yezi Gexi and allegedly written by a Tang woman. It received commentary by writers of subsequent dynasties.[30] The Song dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserts that the "leaf" game existed at least since the mid-Tang dynasty and associated its invention with the development of printed sheets as a writing medium.[21][30] However, Ouyang also claims that the "leaves" were pages of a book used in a board game played with dice, and that the rules of the game were lost by 1067.[31]

Other games revolving around alcoholic drinking involved using playing cards of a sort from the Tang dynasty onward. However, these cards did not contain suits or numbers. Instead, they were printed with instructions or forfeits for whoever drew them.[31]

The earliest dated instance of a game involving cards occurred on 17 July 1294 when the Ming Department of Punishments caught two gamblers, Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Zhugou[ب], playing with paper cards. Wood blocks for printing the cards were impounded, together with nine of the actual cards.[31][32]

William Henry Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which doubled as both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for,[20] similar to trading card games. Using paper money was inconvenient and risky so they were substituted by play money known as "money cards". One of the earliest games in which we know the rules is madiao, a trick-taking game, which dates to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Fifteenth-century scholar Lu Rong described it as being played with 38 "money cards" divided into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), 9 in myriads (of coins or of strings), and 11 in tens of myriads (a myriad is 10,000). The two latter suits had Water Margin characters instead of pips on them[33] with Chinese to mark their rank and suit. The suit of coins is in reverse order with 9 of coins being the lowest going up to 1 of coins as the high card.[34]

بلاد فارس

Despite the wide variety of different patterns, the suits show a uniformity of structure. Every suit contains twelve cards with the top two usually being the court cards of king and vizier and the bottom ten being pip cards. Some decks can contain 8 suits to make a 96-card deck, like the deck for Ganjifa. Half the suits use reverse ranking for their pip cards. There are many motifs for the suit pips but some include coins, clubs, jugs, and swords which resemble later Mamluk and Latin suits. Michael Dummett speculated that Mamluk cards may have descended from an earlier deck which consisted of 48 cards divided into four suits each with ten pip cards and two court cards.[35]

مصر

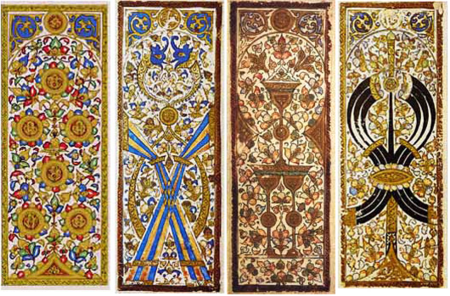

By the 11th century, playing cards were spreading throughout the Asian continent and later came into Egypt.[36] The oldest surviving cards in the world are four fragments found in the Keir Collection and one in the Benaki Museum.[ت] They are dated to the 12th and 13th centuries (late Fatimid, Ayyubid, and early Mamluk periods).[38]

A near complete pack of Mamluk playing cards dating to the 15th century, and of similar appearance to the fragments above, was discovered by Leo Aryeh Mayer in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, in 1939.[39] It is not a complete set and is actually composed of three different packs, probably to replace missing cards.[40] The Topkapı pack originally contained 52 cards comprising four suits: polo-sticks, coins, swords, and cups. Each suit contained ten pip cards and three court cards, called malik (king), nā'ib malik (viceroy or deputy king), and thānī nā'ib (second or under-deputy). The thānī nā'ib is a non-existent title so it may not have been in the earliest versions; without this rank, the Mamluk suits would structurally be the same as a Ganjifa suit. In fact, the word "Kanjifah" appears in Arabic on the king of swords and is still used in parts of the Middle East to describe modern playing cards. Influence from further east can explain why the Mamluks, most of whom were Central Asian Turkic Kipchaks, called their cups tuman, which means "myriad" (10,000) in the Turkic, Mongolian, and Jurchen languages.[41] Wilkinson postulated that the cups may have been derived from inverting the Chinese and Jurchen ideogram for "myriad", 万, which was pronounced as something like man in Middle Chinese.

The Mamluk court cards showed abstract designs or calligraphy not depicting persons possibly due to religious proscription in Sunni Islam, though they did bear the ranks on the cards. Nā'ib would be borrowed into French (nahipi), Italian (naibi), and Spanish (naipes), the latter word still in common usage. Panels on the pip cards in two suits show they had a reverse ranking, a feature found in madiao, ganjifa, and old European card games like ombre, tarot, and maw.[42] A fragment of two uncut sheets of Moorish-styled cards of a similar was found in Spain and dated to the early 15th century.[43]

Export of these cards (from Cairo, Alexandria, and Damascus), ceased after the fall of the Mamluks in the 16th century.[44] The rules to play these games are lost but they are believed to be plain trick games without trumps.[45]

انتشار أوراق اللعب في أوروبا

الإنتشار في جميع أنحاء أوروبا وتغييرات التصميم في وقت مبكر

| Modern Paris court card name | Traditional Paris court card name |

|---|---|

| King of Spades | David |

| King of Hearts | Charles (possibly Charlemagne, or Charles VII, in which case Rachel (see below) would be the pseudonym of his mistress, Agnès Sorel) |

| King of Diamonds | Julius Caesar |

| King of Clubs | Alexander the Great |

| Queen of Spades | Pallas |

| Queen of Hearts | Judith |

| Queen of Diamonds | Rachel (either biblical, historical (see Charles above), or mythical as a corruption of the Celtic Ragnel, relating to Lancelot below) |

| Queen of Clubs | Argine (possibly an anagram of regina, which is Latin for queen, or perhaps Argea, wife of Polybus and mother of Argus) |

| Knave of Spades | Ogier the Dane/Holger Danske (a knight of Charlemagne) |

| Knave of Hearts | La Hire (comrade-in-arms to Joan of Arc, and member of Charles VII's court) |

| Knave of Diamonds | Hector |

| Knave of Clubs | Judas Maccabeus, or Lancelot |

تغيير التصميم في وقت لاحق

الرمزية

الحالي

مقالة مفصلة: Standard 52-card deck

مقالة مفصلة: Standard 52-card deck

التصميم الفرنسي

روسيا

شرق آسيا

منغوليا

الهند

Accessible playing cards

الرموز في اليونيكود

تقنيات الإنتاج

انظر أيضاً

|

مشاع المعرفة فيه ميديا متعلقة بموضوع أوراق اللعب. |

الهوامش

- ^ Pang, Kevin (April 21, 2015). "72 Hours Inside the Eye-Popping World of Cardistry". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Cepeda, Esther (July 26, 2019). "Cardistry transforms deck of cards into performance art". Post Independent. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Klimek, Chris (November 30, 2018). "Ricky Jay Remembered, From The Wings: An Assistant's Thoughts On the Late Magician". NPR. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

The second act climaxed with him throwing cards into watermelon, first the squishy interior, then the "pachydermatic outer melon layer."

- ^ Hochman, Gene; Dawson, Tom; Dawson, Judy (2000). The Hochman Encyclopedia of American Playing Cards. Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems. ISBN 1572812974. OCLC 44732377.

- ^ Pattern Sheet 80 at i-p-c-s.org. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Decker, Depaulis & Dummett 1996, p. ix.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkaplan-nyt-2016 - ^ Wong, Alex (April 4, 2019). "How young magicians are learning to cast a spell on a modern audience". National Post. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Mallonee, Laura (November 9, 2018). "The Secret Tools Magicians Use to Fool You". Wired. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Hegel, Theresa (January 10, 2018). "Smart Promotional Items at CES". Advertising Specialty Institute. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Sawyer, Miranda (June 2, 2019). "'The public has a right to art': the radical joy of Keith Haring". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

His art is everywhere. There are Haring T-shirts, Haring shoes, Haring chairs. You can buy Haring baseball hats and badges and baby-carriers and playing cards and stickers and keyrings.

- ^ Wilson, Lexi (December 1, 2018). "A new deck of cards with a Bakersfield twist". Bakersfield Now. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Xinhua (2019-05-17). "Shanghai uses playing cards to promote garbage sorting". China Daily. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnbc-ap-columbia - ^ Stack Commerce (January 16, 2018). "These playing cards help you learn about design". Popular Science. Archived from the original on July 29, 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Ramzi, Lilah (February 25, 2019). "All Dressed Up and Nowhere to Go: The Best Looks to Wear at Home". Vogue. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

Tiffany & Co. playing cards, $115

- ^ Seideman, David (January 18, 2019). "Trading Cards Continue To Trounce The S&P 500 As Alternative Investments". Forbes. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Sullivan, Paul (March 23, 2018). "Trading Cards: A Hobby That Became a Multimillion-Dollar Investment". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Needham 1954, pp. 131–132.

- ^ أ ب Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards". American Anthropologist. VIII (1): 61–78. doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070.

- ^ أ ب ت Lo, A. (2009). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 389–406. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466. S2CID 159872810.

- ^ Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- ^ Needham 2004, p. 332 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- ^ "Works titled 杜陽雜編". Chinese Text Project. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich (2012-09-30). "Duyang zabian". ChinaKnowledge.de: An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Lo, Andrew (2000). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 389–406. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466. S2CID 159872810 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Parlett, David. "Chinese Leaf Game: Did the Chinese really invent card games?". Historic Card Games. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ Zhou, Songfang (1997). "On the Story of Late Tang Poet Li He". Journal of the Graduates Sun Yat-sen University. 18 (3): 31–35.

- ^ Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 131.

- ^ أ ب Needham 2004, p. 329.

- ^ أ ب ت Parlett, David, "The Chinese "Leaf" Game", March 2015.

- ^ Lo, Andrew. (2000). The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 63(3), 389–406.

- ^ Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 132.

- ^ Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- ^ Playing card basics at the International Playing-Card Society website

- ^ Needham & Tsien 1985, p. 307.

- ^ Nosowitz, Dan (13 July 2020). "Playing Cards Around the World and Through the Ages". Atlas Obscura (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Dummett 1980, p. 41.

- ^ Mayer, Leo Ary (1939), Le Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 38, pp. 113–118, http://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/38/, retrieved on 2008-09-08.

- ^ Berry, John (December 2001). "Mamluk Problems". The Playing-Card. The International Playing-Card Society. 30 (3): 139. ISSN 0305-2133.

- ^ Pollett, Andrea "The Playing-Card", Vol. 31, No 1 pp. 34–41.

- ^ Mamluk cards. Cards.old.no. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ^ Wintle, Simon. Moorish playing cards at The World of Playing Cards. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ The Mamluk Cards. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ^ No trump trick-taking games at pagat.com

المصادر

- Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking British Museum Press (in UK),2nd edn, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Hind, Arthur M. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- Lo, Andrew. "The Game of Leaves: An Inquiry into the Origin of Chinese Playing Cards," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 63, No. 3 (2000): 389-406.

- Needham, Joseph (2004), Science & Civilisation in China, V:1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05802-3

- Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-214165-1

- Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library MS Add. 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352

- Singer, Samuel Weller (1816), Researches into the History of Playing Cards, R. Triphook, http://books.google.com/?id=ZTMCAAAAYAAJ

وصلات خارجية

- History of the design of the court cards

- Courts on playing cards

- Deck of playing cards in SVG

- Deck of playing cards in .fla and .png

- The History of Playing Cards discussed in 1987 by Roger Somerville

- History of Playing Cards

- Brief History of Playing Cards by Tommy Stern

- World Web Playing Cards Museum

- History of playing cards

- The International Playing-Card Society

قالب:Playing card

قالب:Tarot Cards

قالب:Poker footer

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>