لوڤيون

اللوڤي ( Luwians ؛ /ˈluːwiənz/) كانوا مجموعة من الشعوب الأناضولية عاشت في وسط وغرب وجنوب الأناضول، في ما هو اليوم تركيا، أثناء العصر البرونزي والعصر الحديدي. وكانوا يتكلمون اللغة اللوڤية، التي هي لغة هندو-أوروپية من الفرع الأناضولي، والتي كانت تُكتب بالمسمارية المستوردة من بلاد الرافدين، وكذلك بكتابة هيروغليفية، والتي كانت يستخدمها أحياناً أيضاً أقاربهم اللغويون الحوثيون.

ولعل كانت اللوڤية مستخدمة للحديث في منطقة جغرافية أكبر من اللغة الحيثية.[1]

التاريخ

الأصول

The origin of the Luwians can only be assumed. A wide variety of suggestions exist, even today, which are connected to the debate over the original homeland of the Indo-European speakers. Suggestions for the Indo-European homeland include present-day Armenia,[2] Iran,[2] the Balkans, the Pontic–Caspian steppe[3][4][5][6] and Central Asia.[citation needed] However, little can be proven about the route that led the ancestors of the Luwians to Anatolia. It is also unclear whether the separation of the Luwians from the Hittites and the Palaic speakers occurred in Anatolia or earlier.

It is possible that the Demircihüyük culture (c.3500–2500 BC) is connected with the arrival of Indo-Europeans in Anatolia, since Proto-Anatolian must have split off around 3000 BC at the latest on linguistic grounds.[7][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل]

العصر البرونزي الوسيط

Certain evidence of the Luwians begins around 2000 BC, with the presence of personal names and loan words in Old Assyrian Empire documents from the Assyrian colony of Kültepe, dating from between 1950 and 1700 BC (Middle Chronology), which shows that Luwian and Hittite were already two distinct languages at this point.

According to most scholars,[من؟] the Hittites were then settled in upper Kızılırmak and had their economic and political centre at Neša (Kaneš), from which the Hittite language gained its native name, nešili. The Luwians most likely lived in southern and western Anatolia, perhaps with a political centre at Purushanda. The Assyrian colonists and traders who were present in Anatolia at this time refer to the local people as nuwaʿum without any differentiation. This term seems to derive from the name of the Luwians, with the change from l/n resulting from the mediation of Hurrian.

الفترة الحيثية

The Old Hittite laws from the 17th century BC contain cases relating to the then independent regions of Palā and Luwiya. Traders and displaced people seem to have moved from one country to the other on the basis of agreements between Ḫattusa and Luwiya.[8] It has been argued that the Luwians never formed a single unified Luwian state, but populated a number of polities where they mixed with other population groups.[citation needed] However, a minority opinion holds that in the end they did form a unified force, and brought about the end of Bronze Age civilization by attacking the Hittites and then other areas as the Sea People.[citation needed]

During the Hittite period, the kingdoms of Šeḫa and Arzawa developed in the west, focused in the Maeander valley. In the south was the state of Kizzuwatna, which was inhabited by a mixture of Hurrians and Luwians. The kingdom of Tarḫuntašša developed during the Hittite New Kingdom, in southern Anatolia. The kingdom of Wilusa was located in northwest Anatolia on the site of Troy. Whether any of these kingdoms represented a Luwian state cannot be clearly determined based on current evidence and is a matter of controversy in contemporary scholarship.

According to the Oriental Institute, Luwian was spoken from the eastern Aegean coast to Melid and as far north as Alaca Hoyuk during the Hittite Kingdom.[1]

كيزواتنا

Kizzuwatna was the Hittite and Luwian name for ancient Cilicia. The area was conquered by the Hittites in the 16th century BC. Around 1500, the area broke off and became the kingdom of Kizzuwatna, whose ruler used the title of "Great King", like the Hittite ruler. The Hittite king Telipinu had to conclude a treaty with King Išputaḫšu, which was renewed by his successors. Under King Pilliya, Kizzuwatna became a vassal of the Mitanni. Around 1420, King Šunaššura of Mitanni renounced control of Kizzuwatna and concluded an alliance with the Hittite king Tudḫaliya I. Soon after this, the area seems to have been incorporated into the Hittite empire and remained so until its collapse around 1190 BC at the hands of Assyria and Phrygia.[citation needed]

شـِخا

شـِخا Šeḫa كانت منطقة ليديا القديمة. It is first attested in the fourteenth century BC, when the Hittite king Tudḫaliya I campaigned against Wilusa. After the conquest of Arzawa by Muršili II, Šeḫa was a vassal of the Hittite realm and suffered raids from the Arzawan prince Piyamaradu, who attacked the island of Lazpa which belonged to Šeḫa.[citation needed]

أرزاوا

Arzawa is already attested in the time of the Hittite Old Kingdom, but lay outside the Hittite realm at that time. The first hostile interaction occurred under King Tudḫaliya I or Tudḫaliya II. The invasion of the Hittite realm by the Kaskians led to the decline of Hittite power and the expansion of Arzawa, whose king Tarḫuntaradu was asked by Pharaoh Amenhotep III to send one of his daughters to him as a wife. After a long period of warfare, the Arzawan capital of Apaša (Ephesus) was surrendered by King Uḫḫaziti to the Hittites under King Muršili II. Arzawa was split into two vassal states: Mira and Ḫapalla.

فترة ما بعد الحيثيين

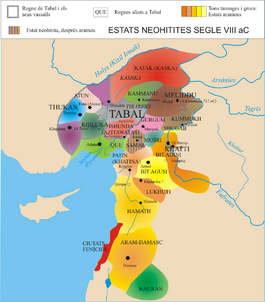

After the collapse of the Hittite Empire c. 1180 BCE, several small principalities developed in northern Syria and southwestern Anatolia. In south-central Anatolia was Tabal which probably consisted of several small city-states, in Cilicia there was Quwê, in northern Syria was Gurgum, on the Euphrates there were Melid, Kummuh, Carchemish and (east of the river) Masuwara, while on the Orontes River there were Unqi-Pattin and Hamath. The princes and traders of these kingdoms used Hieroglyphic Luwian in inscriptions, the latest of which date to the 8th century BC. The Karatepe Bilingual inscription of prince Azatiwada is particularly important.

These states were largely destroyed and incorporated into the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) during the 9th century BC.[9]

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ أ ب Goedegebuure, Petra (February 5, 2020). "Petra Goedegebuure Anatolians on the Move: From Kurgans to Kanesh". Oriental Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved January 5, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ أ ب Reich, David (2018), Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- ^ David W. Anthony (2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400831104.

- ^ Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei; Mittnik, Alissa; Bánffy, Eszter; Economou, Christos; Francken, Michael; Friederich, Susanne; Pena, Rafael Garrido; Hallgren, Fredrik; Khartanovich, Valery; Khokhlov, Aleksandr; Kunst, Michael; Kuznetsov, Pavel; Meller, Harald; Mochalov, Oleg; Moiseyev, Vayacheslav; Nicklisch, Nicole; Pichler, Sandra L.; Risch, Roberto; Guerra, Manuel A. Rojo; Roth, Christina; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Wahl, Joachim; Meyer, Matthias; Krause, Johannes; Brown, Dorcas; Anthony, David; Cooper, Alan; Alt, Kurt Werner; Reich, David (10 February 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe is a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". bioRxiv. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. bioRxiv 10.1101/013433. doi:10.1038/NATURE14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Allentoft, Morten E.; Sikora, Martin; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Rasmussen, Simon; Rasmussen, Morten; Stenderup, Jesper; Damgaard, Peter B.; Schroeder, Hannes; Ahlström, Torbjörn; Vinner, Lasse; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Margaryan, Ashot; Higham, Tom; Chivall, David; Lynnerup, Niels; Harvig, Lise; Baron, Justyna; Casa, Philippe Della; Dąbrowski, Paweł; Duffy, Paul R.; Ebel, Alexander V.; Epimakhov, Andrey; Frei, Karin; Furmanek, Mirosław; Gralak, Tomasz; Gromov, Andrey; Gronkiewicz, Stanisław; Grupe, Gisela; Hajdu, Tamás; Jarysz, Radosław (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- ^ Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Pickrell, Joseph; Meller, Harald; Guerra, Manuel A. Rojo; Krause, Johannes; Anthony, David; Brown, Dorcas; Fox, Carles Lalueza; Cooper, Alan; Alt, Kurt W.; Haak, Wolfgang; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (14 March 2015). "Eight thousand years of natural selection in Europe". bioRxiv: 016477. doi:10.1101/016477. Retrieved 3 April 2018 – via biorxiv.org.

- ^ H. Craig Melchert: The Luwians. Brill 2003, ISBN 90-04-13009-8, S. 23–26.

- ^ H. Craig Melchert: The Luwians. Brill 2003, ISBN 90-04-13009-8, pp. 28 f.

- ^ Georges Roux – العراق القديم

المصادر

- Hartmut Blum. “Luwier in der Ilias?”, Troia – Traum und Wirklichkeit: Ein Mythos in Geschichte und Rezeption, in: Tagungsband zum Symposion im Braunschweigischen Landesmuseum am 8. und 9. Juni 2001 im Rahmen der Ausstellung “Troia: Traum und Wirklichkeit”. Braunschweig: Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum, 2003. ISBN 3-927939-57-9, pp. 40–47.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2002). Life and Society in the Hittite World. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199241705.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2005) [1998]. The Kingdom of the Hittites (2nd revised ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199279081.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191505027.

- Bryce, Trevor R. (2016). "The Land of Hiyawa (Que) Revisited". Anatolian Studies. 66: 67–79. doi:10.1017/S0066154616000053. JSTOR 24878364. S2CID 163486778.

- Billie Jean Collins, Mary R. Bachvarova, & Ian C. Rutherford, eds. Anatolian Interfaces: Hittites, Greeks and their Neighbours. London: Oxbow Books, 2008.

- Gilibert, Alessandra (2011). Syro-Hittite Monumental Art and the Archaeology of Performance: The Stone Reliefs at Carchemish and Zincirli in the Earlier First Millennium BCE. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110222258.

- Hawkins, John David (1982). "The Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia". The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 372–441. ISBN 9780521224963.

- Hawkins, John David (1994). "The end of the Bronze age in Anatolia: New Light from Recent Discoveries". Anatolian Iron Ages. Vol. 3. London-Ankara: British Institute of Archeology at Ankara. pp. 91–94. ISBN 9781912090693.

- Hawkins, John David (1995a). "Karkamish and Karatepe: Neo-Hittite City-States in North Syria". Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 2. New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan. pp. 1295–1307. ISBN 9780684197210.

- Hawkins, John David (1995b). "Great Kings and Country Lords at Malatya and Karkamiš". Studio Historiae Ardens: Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul. pp. 75–86. ISBN 9789062580750.

- Hawkins, John David (1995c). "The Political Geography of North Syria and South-East Anatolia in the Neo-Assyrian Period". Neo-Assyrian Geography. Roma: Università di Roma. pp. 87–101.

- H. Craig Melchert, ed. The Luwians. Leiden: Brill, 2003, ISBN 90-04-13009-8.

- also in: Die Hethiter und ihr Reich. Exhibition catalog. Stuttgart: Theiss, 2002, ISBN 3-8062-1676-2.

- Melchert, Craig (2020). "Luwian". A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 239–256. ISBN 9781119193296.

- Osborne, James F. (2014). "Settlement Planning and Urban Symbology in Syro-Anatolian Cities". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 24 (2): 195–214. doi:10.1017/S0959774314000444. S2CID 162223877.

- Osborne, James F. (2017). "Exploring the Lower Settlements of Iron Age Capitals in Anatolia and Syria". Antiquity. 91 (355): 90–107. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.254. S2CID 164449885.

- Osborne, James F. (2020). The Syro-Anatolian City-States: An Iron Age Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199315833.

- Simon, Zsolt (2019). "Aramaean Borders: the Hieroglyphic Luwian Evidence". Aramaean Borders: Defining Aramaean Territories in the 10th–8th Centuries B.C.E. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 125–148. ISBN 9789004398535.

- Ilya S. Yakubovich. Sociolinguistics of the Luvian Language. Leiden: Brill, 2010. ISBN 978-90-04-17791-8.

- Eberhard Zangger. The Luwian Civilisation: The Missing Link in the Aegean Bronze Age. Istanbul: Yayinlari, 2016, ISBN 978-605-9680-11-0.

وصلات خارجية

- Luwian Studies.org

- Urs Willmann: Räuberbanden im Mittelmeer. In: Zeit Online, 2016

- "The Luwians: A Lost Civilization Comes Back to Life" keynote lecture by Dr. Eberhard Zangger given at Klosters' 50th Winterseminar, 18 January 2015 (online at Luwian Studies YouTube Channel)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from June 2022

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from December 2019

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Luwians

- شعوب قديمة في الشرق الأدنى

- شعوب أناضولية

- انهيار العصر البرونزي المتأخر

- شعوب هندو-اوروبية

- شعوب العصر البرونزي في آسيا

- شعوب العصر الحديدي في آسيا