تجريدة هاري نيل على الجزائر 1824

CONSULATE OF HUGH MCDONELL CONTINUED—EXPEDITION OF SIR

HARRY NEALE.

1823—1824.

Towarps the end of October 1823 news was received at Algiers that the Kabyles, who inhabit the mountainous district around Bougia, had revolted against the Government of that place ; several persons were killed on both sides, and a Turkish Mufti was taken prisoner and carried off as a hostage.’ These Kabyles furnished nearly all the free labourers obtainable at Algiers, and they were especially prized by the con- suls’ families as servants, on account of their fidelity. The Dey sent a message to all the consuls, through their respective dragomans, requiring them to sur- render any members of these tribes who might be in their service, in order that they shonld be treated as rebels, or hostages for the good behaviour of their brethren.

Mr. McDonell had a number of them in his ser- vice, and he immediately answered with becoming dignity that he would never consent to deliver them

up, alleging as reasons for his refusal the laws of nations and even the customs of the country, where the rights of hospitality were esteemed sacred. The Consul of the United States sent a similar reply, and informed the Khasnadji that he was unable to repulse force by force, and would make no effort to resist the arms of public authority ; yet to obtain the men in question it would be necessary to seize them in, and drag them from, the most inviolable part of his own residence. The French Consul, after an interview with the Minister of Marine, returned to his house, called all his Kabyles together, paid them their wages and dismissed them from his service, in presence of the dragoman and guardian, thus abandoning them to their enemies and renouncing the right of defending them in the name of the Government which he represented. The Consul of Holland on hearing what had passed assembled his Kabyles and gave them their choice of either re- maining under his protection or seeking safety in flight ; they elected the latter course, and so his house was respected.

Late in the evening of October 25 an armed troop procecded to the English garden and demanded the surrender of the Kabyles. Mr. McDonell at once put the official seals on his doors and hoisted above them the British flag. Nevertheless later in the day, by an express order from the Pasha, the seals were broken, the doors were forced, and the house every- where searched in the most scandalous manner, with- out even sparing the apartments of his wife and daughters, which should have been considered a

sacred asylum; this was the greatest insult which could have been offered in a Mohammedan country.

On October 27 the English Consul proposed that a protest against these arbitrary acts should be made by the European consuls, but it was not until early in December that this document was drawn out and presented by the consuls in a body to the Minister of Marine and Foreign Affairs, who promised to com- municate it to the Pasha.

The French Consul, a few days later, sent a de- spatch to Mr. McDonell, stating that his Government viewed with the greatest indignation the conduct of the Regency, that it regarded the European con- sulates at Algiers as inviolable, and it directed him to take, in concert with the English Consul, such measures as the latter might deem proper in the conjuncture, even though they should result in war.

On January 9, 1824, an English vessel arrived from Smyrna, bringing sixty recruits for the corps of Janissaries. Immediately on its arrival several Algerines went on board, and, without any apparent reason, grossly insulted the English captain. A few days later an Algerine cruiser brought in a prize taken under the Spanish flag. The officers and crew were immediately reduced to slavery, in defiance of the Treaty of 1816; this event excited unbounded joy among the population, who saluted it as a pre- sage of renewed prosperity for Algicrs. The English Consul protested against the treatment inflicted on the crew ; the Pasha replied curtly to his message, that the treaty in question had only been concluded for three years, and that Christian slavery should now recommence in Algiers.

On January 28 the British frigate Natad, com- manded by Captain the Hon. R. C. Spencer, arrived from the Tagus, with despatches to the consul rela- tive to the events of the previous October. His con- duct was entirely approved, and additional articles were forwarded by the British Government for the Dey’s signature, establishing more clearly the rights which that affair had called in question. The Dey hesitated to sign them, pretending that he did not. believe in their authority. Even if the affair of the Kabyles could have been amicably arranged, that of renewing slavery was a much more serious matter, and the consul deemed it his duty to embark his family on board the Naiad, and that all future negotia- tions should be conducted by Captain Spencer. Mr. McDonell recommended his houses, servants and effects to the care of the American Consul-General, and as Mrs. McDonell had embarked at a moment's notice, without even the most indispensable articles of apparel, Mr. Shaler’s first duty was to cause that lady’s effects to be packed up and to demand permis- sion to have them sent on board.

On January 31 the Pasha sent a message to Cap- tain Spencer by the Port Admiral, Hadji-Ali-Rais, who . was known for his intelligence and liberal views, ex- pressly renouncing the pretensions of reducing the Spanish prisoners to slavery, and promising that they should be treated assimple prisoners of war. He agreed to sign the articles proposed, and did not seem to make any great objection to what he considered the most inadmissible of them, the right of the consul to hoist the British flag at his town residence. These matters had been discussed at a Divan; the Dey obstinately maintained that no concession should be made, but he was obliged to defer to the opinion of all the other members, which was contrary to his. In the mean time Captain Spencer had landed and had embarked a large quantity of baggage which the consul had caused to be prepared. Subsequently the Pasha -withdrew his concession in the matter of the flag, and declared his intention of writing to the King of England, stating that he preferred war to dishonour. Captain Spencer replied that he had no discretionary power—the Pasha must sign unconditionally the articles submitted to him, or he must leave Algiers. The Dey asked if his departure was to be considered as tantamount to a declaration of war. Captain Spencer replied that he had no communication to make on this subject. Mr. McDonell again recom- mended to the American Consul all that he had been obliged to leave behind him, and he confided the consulates of Naples, Portugal, Austria and Tuscany, which were under his administration, to an employé who had been long in his service, M. Louis Granet. On the same day the Naiad and the brig Cameleon, which had arrived that very morning, weighed anchor.

As soon as the vessels had sailed, Mr. Shaler went to the Minister of Marine and Foreign Affairs, ac- companied by his dragoman and M. Granet as inter-preter, and informed him that as he was well aware of the bonds of friendship which united him to the English Consul, he would not be surprised to learn that all the effects which belonged to the latter had been committed to his care; that in consequence it was his intention to hoist the American flag at the English garden and generally to take under his pro- tection all that Mr. McDonell had left. The minister made no objection and gave the necessary orders.

Mr. Shaler narrates! that on the same day that he took possession of the English garden (January 31, 1824), a small Algerine cruiser was observed in the offing, chased by the English vessels, which kept up an uninterrupted fire.upon her. The former supported it with extraordinary courage for about an hour, till darkness hid them from view; for three-quarters of an hour the English vessels had fired upon it from half pistol range without being able to force it to surrender. On the following morning it appeared at anchor in the bay, dismasted, and making signals of distress ; it was towed in during the day, when it was ascertained that four men had been killed and eight wounded. The captain and his Spanish prisoners had been taken out of her.

The following is an account of the action taken from the log of H.M.S. Naiad?:—

At 3.30 P.M. observed a strange sail standing in for the land ; hoisted our colours and fired a shotted gun to make the

stranger show his; saw they were Algerine. Tacked ship in chase; signalled Cameleon to chase E.N.E.; made all sail and opened our larboard broadside on the chase, who made all sail away. At 4 p.m, the chase bore E.S.E. one mile and a half, running right in for the Bay of Algiers; we being between him and the town he could not steer for it. We kept up a constant fire of round shot till five, when we neared her and commenced firing grape and canister, which he returned with a few guns and small arms—the Cameleon also firing into him. At six, all the sails, rigging, fore and main yards, jibboom and other spars, being shot away on board the enemy, and being close off the shoals, tacked ship, leaving him unmanageable with only about five hands on deck. At 6.10, hove to and observed the Cameleon board the corvette ; wore ship and hailed him to let go the prize’s anchor, he informed me that he had possession of him ; shortened sail and anchored in eighteen fathoms water; sent boats and found the prize to be the Tripoli, eighteen 24-pounder carronades and eighty men, Rais Ca- doudje, coming in from a cruise and bound for Algiers, having on board seventeen Spanish ‘slaves, whom, with ber captain, we took out of her, she being too much shattered and cut up to bring out; cut away the anchor, but from the lumbered state of the cable it did not bring her up, and we left her drifting in close upon the town with the wind and swell both right on. At eight boats returned, found foretopgallant yards, maintopgallant mast, several sails and some rope shot away by the enemy’s fire.

The captain was sent back to Algiers on the con- clusion of peace.

Admiral Lord Clarence Paget, who was present at the action as a midshipman, informed the writer that the captain of the prize behaved in a manner that elicited universal admiration, and, indeed, the honours of war on this occasion seem to be due rather to the conquered than to the conquerors. No formal decla- ration of war had been made, and the Dey subse- quently remarked that had he been aware of Captain Spencer’s intentions, he would certainly have arrested both him and the consul. He actually sent orders to imprison the English Vice-Consul at Oran, but that gentleman happening also to be American agent, on a representation from Mr. Shaler he was immediately released.

On February 11 a French squadron, consisting of four frigates and aschooner, arrived in the bay. The commandant landed and had an audience of the Dey, but he was not permitted to do so till he had taken off his sword. The same formality had been exacted from Captain Spencer ; this was a newly-revived preten- sion on the part of His Highness, as Mr. Shaler had frequently introduced American officers, who always wore their swords. The object of the mission was to take advantage of the relations between the Regency and England, and to press for the solution of a ques- tion relative to the possession of a house and garden at Bona, then occupied by the English Vice-Consul, but which had been an object of litigation between Eng- land and France for seven years. The demand was complied with, and an order was sent that the French should be put in possession. The American Consul represented to the Regency that they would do well to consider the fact of their being at war with a great and powerful nation, and if it was not their intention to push this war-to extremity, sound policy demanded that they should abstain from any measures likely to produce irritation, or which might render the rupture more serious; that this right of possession accorded under existing circumstances to the French Consul at Bona would probably be regarded by the British Government as a fresh injury; that the conduct of the French Consul under existing circumstances was not remarkable for generosity, and would most probably be blamed by his own Government; he therefore recommended that if peace were desired, this cession should be suspended, and that no steps should be taken likely to complicate matters. The Pasha admitted that he had been too hasty, thanked the American Consul for his counsel, and begged him to inform the British Government that he was ready to do anything in his power likely to conduce to- wards the restoration of peace.

At a subsequent interview with His Highness and the Divan, Mr. Shaler repeated what he had said, and insisted strongly on the necessity of liberating the Spanish prisoners, as he felt sure that the question of renewing Christian slavery at Algiers was the one which would prove the most difficult to arrange ; that as regarded hoisting the British flag in the city, he thought this point might be waived if it were ex- plained that such a right was contrary to the religious prejudices of the people. They listened to these propositions with the greatest attention, and with the air of men who were of the same opinion, excepting in the matter of sending back the Spanish prisoners, to which they showed the greatest repugnance, and they finished by requesting the consul to send a letter from them to the British Government.

On February 22, H.MS. Regent, bearing the flag of Vice-Admiral Sir Harry B. Neale, accompanied by the Naiad, arrived in the bay. At the earnest solicitation of the Dey, Mr. Shaler proceeded on board to ask the Admiral what were his intentions; the latter replied that Great Britain considered itself at war with the Regency, but that he had no particular instructions, except to maintain a rigorous blockade, and to adopt every measure of hostility that he might think advisable, until the Dey consented to sign the declaration that had been submitted to him by His Majesty’s Government. On the following day the Pasha sent off a message stating that he was ready to submit to all the British demands except the right of hoisting the flag in town, and he repeated what he had stated in his letter to Lord Bathurst, that the Regency was ready to expose itself to the worst chances of a war rather than consent to such an article.

On the receipt of this message Sir Harry Neale weighed anchor. Mr. Shaler, seeing that the majority of the Algerine Cabinet was desirous of peace, was determined to use all his efforts to promote it. He pointed out the danger of their position; that it was ridiculous for Algiers to contend against England, and that if once the questions in dispute, now so easy to settle, should become national ones, the war would necessarily terminate in the ruin of Algiers. The Agha of Janissaries thoroughly understood the state of the case, and begged Mr. Shaler to make some excuse to get an interview with the Pasha, as neither he nor any other Algerine dared represent the true state of the case to him. The Dey received him with much politeness, but replied by arguments drawn from the most absurd notions of fatalism, and by the most ridiculous presumption. He added that, in spite of his desire to conclude an honourable peace, he would never consent to the return of Mr. McDonell as representative ‘of his nation at Algiers. Mr. Shaler remarks: It'is interesting to record that this consul has ‘several very young children; that his dominating passions are gardening and agriculture, and that no one could charge him with the slightest abuse of power.’ This conveys a very inadequate idea of Mr. McDonell’s character. For many years he had rendered excellent service to the State. The Duke of Kent had always entertained the highest opinion of his character and abilities, and main- tained a constant personal correspondence with him. A letter written by Lieutenant-Colonel Harvey con- tains a most flattering testimony to his worth: ‘ His Royal Highness has always understood, from those who have had occasion to be acquainted with his pro- ceedings at Algiers, that his conduct has invariably met with the highest approbation of Government for the judgment and firmness he has evinced in the most trying moments, a circumstance peculiarly gratify- ing to the Duke, who reflects with pleasure upon his being the first who brought him forward.’

For the next few days the number of vessels of the squadron varied considerably. On March 7 it consisted of the flagship and six frigates, and still maintained a rigorous blockade. Mr. Shaler learnt that the vice-consul and several British subjects at Bona had been put in prison and treated with exces- sive rigour. He remonstrated against this useless severity, and received from the Dey an assurance that they would be at once set at liberty, and treated with all the indulgence possible towards prisoners of war. During the month of March several messages were sent by the Admiral under flag of truce. The Pasha was so irritated at finding himself alone in the council, in the question of the dispute between Algiers and Great Britain, that he affected to believe that the Admiral was not authorised to treat defini- tively with him on the subject of peace or war, and that the result was a reciprocal misunderstanding. Sir Harry Neale sent one of his captains on shore to represent him, but he was kept waiting for three hours, after which time the Pasha refused to receive him at all, declaring that he would only treat with the Admiral in person.

Sir Harry Neale, carrying forbearance to its ut- most limit, landed on March 28, and had an interview with the Dey ; the latter agreed to all the articles of peace, excepting to the return of Mr. McDonell, whom he positively refused to receive. On the 29th the Admiral weighed anchor and left the bay. On the day following the interview, the Pasha ordered Mr. Bensamon, his Jewish interpreter, to write to the Admiral on the back of one of his own letters to this effect : That he had not declared war upon England, and that he did not believe that he had given that nation any excuse for declaring it on him; that he desired peace, and would accept the conditions pro- posed by the Admiral, but that nothing would induce him to receive back Mr. McDonell; that he had just received, by express, the news of an attack made on the town of Bona by two English frigates ; that a neutral vessel had been captured, much damage caused, and several of his subjects killed and wounded ; this conduct did not appear to him in accordance with the language of the Admiral at the previous day’s conference. This letter was written in bad English, signed by the Pasha, and, in accordance with his express instructions, wrapped up in a bit of dirty paper, and so sent tothe Admiral. Well might Mr. Shaler remark: ‘When one sees the insolent pride of these barbarians, their ignorance of the forms usual in diplomatic relations, and the too great for- bearance which the English Admiral has shown in these negotiations, one can hardly venture to hope for an honourable result to the war between Algiers and Great Britain.’

The incident at Bona is thus alluded to by Lord Clarence Paget : ! ‘ During the spring of 1824 we were continually blockading the coast between Algiers and Bona. At the latter place we sent the boats in at night and burnt a brig of war under the batteries, for which feat the officer in command was promoted.’

On July 11, Sir Harry Neale, with his flag on

1 Ina private letter to the Author,

board H.M.S. Revenge, anchored in the bay, about three miles from the sea batteries. Three frigates anchored successively to the south. On the following day several other vessels joined the squadron, and a small brig was detached to anchor in front of the entrance of the port. In the evening the Algerines sent out their flotilla to manceuvre as usual. Think- ing that the brig was within range, they fired on her, and then commenced a general cannonade between the squadron, the flotilla, and the batteries, which lasted an hour; it was supposed that the Admiral provoked this fire to learn the range of the Algerine batteries.

On July 24 the British squadron, consisting of twenty-two vessels including a steamer, anchored before the town. The flotilla commenced to open fire, and a brisk cannonade ensued, which was only stopped by a signal from the Kasbah.

Lord Clarence Paget says of this action: ‘It was altogether a sorry affair, and the only thing interesting about it was the appearance, for the first time in action, of a war steamer, which had her funnel shot away. The strange thing was that out of this little Mole there came daily hundreds of fine galleys fully armed, and no one could understand how they could find room for them, besides several large frigates and corvettes inside.’

The Admiral consented to re-open negotiations, at the same time disposing his squadron for a more effi- cient attack if necessary, in a curved line, facing the town, about a mile in extent. The Pasha sent to inform the Admiral that he would accede to all the British demands except the return of the consul. He said he had no personal objection to him, but that he had become so odious to the people that he was sure if he landed he would not be able to protect him against their fury. This was altogether a false pretext, but the Pasha had it in his power to give it the colour of truth, by instigating a tumultuous mob to receive Mr. McDonell on debarking. Instead of holding the Algerine Government responsible, a matter which would have been very simple with such impos- ing forces at command, the Admiral, through motives of humanity, refused to allow him to be exposed to so great danger, and consented that a pro-consul should take charge of the consulate. Thus the expedition proved like the fable of the mountain in labour, and Hussein Pasha, by obstinately following a line of politics contrary to the opinion of all his council, raised himself to a degree of moral power and con- sideration such as few Deys in modern times had attained. Mr. Shaler visited the Admiral on board the Revenge; the latter begged him in case of necessity to assist the pro-consul with his advice ; he also met his friend Mr. McDonell, the victim of these strange negotiations. Mr. Shaler landed in company with the pro-consul, Mr. Danford, and took him to the American Consulate till his own house could be got ready.

Before leaving Algiers, the Admiral, accompanied by Captains Spencer, Bliffond, Burrard, and several other officers, went on shore, visited Mr Shaler, bade farewell to the Dey, and after a collation at the American Consulate, returned on board, leaving the Naiad still in the bay. Mr. Shaler demanded an audience from the Minister of Marine, to whom he spoke about M. Granet, the English Vice-Consul, whom the Government would not permit, even at the request of the British authorities, to reside any longer at Algiers, although he was the only person able to arrange the pecuniary affairs of Mr. McDonell. With great difficulty he succeeded in obtaining per- mission for him to remain for a short period. The Naiad left on August 11, Captain Spencer having first addressed a very cordial letter of thanks to Mr. Shaler for the great assistance he had rendered to himself and to the squadron generally. Mr. McDonell himself in a letter to his wife says of this good and faithful friend : ‘ Poor Shaler is over- whelmed ; his conduct has been beyond all praise.’

The substance of the declarations made by the Dey have already been given; they may be found in extenso in Hertslet’s ‘ Treaties,’ vol. iii. p. 14; another declaration, not published, regarding hoisting the flag on the consulate in town, which point was also waived, is as follows :—

His Highness the Dey of Algiers, in proof of his sincere disposition to respect and maintain inviolably for the future the rights and privileges that are attached to the person and residences of His Britannic Majesty’s consul, consents to sign the declaration that has been presented to him; but the Dey, having represented the nature of his repugnance against, that part of the declaration which stipulates that His Majesty’s flag shall be hoisted on the town house of the British Consul, requests that His Majesty the King of Great Britain and Ireland will not require a strict compliance with that part of the declaration.

The Dey, however, assures His Majesty, in the strongest and most explicit terms, that it is not intended by His Highness that the absence of the flag over the consul’s house, within the town of Algiers, shall be considered as depriving that house in any degree of any right or privilege which may attach to the hoisting of that flag over the consul’s house in the country.

Mr. McDonell was as badly treated as many of his predecessors had been; he was pensioned off in the prime of life, and the Government declined to support a heavy claim he had on the Portuguese Government for money advanced by him to the Dey on account of that power. Perhaps he was too out- spoken, and not very judicious in the manner in which he had commented on British policy. Such offences were not readily pardoned at the beginning of this century.

It is gratifying to be able to chronicle one good result arising from the failure of this expedition ; it gave the Dey an exaggerated idea of his own import- ance, it inflamed his pride, and, happily for humanity, it hastened his fall.

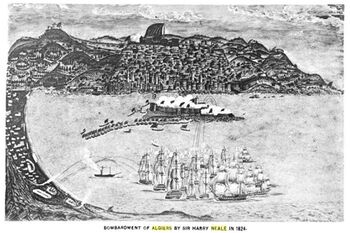

He was so satisfied with what he very naturally considered his victory over the British squadron, that he commissioned a native artist to make a painting of the bombardment; this was found in his palace on the French occupation, and a copy is preserved in the Library at Algiers and forms the subject of Plate VI. [4] The author hopes he may be pardoned for lifting a corner of the veil which ought to shroud the events of private life. Mr. McDonell married his second wife at Algiers in 1815. She was the daughter of Admiral Ulrich, Danish Consul-General, who had been treated by the Dey even worse than his English colleague. The dramatic escape of herself and her infant before the battle of Algiers is narrated in Lord Exmouth’s despatch. After Mr. McDonell’s death she married the Duc de Talleyrand-Perigord, and died at Florence on October 2, 1880, in her eightieth year.

Very shortly before her death she wrote to the author a long and interesting letter, of which the fol- - lowing is an extract :—

In 1804 my father, Admiral Ulrich, was appointed consul- general to Algiers (probably to replace Mr. de Bille). He proceeded to Algiers with my mother and five children. ‘My eldest sister married at Algiers Mr. Carstensen, whose daughter is married to Sir John Drummond Hay, British Minister at Morocco. In 1811 Mr. McDonell, under the patronage of H.R.H. the Duke of Kent, was sent to Algiers as consul-general, and we were married in the beginning of 1815. He was a widower and had four daughters, who all married : one to CaptainBuch,R.N. ; another to Mr. Holstein, who succeeded my father; a third to General Sir George Brown, who held a command in the Crimea ; and the fourth to Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Wynyard, military governor at the Cape of Good Hope ; all dead.

We had seven children; the eldest, who made herself so conspicuous at the time of the bombardment, died at an early age.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Tam principally indebted to the journals and official correspond- ence of Mr. William Shaler for an account of the events terminating in Sir Harry Neale's expedition against Algiers.

- ^ Journal of the American Consulate.

- ^ Communicated to the author by the nephew of the commander, Earl Spencer, K.G.

- ^ See Description of Plate, p. xiii.