وليام گارستن

السير وليام إدموند گارستن Sir William E. Garstin, G.C.M.G., G.B.E (29 يناير 1849 - 8 يناير 1925)، مهندس مدني ومسئول استعماري بريطاني في مصر. كان النائب البريطاني لوزير الأشغال العامة المصري.

النشأة

وُلِد وليام گارستن في الهند في 29 يناير 1849، كثاني أبناء تشارلز گارستن، في الخدمة العامة للبنغال، وزوجته، أگنس هلن، ابنة و. مكنزي، العامل في شركة الهند الشرقية.[1]

Educated at Cheltenham College and King's College, London, he in 1872 entered the Indian Public Works Department. In 1885 he was invited by Sir Colin Scott Moncrieff, who had just taken charge of the Public Works Ministry in Egypt, to make one of the small group of Indian engineers who were undertaking the reorganisation of the irrigation system of Egypt, which was at that time in complete disorder.[2] In 1892 became Inspector-General of Irrigation in Egypt and Under-Secretary of State for Public Works. He was created K.C.M.G. in 1897 and G.C.M.G. in 1902, and in 1907 was appointed British Government director of the Suez Canal Company. During the World War he was engaged on Red Cross work in England, and was in 1918 created G.B.E.[3]

مهندس النيل

THE old Greek philosopher whose theory of the underlying principle of the universe was that "Allis water " might have pointed, were he alive to-day, to Egypt for at least a local justification. Water has been the supreme natural influence in that strange and historic country since the birth of civilisation to the present day ; but out of the five or six thousand years of Egyptian chronicles, it has been reserved to the last twenty or thirty to emphasise the truth of the aphorism that "the Nile is Egypt, and Egypt is the Nile" as it has never been emphasised before. And perhaps the Greek philosopher, seeking a broad, natural principle on which to explain all forms of growth and development, might have been likelier to forecast the results of British rule in Egypt than . the keenest modern student of political history. In Egyptian affairs one commanding figure, no doubt, has of late stood out pre-eminent in the person of the wise and patient Proconsul whose thirty years of public service in Egypt have added a lustre of their own to the annals of British administration. But, following Lord Cromer, another official has recently retired from service in Egypt whose record is as picturesque as it is far-reaching and permanent. Sir William Garstin, sixteen years ago appointed Inspector-General of Irrigation, and lately Adviser to the Egyptian Ministry of Public Works, sailed from Port Said on Monday after paying a round of farewell visits to his friends in the Delta provinces. His departure has been marked by address after address of gratitude for his services and grief at losing an official who was also a friend. Even the most imaginative of prophets might have hesitated, thirty years ago, to outline a picture such as the Times correspondent at Cairo drew on Tuesday. "Wherever the news of his coming had preceded him," we read, "crowds of fellaheen thronged by the lock-gates on the canals to wish well to the great engineer, the best years of whose life have been devoted to the welfare of Egypt." The source of that material welfare doubtless would be summed up by the crowding fellaheen in the barrage, the locks, and the canals. For the small farmer, dependent not on rain but on the river for moisture to fertilise his soil and quicken the seeds he sows, it is a perpetual truth that his all depends on water, and his gratitude to the man who has established and regularised its supply is as simple as it is deep.[4]

Sir William Garstin has made the study of irrigation, especially in Egypt, his life's work, and, given the genius to see what is required, and the money to carry out extensive schemes, there could be few more fascinating employments than the controlling and directing of huge volumes of water. It is a fascination which would be increased two- fold and threefold by dealing with a river which has the greatest place among the rivers of history, which in its upper stretches flows through forests and ravines hardly yet penetrated by man, and which wastes in hideous marshes and on useless plants millions of tons of water which might be used for the life and the food of mankind. To an engineer, too, there would be a strong attraction in the task of harnessing and employing the water of a river like the Nile, because of the extraordinary complexity of the problem involved. It is not a question of mere cutting of channels or erecting dams along the course of a single river, but of regulating the supply of water that is thrown into the main channel by half-a-dozen tributaries which flood and run dry at different times. Nor is it a question of controlling running water only, or even water only. Wind and flood-water together on the upper reaches of the Nile can combine to create conditions which might destroy the work of years in an

hour. Sir William Garstin has described (in the Nineteenth Century, September, 1905) the sight that he saw on the Bahr-el-Gebel, the name by which the White Nile goes

through the " sudd " area, at the beginning of the rainy season of 1900, when strong winds were blowing. The very marshes through which the great river ran began to move :-

"Hundreds of acres of apparently solid ground, covered with reeds, were set in motion by the action of the winds and water, and drifted about in the lagoons bordering the river, eventually breaking into its channel and blocking it. In a few hours time a solid mass was formed, consisting of earth and vegetation, several hundred yards in length and nearly twenty feet thick. This mass was so speedily compressed by the force of the confined water that it attained a solidity sufficient for an elephant to have crossed it with impunity. The sight of these drifting islands, and the resistless manner in which they forced their way into the river, and in which their masses piled one above the other, impressed me greatly."

It was the sight of these unstable marshes, and the realisation of the immense force of wind and water together, which, combined with other reasons, led Sir William Garstin to reject the idea of improving the channel of the Bahr-el-Gebel, and to try for another solution of the White Nile problem.

An engineer of long, and in some ways unique, experience would not recommend interfering with Nature on an extensive scale until an absolutely thorough study had been made of all conditions and data, and until the fullest amount of informa- tion had been collected. But Sir William Garstin, in the article from which we have quoted and in Blue-books, has given general reasons which have led him to advocate a particular way of dealing with the waters of the White Nile, so as to bring into use a larger volume of water for Egypt, leaving the Blue Nile and its tributary rivers to supply the wants of the Soudan. The Blue Nile and the White join at Khartoum, and the problems connected with extending irriga- tion from the Blue Nile, although possibly expensive, are fairly - simple. But the problem of the White Nile is immense.

The White Nile north of the Albert Nyanza and the Victoria Nyanza, which is its source, tumbles a broad stream of sparkling water, fed by leaping cascades, for the first quarter of its length. Then, at Gondokoro, it enters the marshes, and at Bor, a hundred miles further north, turns to the north-west, and struggles in an ocean of reeds, papyrus, and mud, described by the late Sir Samuel Baker as "a heaven for mosquitos and a damp hell for men." This is the " sudd" country, from which, only a few years ago, were removed those remarkable barriers of weed which used to block the river completely ; and it is in the swamps and lagoons of this enormous area of marshland that the White Nile loses actually from fifty to eighty-five per cent, of the water which is brought down from the Albert Nyanza and the hills. It is the prevention of this waste of water by flooding and evaporation which is the great problem of the White Nile, and the remedy which Sir William Garstin has suggested is direct and simple. He rejects the idea of deepening and widening the existing channel, or, rather, channels, for there are two, known as the Bahr-el-Gebel and the Bahr-el-Zaraf, and he has proposed instead a new channel, cut due north through dry land from Bor, where the river turn, west into the marshes, to the junction with the Sobat River, where it has turned east again and left them. This "new cut" would be controlled by two masonry regulators, one of which would be used to divert all water wanted for Egypt away from the marshes direct into the northern channel, and the other would, when necessary, turn any flood-water which was not wanted into the marshes to evaporate.

If this channel were cut, the extra supply of summer water

would admit of a great extension of perennial irrigation throughout Egypt, and also, by freeing the resources of the Blue Nile, throughout the Soudan. The difficulty, of course, would be the expense, and for some time, no doubt, that

difficulty will remain. . The present policy of the Egyptian Government is an extension of communications, and increased facilities for irrigation will follow. But whatever plan be eventually adopted for dealing with the Nile, White or Blue. there will be no weakening of the tribute paid to the memory of the brilliant engineer who, under the beneficent band of Egypt's greatest Governor, has been able to leave behind him, truly more enduring than brass, a monument in water.

سد أسوان

معرض الصور

معرض صور

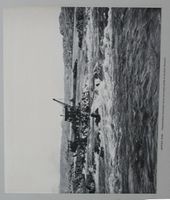

هويس في خزان أسوان.

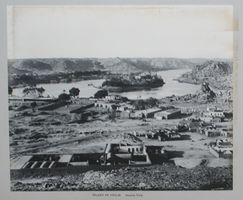

جزيرة فيلة: منظر عام

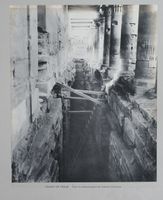

جزيرة فيلة: أساسات بهو الأعمدة الشرقي.

قناطر أسيوط: الأساسات دق خوازيق من الحديد الزهر.

دراسة بحر الجبل، ع1890

مقالة مفصلة: بحر الجبل

مقالة مفصلة: بحر الجبل

ترأس السير وليام گارستن فريقاً لدراسة مجرى بحر الجبل فيما بين نيمولي ورجاف، الذي يبلغ طوله حوالي 156 كيلومترا. والمفهوم أن مجرى النهر يدخل في هذا القطاع منطقة الشلالات فولا على مسافة حوالي 7 كيلومترات شمال موقع نيمولي. وعندئذ يضيق المجرى إلى حوالي 60 مترا. ويتدافع الماء الجاري على الجنادل، وينحدر انحدارا شديدا حتى يضيق وتصبح جوانبه الصلبة متقاربة، ولايفصل بينهما أكثر من ست عشرة مترا.

وهكذا يبدو المجرى الضيق حديث المنشأ من وجهة النظر الجيولوجية. كما أن شكله المستقيم إلى حد كبير يوحي بالانكسار أو التصدع الذي تمخض عن هذا الجريان السريع الجياش المتدفق فيما بين نيمولي ورجاف. وتبدو صورة الأرض على جانبي المجرى في هذا القطاع وعرة خشنة مضرسة. وترتفع الأرض على الجانب الشرقي للنهر بشكل واضح وسريع، إلى منسوب حوالي 1000 متر. وتبدو في الصورة على شكل هضبة مرتفعة تعلوها الجبال المنفردة، المتناثرة على أنحاء سطحها في نظام غير رتيب. وتظهر على الجانب الشرقي أيضا مرتفعات وجبال كجبل لاتوكا وجبل لانجيا الشامخة . ولعلها تعبر تعبيرا صادقا عن صورة من صور النشاط البركاني الحديث في منطقة الضعف القشري، الذي ترتب على الانكسار، أو التصدع الذي أشرنا إليه.

ويذكر السير وليام گارستن أن هناك سلسلة أو مجموعات من الجنادل، التي تعترض الجريان في مجرى النهر فيما بعد فولا. وتشمل هذه السلسلة مدافع يوربورا وتشمل هذه السلسلة مدافع يربورا Yerbora على مسافة حوالي 50 كيلومترا من موقع نيمولي، وجنادل جوجي Gouji التي تظهر في المجرى بعد حوالي 20 كيلومترا من مدافع يوربورا، وتحتل حوالي 15 كيلومترا من حيز النهر الجياش. كما تظهر في حيز المجرى جنادل مكيدو، وتحتل خمسة كيلو مترات متوالية، ثم جنادل بدن Bedden جنوب رجاف مباشرة، ومهما يكن من أمر هذه الصورة الورعة فإن سمات النهر وصفات الجنادل وارتباط نشأتها بعوامل باطنية وما تعبر عنه من حيث حداثة النهر عن وجهة النظر الجيولوجية، تتطلب تفسيرا وإيضاحا.

رفضه مشروع هرتزل في سيناء، 1903

مقالة مفصلة: مشروع هرتزل في سيناء

مقالة مفصلة: مشروع هرتزل في سيناء

تقدم تيودور هرتزل بمشروع الاتفاقية التي أراد بها التعاقد مع الحكومة المصرية للحصول على امتياز الاستيطان في شبه جزيرة سيناء وكان ملخصها كالتالي:

- أولاً: تمنح الحكومة المصرية هرتزل أو الشركة التي يؤسسها الحق في استعمار المستوطنة بعقد امتياز لمدة 99 عاما.

- ثانياً: تتعهد الحكومة المصرية بتوصل المياه إلى سيناء.

- ثالثاً: بالنسبة للمثلث الجنوبي لا تتصرف فيه الحكومة إلا بالتشاور مع الإدارة الصهيونية للمستوطنة.

وربط كرومر موافقته برد وكيل نظارة الأشغال السير وليام جارستن، الذي جاء رده في 5 مايو 1903 بالرفض بناء على الآتي:

- صعوبة نقل المياة من خلال 8 أنابيب قطر كل منها متران في هذا الوقت لأسباب فنية.

- التأثير السلبي للمشروع على مشروعات الزراعة المصرية بالوادي، خاصة محصول القطن الحيوي للصناعة الإنجليزية.

تعلل كرومر بمذكرة جارستن لكن هناك أسبابا أخرى جعلت الإنجليز يجمدون المشروع، منها الاستعداد للحرب العالمية الأولى والتوافق بين إنجلترا وفرنسا على تقسيم تركة الدولة العثمانية ومنها فلسطين.

قناة جونقلي

صاغ السير وليام گارستن، أول مقترح مفصل لحفر قناة جونقلي شرق السـُد في 1907.[5] By bypassing the swamps, evaporation of the Nile's water would vastly decrease, allowing an increase in the area of cultivatable land in Egypt by 8100 km2 (2000000 acre).

كتاباته

- أعمال خزانات النيل في أسوان وأسيوط.[6]

التكريم

- الحية العملاقة، جيگانتوفيس Gigantophis، سُميت لدى اكتشاف حفريتها، في 1901، بإسم garstini تكريماً للسير وليام گارستن.

الهامش

- ^ Elizabeth Baigent. "Garstin, Sir William Edmund". قاموس أكسفورد للسير الوطنية.

- ^ H.G.L. (1925-01-17). "Sir William E. Garstin, G.C.M.G., G.B.E". نيتشر.

- ^ "Sir William Edmund Garstin". theodora.com. 2018-09-29.

- ^ "AN ENGINEER OF THE NILE". سپكتيتر. 1908-04-25. p. 25.

- ^ "The Egyptian Sudan, its history and monuments". archive.org. 1907.

- ^ Garstin, William; George, D.S. (1902). "The Nile Reservoir Works at Aswan and Asyut". وزارة الري المصرية.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)