رقصة الموت

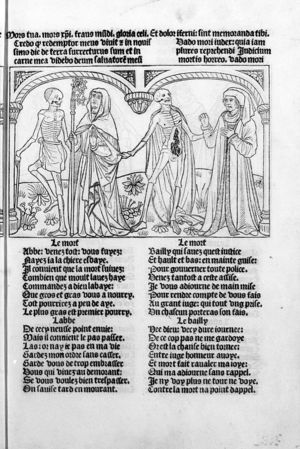

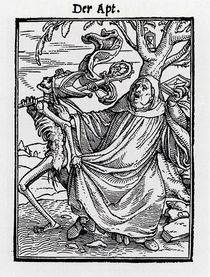

رقصة الموت Dance of Death، وأحياناً تسمى Danse Macabre (بالفرنسية)، Danza de la Muerte (بالإسپانية)، Danza Macabra (بالإيطالية)، Dança da Morte (بالبرتغالية)، Totentanz (بالألمانية)، Dodendans (بالهولندية)، Surmatants (بالإستونية)، Dansa de la Mort (بالقطلانية) هي صنف فني من الأمثولات القروسطية المتأخرة حول عمومية الموت: فبغض النظر عن مكانة الشخص في الحياة، فإن رقصة الموت توحـِّدنا جميعاً. وتتألف رقصة الموت من ميت أو تشخيص للموت يستدعي ممثلين من كل مناحي الحياة ليرقصوا معه إلى اللحد، وعادة ما يضموا پاپا، إمبراطور، ملك، طفل، وعامل. وكانت تلك الأعمال الفنية تُنتج لتـُذكـِّر الناس بقِصر الحياة وكيف هي زائلة مباهج الحياة الدنيا.[1] ويُفترض أن أصول ذلك الصنف الفني تعود إلى النصوص المصورة للخطب الكنسية؛ وأقدم نص مصور مسجل (مفقود الآن) هو جدارية في مقبرة القديسين البريئين في پاريس، تعود إلى 1424–1425.

اللوحات

Usually, a short dialogue is attached to each victim, in which Death is summoning him (or, more rarely, her) to dance and the summoned is moaning about impending death. In the first printed Totentanz textbook (Anon.: Vierzeiliger oberdeutscher Totentanz, Heidelberger Blockbuch, approx. 1460), Death addresses, for example, the emperor:

- Emperor, your sword won’t help you out

- Sceptre and crown are worthless here

- I’ve taken you by the hand

- For you must come to my dance

At the lower end of the Totentanz, Death calls, for example, the peasant to dance, who answers:

- I had to work very much and very hard

- The sweat was running down my skin

- I’d like to escape death nonetheless

- But here I won’t have any luck

The dance finishes (or sometimes starts) with a summary of the allegory's main point:

- Wer war der Thor, wer der Weise[r],

- "Who was the fool, who the wise [man],

- Wer der Bettler oder Kaiser?

- who the beggar or the Emperor?

- Ob arm, ob reich, im Tode gleich.

- Whether rich or poor, [all are] equal in death."

الطباعة

The earliest known depiction of a print shop appears in a printed image of the Dance of Death, in 1499, in Lyon, by Mattias Huss. It depicts a compositor at his station, which is raised to facilitate his work, and a person running the press. To the right of the print shop, an early book store is shown. Early print shops were gathering places for the literati.

تقاسيم موسيقية

تمثيلات في أوساط أخرى

Disney's animated Silly Symphonies short "The Skeleton Dance" (1929) makes extensive use of danse macabre imagery; the theme, as well as some of the animation from the film, would be recycled in a Mickey Mouse short, "The Haunted House," released the same year.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "Dance of Death". الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. 2007.02.20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

المراجع

- Israil Bercovici (1998) O sută de ani de teatru evriesc în România ("One hundred years of Yiddish/Jewish theater in Romania"), 2nd Romanian-language edition, revised and augmented by Constantin Măciucă. Editura Integral (an imprint of Editurile Universala), Bucharest. ISBN 973-98272-2-5.

- James M. Clark (1950) The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

- André Corvisier (1998) Les danses macabres, Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-049495-1.

- Rolf Paul Dreier (2010) Der Totentanz - ein Motiv der kirchlichen Kunst als Projektionsfläche für profane Botschaften (1425-1650), Leiden, ISBN 978-90-902511-1-0 with CD-ROM: Verzeichnis der Totentänze

- Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knoell (2011), Mixed Metaphors. The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-2900-7.

- Ann Tukey Harrison (1994), with a chapter by Sandra L. Hindman, The Danse Macabre of Women: Ms.fr. 995 of the Bibliothèque Nationale, Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-473-3.

- Romania, National Library of ... - Illustrated Latin translation of the Danse macabre, late 15th century. treasure 4

للاستزادة

- Hans Georg Wehrens: Der Totentanz im alemannischen Sprachraum. "Muos ich doch dran - und weis nit wan". Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7954-2563-0.

- Elina Gertsman (2010), The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages. Image, Text, Performance. Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages, 3. Turnhout, Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-53063-5

- [1] Sophie Oosterwijk (2004), 'Of corpses, constables and kings: the Danse Macabre in late-medieval and renaissance culture', The Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 157, 61-90.

- [2] Sophie Oosterwijk (2006), '"Muoz ich tanzen und kan nit gân?" Death and the infant in the medieval Danse Macabre', Word & Image, 22:2, 146-64.

- Sophie Oosterwijk (2008), 'Of dead kings, dukes and constables. The historical context of the Danse Macabre in late-medieval Paris', Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 161, 131-62.

- [3] Sophie Oosterwijk (2008), '"For no man mai fro dethes stroke fle". Death and Danse Macabre iconography in memorial art', Church Monuments, 23, 62-87, 166-68

- [4] Sophie Oosterwijk and Stefanie Knoell (2011), Mixed Metaphors. The Danse Macabre in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-2900-7.

- Marek Żukow-Karczewski, Taniec śmierci (Dance macabre), "Życie Literackie" ("Literary Life" - literary review magazine), 43/1989.

وصلات خارجية

- A collection of historical images of the Danse Macabre at Cornell's The Fantastic in Art and Fiction

- Holbein's Totentanz

- [5] Sophie Oosterwijk (2009), '"Fro Paris to Inglond"? The danse macabre in text and image in late-medieval England', Doctoral thesis Leiden University available online.

- Images of Danse Macabre (2001) Conceptual performance by Antonia Svobodová and Mirek Vodrážka in Čajovna Pod Stromem Čajovým in Prague 22 May 2001'.