معاهدة غوادالوبى-هيدالغو

| Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the Republic of Mexico | |

|---|---|

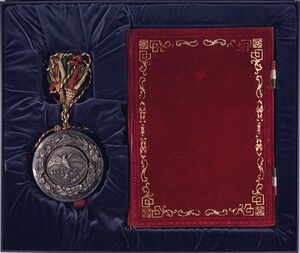

Cover of the exchange copy of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo | |

| وُقـِّعت | 2 فبراير 1848 |

| المكان | Guadalupe Hidalgo |

| سارية منذ | 30 May 1848 |

| المفاوضون | قائمة

|

| الأطراف | |

| ذِكر | 9 Stat. 922; TS 207; 9 Bevans 791 |

| See also the military convention of 29 February 1848 (5 Miller 407; 9 Bevans 807). | |

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| التشيكانو والأمريكان المكسيكيين |

|---|

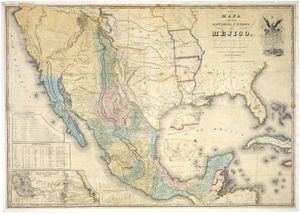

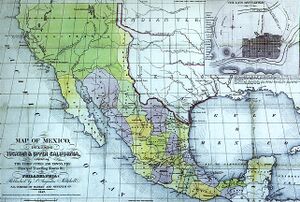

معاهدة گوادالوپى هيدالگو (Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo؛ Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo بالاسبانية) وقعتها الولايات المتحدة والمكسيك في الثاني من فبراير 1848م. وقد أنهت هذه المعاهدة رسميًا الحرب المكسيكية (1846 – 1848م) التي اندلعت بسبب وضع تكساس، ومنازعات أخرى حول الأراضي. وانعقدت المفاوضات في ڤيلا دى گوادالوپى-هيدالگو وهي بلدة صغيرة تُشكل الآن جزءًا من مدينة مكسيكو سيتي. وبموجب هذه المعاهدة حصلت الولايات المتحدة على الأراضي التي تؤلف الآن ولايات كاليفورنيا ونيفادا ويوتا، ومعظم نيومكسيكو وأريزونا، وأجزاء من كولورادو ووايومنگ. واعتبر نهر ريو جراندي الحد الفاصل بين تكساس والمكسيك. ووافقت الولايات المتحدة على أن تدفع للمكسيك مبلغ 15 مليون دولار أمريكي، وأن تتولى سداد جميع المطالب السابقة التي رفعها المواطنون الأمريكيون ضد المكسيك بحد أقصى قدره 3,250,000 دولار أمريكي.

المفاوضات

Nicholas Trist negotiated the peace talks; Trist, the chief clerk of the U.S. State Department, accompanied General Winfield Scott as a diplomat and President James K. Polk's representative. After two previous unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a treaty with General José Joaquín de Herrera, Trist and General Scott determined that the only way to deal with Mexico was as a conquered enemy. Trist negotiated with a special commission representing the collapsed government led by Don José Bernardo Couto, Don Miguel de Atristain, and Don Luis Gonzaga Cuevas of Mexico.[1]

البنود

Although Mexico ceded Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México, the text of the treaty[2] did not list territories to be ceded and avoided the disputed issues that were causes of war: the validity of the 1836 revolution that established the Republic of Texas, Texas's boundary claims as far as the Rio Grande, and the right of the Republic of Texas to arrange the 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States.

Instead, Article V of the treaty described the new U.S.–Mexico border. From east to west, the border consisted of the Rio Grande northwest from its mouth to the point where it strikes the southern boundary of New Mexico (roughly 32 degrees north), as shown in the Disturnell map, then due west from this point to the 110th meridian west, then north along the 110th meridian to the Gila River and down the river to its mouth. Unlike the New Mexico segment of the boundary, which depended partly on unknown geography, "to preclude all difficulty in tracing upon the ground the limit separating Upper from Lower California", a straight line was drawn from the mouth of the Gila to one marine league south of the southernmost point of the port of San Diego, slightly north of the previous Mexican provincial boundary at Playas de Rosarito.

Comparing the boundary in the Adams–Onís Treaty to the Guadalupe Hidalgo boundary, Mexico conceded about 55% of its pre-war, pre-Texas territorial claims[3] and now has an area of 1,972,550 km² (761,606 sq mi).

In the United States, the 1.36 million km² (525,000 square miles) of the area between the Adams-Onis and Guadalupe Hidalgo boundaries outside the 1،007،935 km2 (389،166 sq mi) claimed by the Republic of Texas is known as the Mexican Cession. That is to say, the Mexican Cession is construed not to include any territory east of the Rio Grande, while the territorial claims of the Republic of Texas included no territory west of the Rio Grande. The Mexican Cession included essentially the entirety of the former Mexican territory of Alta California, but only the western portion of Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico, and includes all of present-day California, Nevada and Utah, most of Arizona, and western portions of New Mexico and Colorado.

Articles VIII and IX ensured the safety of existing property rights of Mexican citizens living in the transferred territories. Despite assurances to the contrary, the property rights of Mexican citizens were often not honored by the United States in accordance with modifications to and interpretations of the Treaty.[4][5][6] The United States also agreed to assume $3.25 million (equivalent to $87.3 million today) in debts that Mexico owed to United States citizens.

The residents had one year to choose whether they wanted American or Mexican citizenship; over 90% chose American citizenship. The others moved to what remained of Mexico (where they received land) or, in some cases in New Mexico, were allowed to remain in place as Mexican citizens.[7][8]

Article XII engaged the United States to pay, "In consideration of the extension acquired", 15 million dollars (equivalent to $400 million today),[9] in annual installments of 3 million dollars.

Article XI of the treaty was important to Mexico. It provided that the United States would prevent and punish raids by Indians into Mexico, prohibited Americans from acquiring property, including livestock, taken by the Indians in those raids, and stated that the United States would return captives of the Indians to Mexico. Mexicans believed that the United States had encouraged and assisted the Comanche and Apache raids that had devastated northern Mexico in the years before the war. This article promised relief to them.[10]

Article XI, however, proved unenforceable. Destructive Indian raids continued despite a heavy U.S. presence near the Mexican border. Mexico filed 366 claims with the U.S. government for damages done by Comanche and Apache raids between 1848 and 1853.[11] In 1853, in the Treaty of Mesilla concluding the Gadsden Purchase, Article XI was annulled.[12]

اندلاع الحرب

U.S. forces quickly moved beyond Texas to conquer Alta California, and New Mexico. Fighting there ended on 13 January 1847 with the signing of the "Capitulation Agreement" at "Campo de Cahuenga" and the end of the Taos Revolt.[13] By the middle of September 1847, U.S. forces had successfully invaded central Mexico and occupied Mexico City.

مفاوضات السلام

Some Eastern Democrats called for complete annexation of Mexico and recalled that a group of Mexico's leading citizens had invited General Winfield Scott to become dictator of Mexico after his capture of Mexico City (he declined). [14] However, the movement did not draw widespread support. President Polk's State of the Union address in December 1847 upheld Mexican independence and argued at length that occupation and any further military operations in Mexico were aimed at securing a treaty ceding California and New Mexico up to approximately the 32nd parallel north and possibly Baja California and transit rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[15]

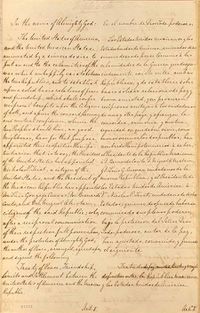

تعديلات على المعاهدة والتصديق عليها

The version of the treaty ratified by the United States Senate eliminated Article X,[17] which stated that the U.S. government would honor and guarantee all land grants awarded in lands ceded to the United States by those respective governments to citizens of Spain and Mexico. Article VIII guaranteed that Mexicans who remained more than one year in the ceded lands would automatically become full-fledged United States citizens (or they could declare their intention of remaining Mexican citizens); however, the Senate modified Article IX, changing the first paragraph and excluding the last two. Among the changes was that Mexican citizens would "be admitted at the proper time (to be judged of by the Congress of the United States)" instead of "admitted as soon as possible", as negotiated between Trist and the Mexican delegation.

An amendment by Jefferson Davis giving the United States most of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León, all of Coahuila, and a large part of Chihuahua was supported by both senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party, Thomas Hart Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray Mason of Virginia and Ambrose Hundley Sevier were opposed, and the amendment was defeated 44–11.[18]

An amendment by Whig Sen. George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico and California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats. Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding votes for acquiring the new territories.

A motion to insert into the treaty the Wilmot Proviso (banning slavery from the acquired territories) failed 15–38 on sectional lines.

The treaty was leaked to John Nugent before the U.S. Senate could approve it. Nugent published his article in the New York Herald and, afterward, was questioned by senators. He was detained in a Senate committee room for one month, though he continued to file articles for his newspaper and ate and slept at the home of the sergeant of arms. Nugent did not reveal his source, and senators eventually gave up their efforts.[19]

The treaty was subsequently ratified by the U.S. Senate by a vote of 38 to 14 on 10 March 1848 and by Mexico through a legislative vote of 51 to 34 and a Senate vote of 33 to 4, on 19 May 1848. News that New Mexico's legislative assembly had just passed an act for the organization of a U.S. territorial government helped ease Mexican concern about abandoning the people of New Mexico.[20] The treaty was formally proclaimed on 4 July 1848.[21]

پروتوكول كوِريتارو

On 30 May 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further negotiated a three-article protocol to explain the amendments. The first article stated that the original Article IX of the treaty, although replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy of land grants pursuant to Mexican law.[22]

The protocol further noted that the Mexican Minister of Foreign Affairs had accepted said explanations on behalf of the Mexican Government,[22] and was signed in Querétaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford and Luis de la Rosa.

The United States would later ignore the protocol on the grounds that the U.S. representatives had over-reached their authority in agreeing to it.[23]

معاهدة مسيا

The Treaty of Mesilla, which concluded the Gadsden purchase of 1854, had significant implications for the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article II of the treaty annulled article XI of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and article IV further annulled articles VI and VII of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Article V, however, reaffirmed the property guarantees of Guadalupe Hidalgo, specifically those contained within articles VIII and IX.[24]

الآثار المترتبة عليها

In addition to the sale of land, the treaty also provided recognition of the Rio Grande as the boundary between the state of Texas and Mexico.[25] The land boundaries were established by a survey team of appointed Mexican and American representatives,[26] and published in three volumes as The United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. On 30 December 1853, the countries, by agreement, altered the border from the initial one by increasing the number of border markers from 6 to 53.[26] Most of these markers were simply piles of stones.[26] Two later conventions, in 1882 and 1889, further clarified the boundaries, as some of the markers had been moved or destroyed.[26] Photographers were brought in to document the location of the markers. These photographs are in Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief Engineers, in the National Archives.

The southern border of California was designated as a line from the junction of the Colorado and Gila rivers westward to the Pacific Ocean so that it passes one Spanish league south of the southernmost portion of San Diego Bay. This was done to ensure that the United States received San Diego and its excellent natural harbor.[27]

The treaty extended the choice of U.S. citizenship to Mexicans in the newly purchased territories before many African Americans, Asians, and Native Americans were eligible. If they chose to, they had to declare to the U.S. government within a year of the Treaty being signed; otherwise, they could remain Mexican citizens, but they would have to relocate.[3] Between 1850 and 1920, the U.S. Census counted most Mexicans as racially "white".[28]

Community property rights in California and other western states are based on the Visigothic Code which Spain adopted and then brought to the Americas, including the former territories of Mexico that were ceded to the U.S. Although each state had different motivations for adopting the Spanish approach, one common driver was that it was already in place in the region for many years. Changing to a common law system for marital property "would have been nothing short of a revolution".[29]

الأراضي التي اكتسبتها الولايات المتحدة

The United States received the territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. Today they comprise some or all of the U.S. states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming from the treaty.

قضايا إضافية

Disputes about whether to make all this new territory into free states or slave states contributed heavily to the rise in North–South tensions that led to the American Civil War just over a decade later.

Border disputes continued. Mexico's economic problems persisted,[30] leading to the controversial Gadsden Purchase in 1854, intended to rectify an error in the original treaty, but led to Mexico demanding a large sum of money for the revision, which was paid. There was also William Walker's short-lived Republic of Lower California filibustering incident in that same year.[31] The Channel Islands of California and Farallon Islands are not mentioned in the Treaty.[32]

The armed forces of both countries routinely crossed the border. Mexican and Confederate troops often clashed during the American Civil War, and the United States crossed the border during the war of Second French intervention in Mexico. In March 1916, Pancho Villa led a raid on the U.S. border town of Columbus, New Mexico, which was followed by the Pershing expedition. The shifting of the Rio Grande since the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe caused a dispute over the boundary between the states of New Mexico and Texas, a case referred to as the Country Club Dispute that was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927.[33] Controversy over community land grant claims in New Mexico persists to this day.[34]

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo led to the establishment in 1889 of the International Boundary and Water Commission to maintain the border and, according to newer treaties, to allocate river waters between the two nations and to provide for flood control and water sanitation. Once viewed as a model of international cooperation, in recent decades, the IBWC has been heavily criticized as an institutional anachronism, bypassed by modern social, environmental, and political issues.[35]

Writing many years later, Nicholas Trist would describe the treaty as "a thing for every right-minded American to be ashamed of".[36]

انظر أيضًا

- الحرب المكسيكية

- شراء گادسدن

- Treaty of Cahuenga

- United States and Mexican Boundary Survey

- 1848 في المكسيك

- Annexation Bill of 1866

- United States Court of Private Land Claims

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (History of New Mexico)

- Land Grants (Mexican period of Arizona)

- Californios in literature

الهامش

- ^ Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War, by author Wallace Ohrt

- ^ "Avalon Project – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848". Avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ أ ب "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- ^ U.S. Congress. Recommendation of the Public Land Commission for Legislation as to Private Land Claims, 46th Congress, 2nd Session, 1880, House Executive Document 46, pp. 1116–17.

- ^ Gonzales, Manuel G. (2009). Mexicanos: A history of Mexicans in the United States (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-253-33520-3.

- ^ Davenport (2005), p. 48.

- ^ Noel, Linda C. (2011). "'I am an American': Anglos, Mexicans, Nativos, and the National Debate over Arizona and New Mexico Statehood". Pacific Historical Review. 80 (3): 430–467 [at p. 436]. doi:10.1525/phr.2011.80.3.430.

- ^ Griswold del Castillo, Richard (1990). "Citizenship and Property Rights: U.S. Interpretations of the Treaty". The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 62-86. ISBN 0-8061-2240-4.

- ^ "Error -- File Not Found (Hispanic Reading Room, Hispanic Division, Area Studies)". loc.gov.

- ^ Delay, Brian (2007). "Independent Indians and the U.S. Mexican War". The American Historical Review. 112 (1): 67. doi:10.1086/ahr.112.1.35.

- ^ Schmal, John P. "Sonora: Four Centuries of Indigenous Resistance". Houston Institute of Culture. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Kluger, Richard (2007). Seizing Destiny: How America Grew From Sea to Shining Sea. New York: Knopf. pp. 493–494. ISBN 978-0-375-41341-4.

- ^ Original Capitulation Agreement document (one of 25) on view at Campo de Cahuenga historical site

- ^ "Mexican Argument for Annexation." The Living Age, Volume 10, Issue 123. 19 September 1846.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPolk Third Annual Message - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLOC-TGH - ^ "The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo." Library of Congress, Hispanic Reading Room. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ George Lockhart Rives (1913). The United States and Mexico, 1821–1848. C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 634–636.

- ^ "The Senate Arrests a Reporter". U.S. Senate.

- ^ Rives 1913, p. 649.

- ^ Online Highways LLC editorial group. "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". U-S-History.com. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ^ أ ب Treaty of Hidalgo, Protocol of Querétaro. From: academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ David Hunter Miller, Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America, vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1937)

- ^ Mills, B. p. 122.

- ^ Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Article V. From: academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةarchives - ^ Davenport 2004.

- ^ Gibson, C.J. and E. Lennon. 1999. "Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1850–1990." U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Retrieved 6 November 2007.

- ^ Newcombe, Caroline Bermeo (2011). "The Origin and Civil Law Foundation of the Community Property System, Why California Adopted It and Why Community Property Principles Benefit Women". University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class. 11 (1).

- ^ Davenport (2005), p. 60.

- ^ Wyllys 1933.

- ^ Barnard R. Thompson. "Mexico's Claim to California Islands – A Never-ending Story".

- ^ Bowden, J. J. (1959). "The Texas-New Mexico Boundary Dispute along the Rio Grande". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 63 (2): 221–237. JSTOR 30240862.

- ^ "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: Findings and Possible Options Regarding Longstanding Community Land Grant Claims in New Mexico" (PDF). General Accounting Office. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- ^ Robert J. McCarthy, Executive Authority, Adaptive Treaty Interpretation, and the International Boundary and Water Commission, U.S.-Mexico, 14-2 U. Denv. Water L. Rev. 197(Spring 2011) (also available for free download at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1839903).

- ^ Morgan, Robert (21 August 2012). Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion. North Carolina: Algonquin Books. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-61620-189-0.

الهامش

- Griswold del Castillo, Richard. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. University of Oklahoma Press, 1990

- Ohrt, Wallace. Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War Texas A&M University Press, 1997

- Jesse S. Reeves, "The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo", The American Historical Review, 10 (Jan. 1905), 309-324, full text online at JSTOR

وصلات خارجية

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and related resources at the U.S. Library of Congress

- Text of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

- Copy of Treaty, including sections stricken out by Senate

- Text of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and anaysis

- U.S. General Accounting Office report on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, June 2004

- Library of Congress Guide to the Mexican War

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- 1848 في المكسيك

- 1848 في القانون

- تاريخ أريزونا

- تاريخ كاليفورنيا

- تاريخ كولورادو

- تاريخ نـِڤادا

- تاريخ نيو مكسيكو

- تاريخ توسع الولايات المتحدة

- تاريخ يوتا

- تاريخ وايومنگ

- معاهدات الحرب الأمريكية المكسيكية

- التاريخ الأمريكي المكسيكي

- معاهدات الولايات المتحدة

- معاهدات المكسيك

- معاهدات تضمنت تغييرات إقليمية

- حدود الولايات المتحدة

- حدود المكسيك

- النزاعات الحدودية لتكساس