مشروب غازي

المشروبات الغازية soft drink، هي مشروب غير كحولي يحتوي على مياه فوارة، مواد تحلية، ومواد منكهة. ويمكن أن تكون المحليات سكر، شراب ذرة عالي الفركتوز، أو بديل السكر (في حالة المشروبات منخفضة السعرات). ويمكن أن يحتوي المشروب الغازي أيضا على كافيين أو عصير فاكهة.

ولا تعتبر مشروبات الطاقة والعصائر الطبيعية من المشروبات الغازية. وكذلك لا تعتبر الشيكولاتة الساخنة، الشاي المثلج، القهوة، الحليب، الميلك شيك من المشروبات الغازية.

ويمكن أن تحتوي المشروبات الغازية على مقادير قليلة من الكحول، لكن يجب ألا يزيد محتوى الكحول عن 0.5% من إجمالي حجم المشروب[1][2] هذا اذا كان مشروب غير كحولي.[3]

وتنتشر المشروبات الغازية بنكهات مختلفة مثل الكولا، الليمون، الشعير، البرتقال، العنب، الڤانيليا، المياه المنكهة. وتشرب المشروبات الغازية باردة أو في درجة حرارة الغرفة.

التاريخ

The origins of soft drinks lie in the development of fruit-flavored drinks. In the medieval Middle East, a variety of fruit-flavored soft drinks were widely drunk, such as sharbat, and were often sweetened with ingredients such as sugar, syrup and honey. Other common ingredients included lemon, apple, pomegranate, tamarind, jujube, sumac, musk, mint and ice. Middle Eastern drinks later became popular in medieval Europe, where the word "syrup" was derived from Arabic.[4] In Tudor England, 'water imperial' was widely drunk; it was a sweetened drink with lemon flavor and containing cream of tartar. 'Manays Cryste' was a sweetened cordial flavored with rosewater, violets or cinnamon.[5]

Another early type of soft drink was lemonade, made of water and lemon juice sweetened with honey, but without carbonated water. The Compagnie des Limonadiers of Paris was granted a monopoly for the sale of lemonade soft drinks in 1676. Vendors carried tanks of lemonade on their backs and dispensed cups of the soft drink to Parisians.[6]

المشاريب الغازية

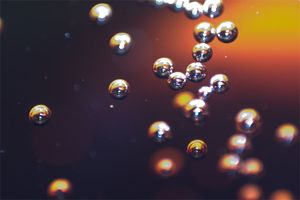

Carbonated drinks or fizzy drinks are beverages that contain dissolved carbon dioxide in carbonated water. The dissolution of CO2 in a liquid, gives rise to effervescence or fizz. Carbon dioxide is only weakly soluble in water; therefore, it separates into a gas when the pressure is released. The process usually involves injecting carbon dioxide under high pressure. When the pressure is removed, the carbon dioxide is released from the solution as small bubbles, which causes the solution to become effervescent, or fizzy.

Carbonated beverages are prepared by mixing chilled flavored syrup with chilled carbonated water. Carbonation levels range up to 5 volumes of CO2 per liquid volume. Ginger ale, colas, and related drinks are carbonated with 3.5 volumes. Other drinks, often fruity ones, are carbonated less.[7]

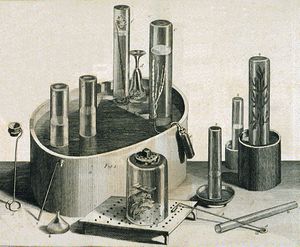

In the late 18th century, scientists made important progress in replicating naturally carbonated mineral waters. In 1767, Englishman Joseph Priestley first discovered a method of infusing water with carbon dioxide to make carbonated water[8] when he suspended a bowl of distilled water above a beer vat at a local brewery in Leeds, England. His invention of carbonated water (later known as soda water, for the use of soda powders in its commercial manufacture) is the major and defining component of most soft drinks.[9]

Priestley found that water treated in this manner had a pleasant taste, and he offered it to his friends as a refreshing drink. In 1772, Priestley published a paper entitled Impregnating Water with Fixed Air in which he describes dripping oil of vitriol (or sulfuric acid as it is now called) onto chalk to produce carbon dioxide gas and encouraging the gas to dissolve into an agitated bowl of water.[9]

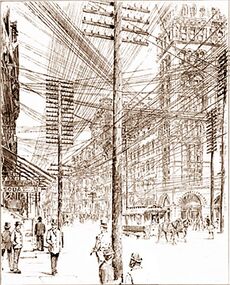

"The great soda-water shake up" (October 2014) The Atlantic.[10]

Another Englishman, John Mervin Nooth, improved Priestley's design and sold his apparatus for commercial use in pharmacies. Swedish chemist Torbern Bergman invented a generating apparatus that made carbonated water from chalk by the use of sulfuric acid. Bergman's apparatus allowed imitation mineral water to be produced in large amounts. Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius started to add flavors (spices, juices, and wine) to carbonated water in the late eighteenth century. Thomas Henry, an apothecary from Manchester, was the first to sell artificial mineral water to the general public for medicinal purposes, beginning in the 1770s. His recipe for 'Bewley's Mephitic Julep' consisted of 3 drachms of fossil alkali to a quart of water, and the manufacture had to 'throw in streams of fixed air until all the alkaline taste is destroyed'.[5]

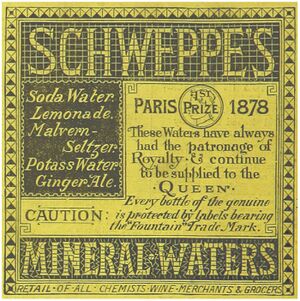

Johann Jacob Schweppe developed a process to manufacture bottled carbonated mineral water.[10] He founded the Schweppes Company in Geneva in 1783 to sell carbonated water,[11] and relocated his business to London in 1792. His drink soon gained in popularity; among his newfound patrons was Erasmus Darwin. In 1843, the Schweppes company commercialized Malvern Water at the Holywell Spring in the Malvern Hills, and received a royal warrant from King William IV.[12]

It was not long before flavoring was combined with carbonated water. The earliest reference to carbonated ginger beer is in a Practical Treatise on Brewing. published in 1809. The drinking of either natural or artificial mineral water was considered at the time to be a healthy practice, and was promoted by advocates of temperance. Pharmacists selling mineral waters began to add herbs and chemicals to unflavored mineral water. They used birch bark (see birch beer), dandelion, sarsaparilla root, fruit extracts, and other substances.

صودا الفوسفات

A variant of soda in the United States called "phosphate soda" appeared in the late 1870s. It became one of the most popular soda fountain drinks from 1900 through the 1930s, with the lemon or orange phosphate being the most basic. The drink consists of 1 US fl oz (30 ml) fruit syrup, 1/2 teaspoon of phosphoric acid, and enough carbonated water and ice to fill a glass. This drink was commonly served in pharmacies.[13]

سوق الجملة والتصنيع

Soft drinks soon outgrew their origins in the medical world and became a widely consumed product, available cheaply for the masses. By the 1840s, there were more than fifty soft drink manufacturers in London, an increase from just ten in the 1820s.[14] Carbonated lemonade was widely available in British refreshment stalls in 1833,[14] and in 1845, R. White's Lemonade went on sale in the UK.[15] For the Great Exhibition of 1851 held at Hyde Park in London, Schweppes was designated the official drink supplier and sold over a million bottles of lemonade, ginger beer, Seltzer water and soda-water.[14] There was a Schweppes soda water fountain, situated directly at the entrance to the exhibition.[5]

Mixer drinks became popular in the second half of the century. Tonic water was originally quinine added to water as a prophylactic against malaria and was consumed by British officials stationed in the tropical areas of South Asia and Africa. As the quinine powder was so bitter people began mixing the powder with soda and sugar, and a basic tonic water was created. The first commercial tonic water was produced in 1858.[16] The mixed drink gin and tonic also originated in British colonial India, when the British population would mix their medicinal quinine tonic with gin.[5]

A persistent problem in the soft drinks industry was the lack of an effective sealing of the bottles. Carbonated drink bottles are under great pressure from the gas, so inventors tried to find the best way to prevent the carbon dioxide or bubbles from escaping. The bottles could also explode if the pressure was too great. Hiram Codd devised a patented bottling machine while working at a small mineral water works in the Caledonian Road, Islington, in London in 1870. His Codd-neck bottle was designed to enclose a marble and a rubber washer in the neck. The bottles were filled upside down, and pressure of the gas in the bottle forced the marble against the washer, sealing in the carbonation. The bottle was pinched into a special shape to provide a chamber into which the marble was pushed to open the bottle. This prevented the marble from blocking the neck as the drink was poured.[5] R. White's, by now the biggest soft drinks company in London and south-east England, featured a wide range of drinks on their price list in 1887, all of which were sold in Codd's glass bottles, with choices including strawberry soda, raspberry soda, cherryade and cream soda.[17]

In 1892, the "Crown Cork Bottle Seal" was patented by William Painter, a Baltimore, Maryland machine shop operator. It was the first bottle top to successfully keep the bubbles in the bottle. In 1899, the first patent was issued for a glass-blowing machine for the automatic production of glass bottles. Earlier glass bottles had all been hand-blown. Four years later, the new bottle-blowing machine was in operation. It was first operated by Michael Owens, an employee of Libby Glass Company. Within a few years, glass bottle production increased from 1,400 bottles a day to about 58,000 bottles a day.

In America, soda fountains were initially more popular, and many Americans would frequent the soda fountain daily. Beginning in 1806, Yale University chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman sold soda waters in New Haven, Connecticut. He used a Nooth apparatus to produce his waters. Businessmen in Philadelphia and New York City also began selling soda water in the early 19th century. In the 1830s, John Matthews of New York City and John Lippincott of Philadelphia began manufacturing soda fountains. Both men were successful and built large factories for fabricating fountains. Due to problems in the U.S. glass industry, bottled drinks remained a small portion of the market throughout much of the 19th century. (However, they were known in England. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, published in 1848, the caddish Huntingdon, recovering from months of debauchery, wakes at noon and gulps a bottle of soda-water.[18])

In the early 20th century, sales of bottled soda increased greatly around the world, and in the second half of the 20th century, canned soft drinks became an important share of the market. During the 1920s, "Home-Paks" was invented. "Home-Paks"are the familiar six-pack cartons made from cardboard. Vending machines also began to appear in the 1920s. Since then, soft drink vending machines have become increasingly popular. Both hot and cold drinks are sold in these self-service machines throughout the world.

الانتاج

المنتجون

القيمة الغذائية

إن جميع المشروبات الغازية تعتبر ذات قيمة غذائية منخفضة، لا تحتوي على البروتينات أو الدهون أو الفيتامينات والمعادن، وإنما هي عبارة عن سائل يحوي كميات كبيرة من السكريات الخاوية (اي الخالية من القيمة الغذائية)، وكمية قليلة جداً من الأملاح. أما بالنسبة للمشروبات الغازية الخاصة بمرضى السكري والحمية الغذائية (الدايت)، فتركيبها مشابه للمشروبات الاعتيادية غير ان السكر استبدل بمركب الاسبرتام وهو عبارة عن حامضيين امينيين هما حام الاسبارتيك وحامض الفينيل، اللذان يولدان الطعم الحلو عند اتحادهما. وهذا المركب لا يصلح لفئة من الناس (الذين يعانون من مرض الفينيل كيتون يوريا).

التأثيرات الصحية

يرتبط استهلاك المشروبات الغازية المحلاة بالسكر بالسمنة،[19][20] سكري النمط الثاني، نخر الأسنان، وسوء التغذية.[20] وتميل الدراسات التجريبية إلى ارتباط المشروبات الغازية المحلاة بهذه الأمراض،[19][20] على الرغم من طعن باحثين آخرين في هذا الارتباط.[21][22] تحتوي "المشروبات المحلات" على شراب ذرة عالي الفركتوز، وتحتوى أنواع أخرى على سكروز.

السمنة وأمراض متعلقة بالوزن

تسوس الأسنان

نقص بوتاسيوم الدم

المشروبات الغازية وكثافة العظام

الحقائق الغذائية

محتوى السكر

البنزين

انظر أيضا

- Ade

- صودا مخفضة السعرات

- Fizz keeper

- قائمة المشروبات الغازية حسب البلد

- جعة غير كحولية

- Premix and postmix

المصادر

- ^ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations". United States Government. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) See §7.71, paragraphs (e) and (f). - ^ What Is Meant By Alcohol-Free? : The Alcohol-Free Shop

- ^ Bangor Daily News, April 8, 2010. http://www.bangordailynews.com/detail/126224.html

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 1135455961. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Colin Emmins. "SOFT DRINKS Their origins and history" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Soft Drink". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ Crandall, Philip; Chen, Chin Shu; Nagy, Steven; Perras, Georges; Buchel, Johannes A.; Riha, William (2000). "Beverages, nonalcoholic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_035. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (March 6, 2009). "The discovery of oxygen and Joseph Priestley". Thoughtco.com. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ أ ب "Priestley 1772: Impregnating water with fixed air" (PDF). truetex.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ أ ب "The great soda-water shake up". The Atlantic. October 2014. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Morgenthaler, Jeffrey (2014). Bar Book: Elements of cocktail technique. Chronicle Books. p. 54. ISBN 9781452130279. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ "Heritage: Meet Jacob Schweppe". Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Phosphates, in Smith, Andrew. The Oxford companion to American food and drink. Oxford University Press US, 2007, ISBN 0-19-530796-8, p.451

- ^ أ ب ت Emmins, Colin (1991). SOFT DRINKS – Their origins and history (PDF). Great Britain: Shire Publications Ltd. p. 8 and 11. ISBN 0-7478-0125-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Chester homeless charity teams up with lemonade brand". Cheshire Live. October 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Raustiala, Kal (August 28, 2013). "The Imperial Cocktail". Slate. The Slate Group. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ ""Secret lemonade drinker": the story of R White's and successors in Barking and Essex". Barking and District Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Brontë, Anne (1922). Wildfell Hall, ch. 30. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Malik, V.S.; Schulze, M.B.; Hu, F.B. (2006). "Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 84 (2): 274–28. PMID 16895873.

- ^ أ ب ت Vartanian, L.R.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. (2007). "Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). American Journal of Public Health. 97 (4): 667–675. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. PMC 1829363. PMID 17329656.

- ^ Gibson, Sigrid (2008). "Sugar-sweetened soft drinks and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence from observational studies and interventions". Nutrition Research Reviews. 21 (2): 134–147. doi:10.1017/S0954422408110976. PMID 19087367.

- ^ {{{author}}}, Soft drinks and weight gain: How strong is the link?, [[{{{publisher}}}]], [[{{{date}}}]].

وصلات خارجية

- State Laws & Regulations Governing Beverage Sales in Schools, American Beverage Association (PDF format)

- Pesticides in Coke, Centre for Science and Environment

- "Beverage group: Pull soda from primary schools", USAToday, August 17, 2005

- "After soda ban nutritionists say more can be done", Boston Globe, May 4, 2006

- "Critics Say Soda Policy for Schools Lacks Teeth New York Times, August 22, 2005

- "Soft Drinks in Schools", American Academy of Pediatrics,