شلمنصر الثالث

| شـُلمانو-أشريدو Shalmaneser III | |

|---|---|

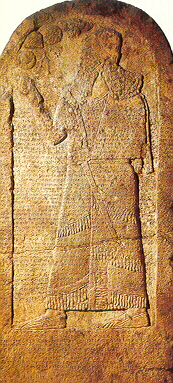

Shalmaneser III, on the Throne Dais of Shalmaneser III at the المتحف العراقي. | |

| ملك الامبراطورية الآشورية الحديثة | |

| العهد | 859–824 ق.م. |

| سبقه | آشور ناصر پال الثاني |

| Shamshi-Adad V | |

| وُلِد | 893-891 ق.م. |

| توفي | ح. 824 ق.م. |

| الأب | آشور ناصر پال الثاني |

| الأم | Mullissu-mukannishat-Ninua (?) |

شلمنصر الثالث Shalmaneser III (شـُلمانو-أشريدو، "الإله شلمانو هو السيد") كان ملك آشور في الفترة من 858-823 ق.م وهو ابن الملك آشور ناصر پال الثاني.

كانت فترة حكمه الطويل الذي دام خمسة وثلاثين عاما عبارة عن سلسة من الهجمات ضد القبائل الشرقية وقبائل بلاد الرافدين ، والبابليون وسوريا دون تفاصيلها على مسلة كبيرة من حجر أسود موجودة بالمتحف البريطاني.

وقد حارب شلمنصر سوريا وفلسطين وقضى على أحلاف الآراميين واليهود وحارب في الاناضول وهضبة إيران الشمالية وهاجم القبائل العربية في الصحراء وعمل على نشر الحضارة الاشورية في كل مكان.

وقد اتخذ شلمنصر مدينة كالح (النمرود) عاصمة له مثل أبيه إلا أنه بنى له قصراً قبالة مركز المدينة. وقدس الاله آشور وفضله على بقية الآلهة في بابل وبلاد الاشوريين.

عهده

الحملات

Shalmaneser began a campaign against the Urartian Kingdom and reported that in 858 BC he destroyed the city of Sugunia and then in 853 BC also Araškun. Both cities are assumed to have been capitals of the Kingdom before Tushpa became a center for the Urartians.[1] In 853 BC, a coalition was formed by 11 states, mainly by Hadadezer (Hadad-ezer) the Aramean king of Damascus, Irhuleni king of Hamath, Ahab king of Israel, Gindibu king of the Arabs, and some other rulers who fought the Assyrian king at the Battle of Qarqar. The result of the battle was not decisive, and Shalmaneser III had to fight his enemies several times again in the coming years, which eventually resulted in the occupation of the Levant (modern Syria and Lebanon) and Arabia by the Assyrian Empire.

In 851 BC, following a rebellion in Babylon, Shalmaneser led a campaign against Marduk-bēl-ušate, younger brother of the king, Marduk-zakir-shumi I, who was an ally of Shalmaneser.[2] In the second year of the campaign, Marduk-bēl-ušate was forced to retreat and was killed. A record of these events was made on the Black Obelisk:

In the eighth year of my reign, Marduk-bêl-usâte, the younger brother, revolted against Marduk-zâkir-šumi, king of Karduniaš, and they divided the land in its entirety. In order to avenge Marduk-zâkir-šumi, I marched out and captured Mê-Turnat. In the ninth year of my reign, I marched against Akkad a second time. I besieged Ganannate. As for Marduk-bêl-usâte, the terrifying splendor of Assur and Marduk overcame him and he went up into the mountains to save his life. I pursued him. I cut down with the sword Marduk-bêl-usâte and the rebel army officers who were with him.

— Shalmaneser III، Black Obelisk[i 1]

ضد إسرائيل

In 841 BC, Shalmaneser campaigned against Hadadezer's successor Hazael, forcing him to take refuge within the walls of his capital.[5] While Shalmaneser was unable to capture Damascus, he devastated its territory, and Jehu of Israel (whose ambassadors are represented on the Black Obelisk now in the British Museum), together with the Phoenician cities, prudently sent tribute to him in perhaps 841 BC.[6] Babylonia had already been conquered, including the areas occupied by migrant Chaldaean, Sutean and Aramean tribes, and the Babylonian king had been put to death.[7]

ضد تيبارني

In 836 BC, Shalmaneser sent an expedition against the Tibareni (Tabal) which was followed by one against Cappadocia, and in 832 BC came another campaign against Urartu.[8] In the following year, age required the king to hand over the command of his armies to the Tartan (turtānu commander-in-chief) Dayyan-Assur, and six years later, Nineveh and other cities revolted against him under his rebel son Assur-danin-pal. Civil war continued for two years; but the rebellion was at last crushed by Shamshi-Adad V, another son of Shalmaneser. Shalmaneser died soon afterwards.

الحملات اللاحقة

Despite the rebellion later in his reign, Shalmanesar had proven capable of expanding the frontiers of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, stabilising its hold over the Khabur and mountainous frontier region of the Zagros, contested with أورارتو.

وفي السنين الاخيرة من حكم شلمنصر ثار عليه أحد أبنائه وهو آشور دانن بال وسبب فتنا داخلية واضطرابات أدت إلى ضياع كثير من المستعمرات البعيدة وأنهى أخيه شمشي عضد الخامس الثورة وسحقها بتغلبه على أخيه الثائر.

في الدراسات التوراتية

His reign is significant to Biblical studies because two of his monuments name rulers from Hebrew Bible.[9] The Black Obelisk names Jehu son of Omri (although Jehu was misidentified as a son of Omri).[9] The Kurkh Monolith names king Ahab, in reference to the معركة قرقر.

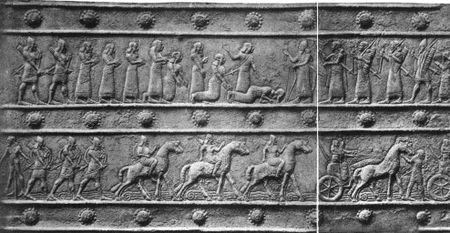

المسلة السوداء

He had built a palace at Kalhu (Biblical Calah, modern Nimrud), and left several editions of the royal annals recording his military campaigns, the last of which is engraved on the المسلة السوداء لشلمنصر الثالث من كالح.

The Black Obelisk is a significant artifact from his reign. It is a black limestone, bas-relief sculpture from Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), in northern Iraq. It is the most complete Assyrian obelisk yet discovered, and is historically significant because it displays the earliest ancient depiction of an Israelite. On the top and the bottom of the reliefs there is a long cuneiform inscription recording the annals of Shalmaneser III. It lists the military campaigns which the king and his commander-in-chief headed every year, until the thirty-first year of reign. Some features might suggest that the work had been commissioned by the commander-in-chief, Dayyan-Ashur.

The second register from the top includes the earliest surviving picture of an Israelite: the Biblical Jehu, king of Israel.[10] Jehu severed Israel's alliances with Phoenicia and Judah, and became subject to Assyria. It describes how Jehu brought or sent his tribute in or around 841 BC.[11][9] The caption above the scene, written in Assyrian cuneiform, can be translated:

"The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears."[9]

It was erected as a public monument in 825 BC at a time of civil war. It was discovered by archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1846.

جدول زمني

| سنة الحكم | السنة | أماكن حملاته.[12] |

|---|---|---|

| السنة 1 | 858 ق.م. | حبوشكيا (غرب بحيرة اورميا)، قرقميش، جبال أمانوس وسواحل للبحر المتوسط. |

| السنة 2 | 857 ق.م. | أهونو من بيت أديني, حتي (منابع الفرات ودجلة وحتى البحر المتوسط). |

| السنة 3 | 856 ق.م. | بيت أديني، نائري (u. a. Arzaškun), اورارتو وحبوشكيا. |

| السنة 4 | 855 ق.م. | أهونو من بيت أديني |

| السنة 5 | 854 ق.م. | Mazamua و Kaššiari-Gebirge. |

| السنة 6 | 853 ق.م. | آرام (معركة كركر / معركة ضد تحالف مضاد لآشور)[13], حتّي وحلب. |

| السنة 7 | 852 ق.م. | جزية من بلدان نائري |

| السنة 8 | 851 ق.م. | الملك البابلي مردوك-ذاكر-شومي bietet Bündnis an wg. innerer Unruhen (verursacht durch d. Bruder). |

| السنة 9 | 850 ق.م. | Erneute Unterstützung Babylons, Tributempfang der Chaldäer و Zug zum Persischen Golf. |

| السنة 10 | 849 ق.م. | قرقميش وآرام وHamath |

| السنة 11 | 848 ق.م. | تجدد الثورات في آرام وحماة (تحت قيادة حداد-عزر وإرحولني) |

| السنة 12 | 847 ق.م. | مدينة Paqarahubuna |

| السنة 13 | 846 ق.م. | Matiate im östlichen Kaššiari-Gebirge |

| السنة 14 | 845 ق.م. | Erneuter Aufstand von Aram und Hamath (Hadad-ezer und Irhuleni) |

| السنة 15 | 844 ق.م. | معاودة غزو بلاد Nairi |

| السنة 16 | 843 ق.م. | Mazamua, نمري، الملك مردوك-مدمق flüchtet. |

| السنة 17 | 842 ق.م. | Tribut von Hatti, Zedernfällen im Amanus-Gebirge |

| السنة 18 | 841 ق.م. | Erneuter Aufstand von einer von Aram angeführten Koalition. Letztmalige Erwähnung von Hadad-ezer. |

| السنة 19 | 840 ق.م. | Jagd im Hatti-Gebiet. Zedernfällen im Amanus-Gebirge. |

| السنة 20 | 839 ق.م. | „Musterung“ der Könige von Hatti („Aram-Koalition“)[14], Vorstoß bis Qu'e |

| السنة 21 | 838 ق.م. | Erneuter Aufstand von Aram. Erstmalige Erwähnung von Hasael. |

| السنة 22 | 837 ق.م. | Tabal (südlich von Kayseri) |

| السنة 23 | 836 ق.م. | Tributempfang von Tabal |

| السنة 24 | 835 ق.م. | Vorstoß nach Namri, in Parsua Empfang des Tributs von 27 Königen. Erstmalige Erwähnung der Meder. |

| السنة 25 | 834 ق.م. | Qu'e und Einnahme Festung Aramu von Bit-Agûsi (Land Jahan zwischen Karkemisch, Patin و حماة) |

| السنة 26 | 833 ق.م. | Qu'e, Tarsis und Zedernfällen im Amanus-Gebirge |

| السنة 27 | 832 ق.م. | Urartu und Zusammenstoß mit Seduru (Sarduri I.) |

| السنة 28 | 831 ق.م. | Niederschlagung Aufruhr in Patin |

| السنة 29 | 830 ق.م. | بدون سجل |

| السنة 30 | 829 ق.م. | Erneuter Kriegszug gegen Ḫubuškia, Mannäer und Parsua |

| السنة 31 | 828 ق.م. | Erneuter Kriegszug gegen Muṣaṣir, اورارتو ونمري |

| السنة 32 | 827 ق.م. | بدون سجل |

| السنة 33 | 826 ق.م. | بدون سجل |

| السنة 34 | 825 ق.م. | بدون سجل |

| السنة 35 | 824 ق.م. | بدون سجل |

معرض صور

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ Black Obelisk, BM WAA 118885, crafted c. 827 BC, lines 73–84

المصادر

- ^ Çiftçi, Ali (2017). The Socio-Economic Organisation of the Urartian Kingdom. Brill. p. 190. ISBN 9789004347588.

- ^ Jean Jacques Glassner, Mesopotamian Chronicles, Atlanta 2004,

- ^ Kuan, Jeffrey Kah-Jin (2016). Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions and Syria-Palestine: Israelite/Judean-Tyrian-Damascene Political and Commercial Relations in the Ninth-Eighth Centuries BCE (in الإنجليزية). Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-1-4982-8143-0.

- ^ Cohen, Ada; Kangas, Steven E. (2010). Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography (in الإنجليزية). UPNE. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-58465-817-7.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (6 March 2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. OUP Oxford. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-100293-9.

- ^ On the year that Jehu sent tribute, see David T. Lamb (22 November 2007). Righteous Jehu and His Evil Heirs: The Deuteronomist's Negative Perspective on Dynastic Succession. OUP Oxford. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-923147-8.

- ^ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ^ "In 836 Shalmaneser made an expedition against the Tibareni (Tabal) which was followed by one against Cappadocia" in Chisholm, Hugh; Garvin, James Louis (1926). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature & General Information (in الإنجليزية). Encyclopædia Britannica Company, Limited. p. 798.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cohen, Ada; Kangas, Steven E. (2010). Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography (in الإنجليزية). UPNE. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1-58465-817-7.

- ^ This is "the only portrayal we have in ancient Near Eastern art of an Israelite or Judaean monarch"in Cohen, Ada; Kangas, Steven E. (2010). Assyrian Reliefs from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II: A Cultural Biography (in الإنجليزية). UPNE. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-58465-817-7.

- ^ Kuan, Jeffrey Kah-Jin (2016). Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions and Syria-Palestine: Israelite/Judean-Tyrian-Damascene Political and Commercial Relations in the Ninth-Eighth Centuries BCE (in الإنجليزية). Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 64–66. ISBN 978-1-4982-8143-0.

- ^ siehe auch bei: Dietz Otto Edzard Geschichte Mesopotamiens, C.H. Beck Verlag München 2004, S. 196–198

- ^ Bericht auf dem schwarzen Obelisken der Koalition von Adad-idri (Hadad-ezer) von Aram, Irhuleni von Hamat und Ahab (A-ha-ab-bu) von Israel (KUR sir3-la-a-a) gegenüber. Die Identifikation von A-ha-ab-bu mit Ahab wird allerdings von einigen Forschern angezweifelt (Kelle 2002, 642). Die Schlacht von Qarqar endete ohne endgültigen Sieg für Salmanassar III.

- ^ König Jehu von Israel wird bezüglich Hasael erwähnt. In der Tel-Dan Inschrift berichtet Hasael weiter von einer Auseinandersetzung mit Jehu (eine Belagerung von Jehu ist zwar genannt, doch gibt die Inschrift keine weiteren Einzelheiten, auf Grund fehlender Bruchstücke, bekannt). Da die Tributzahlung von Jehu an Salmanassar III. erfolgte, muss der Regierungsantritt von Jehu zwischen dem 18. und 21. Regierungsjahr (ca.841/840 v. Chr.] liegen.

وصلات خارجية

Media related to شلمنصر الثالث at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to شلمنصر الثالث at Wikimedia Commons- Gates of Shalmanser III and Assunasirpal. Bronze Reliefs from the Gates of Shalmaneser King of Assyria

- Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III Babylonian and Assyrian Literature.

- Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

| سبقه Ashurnasirpal II |

King of Assyria 859–824 BC |

تبعه Shamshi-Adad V |