كهوف بزقليك

| كهوف بزقليك | |

|---|---|

كهوف بزقليك | |

كهوف الألف بوذا في بزقليك (الصينية: 柏孜克里千佛洞; پنين: Bózīkèlǐ Qiānfódòng؛ إنگليزية: Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves) هي مجمع من مغارات وكهوف بوذية تعود إلى ما بين القرنين الخامس والرابع عشر بين مدينتي تورپان وشانشان (لولان) في شمال شرق صحراء تكلامكان بالقرب من الأطلال القديمة لـگاوچانگ في وادي موتو، الذي هو مضيق في الجبال الملتهبة، الصين. ويقعوا في أعلى الجروف بغرب وادي موتو تحت الجبال الملتهبة،[1] ومعظم الكهوف المتبقية تعود إلى مملكة قرةخوجة الأويغورية حوالي القرون العاشر إلى الثالث عشر.[2]

جداريات بزقليك

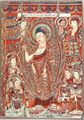

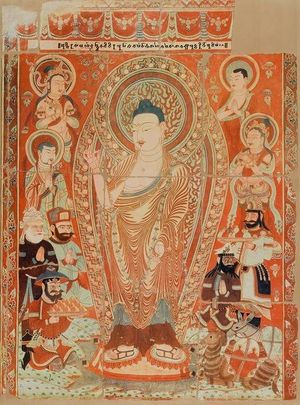

يوجد 77 كهف منحوتة في الموقع. معظمهم يحتوي على فراغات مستطيلة بأسقف مقوسة باستدارة وكثيراً ما تُقسـَّم إلى أربعة أقسام، كل منها به رسم جداري لبوذا. ونتج عن ذلك أن السقف بأكمله مغطى بمئات الرسوم الجدارية لبوذا. بعض الرسوم تُظهر بوذا كبير محاط بأشخاص آخرين، منهم الترك والهنود والاوروبيون. جودة الرسوم تتفاوت فبعضهم رسوماته ساذجة، بينما الآخرون هم قطع مبهرة من الفن الديني.[6] أفضل ما في كهوف الألف بوذا في بزقليكهم هم أولئك الجداريات الضخمة، اللائي أعطين الاسم "مشهد پرانيذي"، ويمثلون "وعد" أو "پرانيذي" ساكياموني من حياته السابقة.[7]

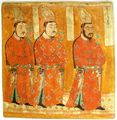

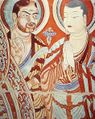

يصف الپروفسور جيمس ميلورد الأويغور الأصليين as physically Mongoloid, giving as an example the images in Bezeklik at temple 9 of the Uyghur patrons, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original Indo-European Tocharian inhabitants.[8] Buddhist Uyghurs created the Bezeklik murals.[9] However, Peter B. Golden writes that الأويغور not only adopted the writing system and religious faiths of the Indo-European Sogdians, such as Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Christianity, but also looked to the Sogdians as "mentors" while gradually replacing them in their roles as Silk Road traders and purveyors of culture.[10] Indeed, Sogdians wearing silk robes are seen in the praṇidhi scenes of Bezeklik murals, particularly Scene 6 from Temple 9 showing Sogdian donors to the Buddha.[4] The paintings of Bezeklik, while having a small amount of Indian influence, is primarily influenced by Chinese and Iranian styles, particularly Sasanian Persian landscape painting.[11] ألبرت فون لى كوك was the first to study the murals and published his findings in 1913. He noted how in Scene 14 from Temple 9 one of the Caucasian-looking figures with green eyes, wearing a green fur-trimmed coat and presenting a bowl with what he assumed were bags of gold dust, wore a hat that he found reminiscent of the headgear of Sasanian Persian princes.[12]

الأويغور البوذيون من قرةخواجة وتورفان were converted to Islam by conquest during a ghazat (holy war) على يد حاكم خانية چقطاي المسلم خضر خوجة (حكم 1389-1399).[13] After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously الأويغور البوذيون في تورفان failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[14]

الرسوم الجدارية في بزقليك have suffered considerable damage. Many of the temples were damaged by local Muslim population whose religion proscribed figurative images of sentient beings,; all statues were destroyed, some paintings defaced and others smeared with mud,[15] the eyes and mouths were often gouged out due to the local belief that the figures may otherwise come to life at night.[16] Michael Dillon considered Bezeklik's Thousand Buddha Caves are an example of the religiously motivated iconoclasm against depiction of religious and human figures.[17] Pieces of murals were also broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[15] During the late nineteen and early twentieth century, European and Japanese explorers found intact murals buried in sand, and many were removed and dispersed around the world. Some of the best preserved murals were removed by German explorer Albert von Le Coq and sent to Germany. Large pieces such as those showing Praṇidhi scene were permanently fixed to walls in the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin. أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية they could not be removed for safekeeping, and were thus destroyed when the museum was caught in the قصف برلين من قِبل الحلفاء.[15] وثمة قطع أخرى ربما تكون قد عُثر عليها في متاحف متعددة حول العالم، مثل متحف الإرميتاج في سانت پطرسبورگ، متحف طوكيو الوطني في اليابان، و المتحف البريطاني في لندن، والمتاحف الوطنية في كوريا و الهند.

ويوجد في اليابان نموذج رقمي لجداريات بزقليك التي أزالها المستكشفون.[2][18]

معرض صور

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "Bizaklik Thousand Buddha Caves". travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ أ ب Reconstruction of Bezeklik murals at Ryukoku Museum

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, p. 28, Tafel 20. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ أ ب Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134-163. ISSN 2191-6411. انظر أيضاً endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ^ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ "Bizaklik Thousand Buddha Caves". showcaves.com. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ The Lost Murals of Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0231139241. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Modern Chinese Religion I (2 vol.set): Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD). BRILL. 8 December 2014. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-90-04-27164-7.

- ^ Peter B. Golden (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 47, ISBN 978-0-19-515947-9.

- ^ Sims, Eleanor, Boris I. Marshak, Ernst J. Grube, (2002), Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 154, ISBN 0-300-09038-2.

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, p. 28. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ^ أ ب ت Whitfield, Susan (2010). "A place of safekeeping? The vicissitudes of the Bezeklik murals". In Agnew, Neville (ed.). Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road: proceedings of the second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China (PDF). Getty Publications. pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-30.

- ^ Hopkirk, Peter (2001). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0192802118.

- ^ Michael Dillon (1 August 2014). Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power: Kashgar in the Early Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-317-64721-8.

- ^ Ryukoku University Digital Archives Research Center

وصلات خارجية

- Chotscho: Facsimile Reproduction of Important Findings of the First Royal Prussian Expedition to Turfan in East Turkistan, Berlin, 1913. A catalogue of the findings of the Second German Turfan Expedition (1904–1905) led by Le Coq, containing colour reproductions of the murals. (National Institute of Informatics – Digital Silk Road Project Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books)

- Reconstruction of Bezeklik murals at Ryukoku Museum

- [ Bezeklik mural at Hermitage Museum]

- Silk Route photos

- Mogao Caves

- Silk Road site

- Articles using infobox templates with no data rows

- Pages using infobox cave with unknown parameters

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مواقع تاريخية وثقافية وطنية رئيسية في شينجيانگ

- مغارات بوذية صينية

- تورپان

- مواقع على طريق الحرير

- الدين في شينجيانگ

- كهوف شينجيانگ

- كهوف الصين

- التاريخ المعماري الصيني

- المعابد البوذية في تورفان