زهد

الزهد (إنگليزية: Asceticism، /əˈsɛtɪsɪzəm/; من باليونانية: ἄσκησις) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals.[3] Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their practices or continue to be part of their society, but typically adopt a frugal lifestyle, characterised by the renunciation of material possessions and physical pleasures, and also spend time fasting while concentrating on the practice of religion or reflection upon spiritual matters.[4] Various individuals have also attempted an ascetic lifestyle to free themselves from addictions, some of them particular to modern life, such as alcohol, tobacco, drugs, entertainment, sex, food, etc.[5][citation needed]

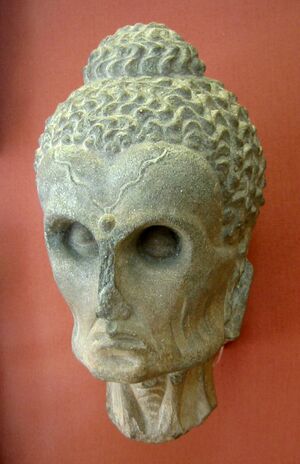

Asceticism has been historically observed in many religious traditions, including Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Judaism and Pythagoreanism and contemporary practices continue amongst some religious followers.[6]

The practitioners of this philosophy abandon sensual pleasures and lead an abstinent lifestyle, in the pursuit of redemption,[7] salvation or spirituality.[8] Many ascetics believe the action of purifying the body helps to purify the soul, and thus obtain a greater connection with the Divine or find inner peace. This may take the form of rituals, the renunciation of pleasure, or self-mortification. However, ascetics maintain that self-imposed constraints bring them greater freedom in various areas of their lives, such as increased clarity of thought and the ability to resist potentially destructive temptations. Asceticism is seen in the ancient theologies as a journey towards spiritual transformation, where the simple is sufficient, the bliss is within, the frugal is plenty.[4] Inversely, several ancient religious traditions, such as Zoroastrianism, Ancient Egyptian religion,[9] and the Dionysian Mysteries, as well as more modern Left Hand traditions, openly reject ascetic practices and either focus on various types of hedonism or on the importance of family life, both rejecting celibacy.

الديانات

الديانات الإبراهيمية

المسيحية

| جزء من سلسلة مقالات عن |

| التصوف المسيحي |

|---|

|

الإسلام

اليهودية

البهائية

الديانات الهندية

البوذية

الثراڤادا

الماهيانا

الهندوسية

الجاينية

ممارسة الرهبنة

السيخية

ديانات أخرى

الإنكا

الطاوية

الزرداشتية

الآراء الاجتماعية والنفسية

آراء نيتشه وإپيقور

انظر أيضاً

- زهد (تصنيف)

- Abstinence

- Aesthetism

- Altruism

- Anatta

- Anti-consumerism

- Arthur Schopenhauer

- Cenobite

- Ctistae

- Cynicism

- Decadence (usually opposite)

- Desert Fathers

- Desert Mothers

- Egoism

- Epicureanism

- Fasting

- Flagellant

- Gustave Flaubert

- Hedonism (opposite)

- Hermit

- Hermitage

- Lent

- Mellified man

- Minimalism

- Monasticism

- Nazirite

- Paradox of hedonism

- Ramadan

- Rechabites

- Sensory deprivation

- Simple living

- Siddha

- Stoicism

- Straight edge

- Temperance (virtue)

الهوامش

الحواشي

المصادر

- ^ Randall Collins (2000), The sociology of philosophies: a global theory of intellectual change, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674001879, page 204

- ^ William Cook (2008), Francis of Assisi: The Way of Poverty and Humility, Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1556357305, pages 46-47

- ^ "Asceticism". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ أ ب Richard Finn (2009). Asceticism in the Graeco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–97. ISBN 978-1-139-48066-6.

- ^ Deezia, Burabari S (Autumn 2017). "IAFOR Journal of Ethics, Religion & Philosophy" (PDF). Asceticism: A Match Towards the Absolute. 3 (2): 14. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Deezia, Burabari S (Autumn 2017). "IAFOR Journal of Ethics, Religion & Philosophy" (PDF). Asceticism: A Match Towards the Absolute. 3 (2): 14. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Vincent L. Wimbush; Richard Valantasis (2002). Asceticism. Oxford University Press. pp. 247, 351. ISBN 978-0-19-803451-3.

- ^ Lynn Denton (1992). Julia Leslie (ed.). Roles and Rituals for Hindu Women. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 212–219. ISBN 978-81-208-1036-5.

- ^ Wilson, John A. (1969). "Egyptian Secular Songs and Poems". Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 467.

المراجع

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015), Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-53853-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=nfOPCgAAQBAJ

- Cort, John E. (2001a), Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513234-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=PZk-4HOMzsoC

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 0-87779-044-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=ZP_f9icf2roC

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains (2nd ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X, https://books.google.com/books?id=X8iAAgAAQBAJ

- Fujinaga, S. (2003), Qvarnström, Olle, ed., Jainism and Early Buddhism: Essays in Honor of Padmanabh S. Jaini, Jain Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-89581-956-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=5_EdL2FtIqQC&pg=PA206

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra (1st ed.), Uttarakhand: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=zLmx9bvtglkC, "

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع."

هذا المقال يضم نصاً من هذا المصدر، الذي هو مشاع." - Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The A to Z of Jainism, 38, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=cIhCCwAAQBAJ

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprinted 1999), ISBN 81-208-1376-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=WzEzXDk0v6sC

- Winternitz, Moriz (1993), History of Indian Literature: Buddhist & Jain Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=Lgz1eMhu0JsC

قراءات إضافية

- Valantasis, Richard. The Making of the Self: Ancient and Modern Asceticism. James Clarke & Co (2008) ISBN 978-0-227-17281-0.

وصلات خارجية

- Asketikos- articles, research, and discourse on asceticism.