الحكم العسكري البرازيلي

United States of Brazil Estados Unidos do Brasil (1937–1967) Federative Republic of Brazil República Federativa do Brasil (1967–1985) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964–1985 | |||||||||

Motto: "Ordem e Progresso" "Order and Progress" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المكانة | Federal republic Constitutional republic Presidential system Dominant-party system | ||||||||

| العاصمة | Brasilia | ||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | Portuguese | ||||||||

| الحكومة | Federal two-party (de facto dominant-party) presidential republic (de facto autocracy) under military dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1964–1967 | Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco | ||||||||

• 1967–1969 | Artur da Costa e Silva | ||||||||

• 1969–1974 | Emílio Garrastazu Médici | ||||||||

• 1974–1979 | Ernesto Geisel | ||||||||

• 1979–1985 | João Figueiredo | ||||||||

| Junta | |||||||||

• 1969 | Aurélio de Lyra Tavares Augusto Hamann Rademaker Grünewald Márcio Melo | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Cold War | ||||||||

• تأسست | March 31 1964 | ||||||||

• انحلت | March 15 1985 | ||||||||

| Currency | Cruzeiro | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Brazilian military government was the authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from April 1, 1964 to March 15, 1985. It began with the 1964 coup d'état led by the Armed Forces against the administration of the President João Goulart, who had assumed the office after being vice-president, upon the resignation of the democratically elected president Janio Quadros, and ended when José Sarney took office on March 15, 1985 as President. The military revolt was fomented by Magalhães Pinto, Adhemar de Barros, and Carlos Lacerda (who had already participated in the conspiracy to depose Getulio Vargas in 1945), Governors of Minas Gerais, São Paulo, and Guanabara. The coup was also supported by the Embassy and State Department of the الولايات المتحدة.[1]

The military dictatorship lasted for almost twenty-one years; despite initial pledges to the contrary, military governments in 1967 enacted a new, restrictive Constitution, and stifled freedom of speech and political opposition with support from the U.S. government. The regime adopted nationalism, economic development, and Anti-Communism as its guidelines.

The dictatorship reached the height of its popularity in the 1970s, with the so-called Brazilian Miracle (helped by much propaganda), even as the regime censored all media, tortured and banished dissidents. In March 1979, João Figueiredo became President, and while combating the "hard-line" and supporting a re-democratization policy, he couldn't control the chronic inflation and concurrent fall of other military dictatorships in South America. Brazilian Presidential elections of 1984 were won by opposition civilian candidates. In 1979 Figueiredo passed the Amnesty Law for political crimes committed for and against the regime. Since the 1988 Constitution was passed and Brazil returned to full democracy, the military have remained under control of civilian politicians, with no role in domestic politics.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Brazil’s military regime provided a model for other military regimes and dictatorships around Latin America, systematizing the “Doctrine of National Security,”[2] which "justified" the military’s actions as operating in the interest of National Security in a time of crisis, creating an intellectual basis upon which other military regimes relied.[2]

الأسباب وراء الانقلاب

Brazil's political crisis stemmed from the way in which the political tensions had been controlled in the 1930s and 1940s during the Vargas Era. Vargas' dictatorship and the presidencies of his democratic successors marked different stages of Brazilian populism (1930–1964), an era of economic nationalism, state-guided modernization, and import substitution trade policies. Vargas' policies were intended to foster an autonomous capitalist development in Brazil, by linking industrialization to nationalism, a formula based on a strategy of reconciling the conflicting interests of the middle class, foreign capital, the working class, and the landed oligarchy.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Essentially, this was the epic of the rise and fall of Brazilian populism from 1930 to 1964: Brazil witnessed over the course of this time period the change from export-orientation of the First Brazilian Republic (1889–1930) to the import substitution of the populist era (1930–1964) and then to a moderate structuralism of 1964–80.[بحاجة لمصدر] Each of these structural changes forced a realignment in society and caused a period of political crisis. Period of right-wing military dictatorship marked the transition between populist era and the current period of democratization.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The Brazilian Armed Forces acquired great political clout after the Paraguayan War. The politicization of the Armed Forces was evidenced by the Proclamation of the Republic, which overthrew the Empire, or within Tenentismo (Lieutenants' movement) and the Revolution of 1930. Tensions escalated again in the 1950s, as important military circles (the "hard-line militars", old positivists whose origins could be traced back to the AIB and the Estado Novo) joined the elite, medium classes and right-wing activists in attempts to stop Presidents Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart from taking office, due to their supposed support for Communist ideology. While Kubitschek proved to be friendly to capitalist institutions, Goulart promised far-reaching reforms, expropriated business interests and promoted economical-political neutrality with the USA.

After Goulart suddenly assumed power in 1961, society became deeply polarized, with the elites fearing that Brazil would become another Cuba and join Communist Bloc, while many thought that the reforms would boost greatly the growth of Brazil and end its economical subservience with the USA, or even that Goulart could be used to increase the popularity of the Communist agenda. Influential politicians, such as Carlos Lacerda and even Kubitschek, media moguls (Roberto Marinho, Octávio Frias, Júlio de Mesquita Filho), the Church, landowners, businessmen, and the middle class[بحاجة لمصدر] called for a coup d'état by the Armed Forces to remove the government. The old "hard-line" army officers, seeing a chance to impose their positivist economic program, convinced the loyalists that Goulart was a communist menace.[بحاجة لمصدر]

گولارت وسقوط الجمهورية الثانية

After the Presidency of Juscelino Kubitschek, the right wing opposition elected Jânio Quadros, who based his electoral campaign on criticizing Kubitschek and government corruption. Quadros' campaign symbol was a broom, with which the president would "sweep away the corruption."[3] In his brief tenure as president, Quadros made moves to resume relations with some communist countries, made some controversial laws and law proposals, but without legislative support, he couldn't follow his agenda.[4]

تورط الولايات المتحدة

The USA Ambassador Lincoln Gordon later admitted that the embassy had given money to anti-Goulart candidates in the 1962 municipal elections, and had encouraged the plotters; many extra United States military and intelligence personnel were operating in four United States Navy oil tankers and the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal, in an operation code-named Operation Brother Sam. These ships had positioned off the coast of Rio de Janeiro in case Brazilian troops required military assistance during the 1964 coup. A document from Gordon in 1963 to US president John F. Kennedy also describes the ways João Goulart should be put down, and his fears of a communist intervention supported by the Soviets or by Cuba.,[6][7]

Washington immediately recognized the new government in 1964, and hailed the coup d'état as one of the "democratic forces" that had allegedly staved off the hand of international communism. American mass media outlets like Henry Luce's TIME also gave positive remarks about the dissolution of political parties and salary controls at the beginning of Castello Branco mandate.[8]

الانقسام في صفوف العسكر

تأسيس النظام، كاستلو برانكو

The Army could not find a civilian politician acceptable to all of the factions that supported the ouster of João Goulart. On April 9, 1964 coup leaders published the First Institutional Act, which greatly limited the freedoms of the 1946 constitution. President was granted authority to remove elected officials from office, dismiss civil servants, and revoke for 10 years the political rights of those found guilty of subversion or misuse of public funds.[9] On April 11, 1964 the Congress elected the Army Chief of Staff, Marshal Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco as President for the reminder of Goulart's term.

Castelo Branco had intentions of overseeing a radical reform of the political-economic system and then returning power to elected officials. He refused to remain in power beyond the remainder of Goulart's term or to institutionalize the military in power. However, competing demands radicalized the situation. Military "hard-line" wanted a complete purge of left-wing and populist influences while civilian politicians obstructed Castelo Branco's reforms. The latter accused him of hard-line actions to achieve his objectives, and the former accused him of leniency. On October 27, 1965, after victory of opposition candidates in two provincial elections, he signed the Second Institutional act which purged Congress, removed objectionable state governors and expanded President's arbitrary powers at the expense of the legislative and judiciary branches. This gave him the latitude to repress the populist left but also provided the subsequent governments of Artur da Costa e Silva (1967–69) and Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969–74) with a "legal" basis for their hard-line authoritarian rule.[9]

But this is no military dictatorship. If it were, Carlos Lacerda would never be allowed to say the things he says. Everything in Brazil is free — but controlled.

Castelo Branco, through extra-constitutional decrees dubbed "Institutional Acts" (Portuguese: "Ato Institucional" or "AI"), Castelo Branco gave the executive the unchecked ability to change the constitution and remove anyone from office ("AI-1") as well as to have the presidency elected by Congress. A two-party system was created - the ruling government-backed National Renewal Alliance (ARENA) and the mild not-leftist opposition Brazilian Democratic Movement (MDB) party ("AI-2").[11] In the new Constitution of 1967 the name of the country was changed from Republic of the United States of Brazil to Federative Republic of Brazil.

تصلب النظام، كوستا إ سيلڤا

مقالة مفصلة: آرتور دا كوستا إ سيلڤا

مقالة مفصلة: آرتور دا كوستا إ سيلڤا

AI-5

ردود الفعل والمظاهرات

سنوات الرصاص، ميديتشي (1969-1974)

مقالة مفصلة: إميليو گاراستازو ميديتشي

مقالة مفصلة: إميليو گاراستازو ميديتشي

المقاومة

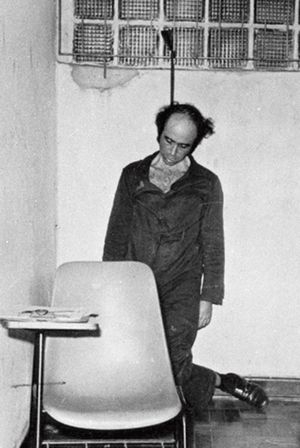

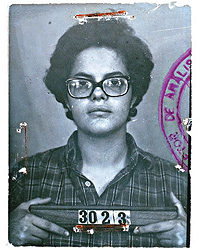

التعذيب

الحظر والسيطرة الاجتماعية

مقالة مفصلة: الحظر في البرازيل

مقالة مفصلة: الحظر في البرازيل

الطلاب الناشطون

احتلال جامعة برازيليا

الاضطهاد السياسي

الكفاح المسلح للحركات اليسارية

مقالة مفصلة: الكفاح المسلح لليسار في البرازيل

مقالة مفصلة: الكفاح المسلح لليسار في البرازيل

الأفعال الرئيسية

ادارة گايزل، distensão، وصدمة النفط 1973

It was in this atmosphere that retired General Ernesto Geisel (1974–79) was elected to Presidency with Médici's approval. Geisel was a well-connected Army General and former president of Petrobras.

الاقتصاد

مقالة مفصلة: المعجزة الاقتصادية البرازيلية

مقالة مفصلة: المعجزة الاقتصادية البرازيلية

President Geisel sought to maintain high economic growth rates of the Brazilian Miracle which were tied to maintaining the prestige of the regime, even while seeking to deal with the effects of the 1973 oil crisis. Geisel removed long-time Minister of Finance Antônio Delfim Netto. He maintained massive state investments in infrastructure—highways, telecommunications, hydroelectric dams, mineral extraction, factories, and atomic energy. All this required more international borrowing and increased state's debt.

Fending off nationalist objections, he opened Brazil to oil prospecting by foreign firms for the first time since the early 1950s.[بحاجة لمصدر] He also tried to reduce Brazil's reliance on oil, by signing a 10 billion USD agreement with West Germany to build eight nuclear reactors in Brazil.[13] During this time ethanol production program was promoted as an alternative to gasoline and the first ethanol fueled cars were produced.

Brazil suffered drastic reductions in its terms of trade as a result of the 1973 oil crisis. In the early 1970s, the performance of the export sector was undermined by an overvalued currency. With the trade balance under pressure, the oil shock led to a sharply higher import bill. Thus, the Geisel government borrowed billions of dollars to see Brazil through the oil crisis. This strategy was effective in promoting growth, but it also raised Brazil's import requirements markedly, increasing the already large current-account deficit. The current account was financed by running up the foreign debt. The expectation was that the combined effects of import substitution industrialization and export expansion eventually would bring about growing trade surpluses, allowing the service and repayment of the foreign debt.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Brazil shifted its foreign policy to meet its economic needs. "Responsible pragmatism" replaced strict alignment with the United States and a worldview based on ideological frontiers and blocs of nations. Because Brazil was 80% dependent on imported oil, Geisel shifted the country from uncritical support of Israel to a more neutral stance on Middle Eastern affairs. His government also recognized the People's Republic of China and the new socialist governments of Angola and Mozambique, both former Portuguese colonies. The government moved closer to Latin America, Europe, and Japan.

Brasil's intention to build nuclear reactors with West Germany's help created tensions with the US which did not want to see a nuclear Brazil. After election of Carter a greater emphasis was put on the human rights. The new Harkin Amendment limited American military assistance to countries with human rights violations. Brazilian right-wingers and military viewed this as incursion on Brazilian sovereignty and Geisel renounced any future military aid from United States in April 1977.[14]

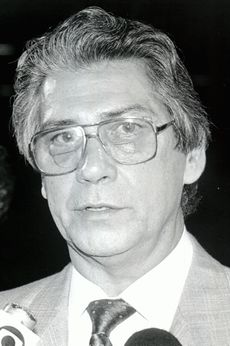

الانتقال للديمقراطية، فيگيردو

مقالة مفصلة: جواو باتيستا فيگيردو

مقالة مفصلة: جواو باتيستا فيگيردو

الرئيس جواو فيگيردو steered the country back to democracy and promoted the transfer of power to civilian rule, facing opposition from hardliners in the military. فيگيردو كان جنرالاً في الجيش والرأس السابق لـمصلحة المخابرات الوطنية البرازيلية.

انهيار النظام

العلاقات الخارجية

خط زمني

- April 1964 - the coup.

- October 1965 - political parties abolished, creation of two party system.

- October 1965 - Presidential elections to be indirect.

- January 1967 - a new Constitution.

- March 1967 - Costa e Silva takes office.

- November 1967 - opposition starts armed resistance.

- March 1968 - beginning of student protests.

- December 1968 - Institutional Act Nr.5.

- September 1969 - Medici selected as President.

- October 1969 - a new Constitution.

- January 1973 - armed resistance suppressed.

- June 1973 - Medici announces Geisel as his successor.

- March 1974 - Geisel takes office.

- August 1974 - political relaxation announced.

- November 1974 - MDB wins in Senate elections.

- April 1977 - National Congress dismissed.

- October 1977 - Head of the Armed Forces dismissed.

- January 1979 - Institutional Act Nr. 5 dismissed.

- March 1979 - Figueiredo takes office.

- November 1979 - two party system of ARENA and MDB ended.

- November 1982 - opposition wins Lower house of Parliament.

- April 1984 - amendment for direct Presidential elections defeated.

- March 1985 - Jose Sarney takes office.

انظر أيضاً

- الانقلاب البرازيلي 1964

- Operation Condor

- History of ethanol fuel in Brazil

- Nuclear activities in Brazil

- Corinthians Democracy

- Films depicting Latin American military dictatorships

الهامش

- ^ Document No. 12. U.S. Support for the Brazilian Military Coup d’État, 1964

- ^ أ ب Gonzalez, Eduardo (December 6, 2011). "Brazil Shatters Its Wall of Silence on the Past". International Center for Transitional Justice. Retrieved Mar 18, 2012.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/485946/Janio-da-Silva-Quadros

- ^ Political turmoil

- ^ "Kennedy in 1963 considered a military intervention in Brazil; a coup followed in 1964". 8 January 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ BRAZIL MARKS 40th ANNIVERSARY OF MILITARY COUP

- ^ Brazil Marks 50th Anniversary of Military Coup

- ^ BRAZIL Toward Stability, TIME Magazine, December 31, 1965

- ^ أ ب MILITARY INTERVENTION AND DICTATORSHIP

- ^ "A Troubling Trend in Brazil". Youngstown Vindicator at Google News archive. September 17, 1967.

- ^ The Political Party System

- ^ خطأ في استخدام قالب template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified

- ^ Ernesto Geisel, 88, Is Dead; Eased Military Rule in Brazil

- ^ Geisel

المصادر

- Kirsch, Bernard (1990). Revolution in Brazil. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-19-506316-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

للاستزادة

- The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil 1964-1985, by Thomas E. Skidmore (1988).

- The Political System of Brazil: Emergence of a "Modernizing" Authoritarian Regime, 1964–1970, by Ronald M. Schneider (1973).

- The Military in Politics: Changing Patterns in Brazil, by Alfred Stepan (1974).

- Brazil and the Quiet Intervention: 1964, by Phyllis R. Parker (1979).

- Mission in Mufti: Brazil's Military Regimes, 1964–1985, by Wilfred A. Bacchus (1990).

- Eroding Military Influence in Brazil: Politicians Against Soldiers, by Wendy Hunter (1997).

أفلام تسجيلية

- Beyond Citizen Kane by Simon Hartog (1993)

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2014

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Brazilian military government

- 1960s in Brazil

- 1970s in Brazil

- 1980s in Brazil

- 20th century in Brazil

- دكتاتوريات عسكرية

- 1964 establishments in Brazil

- 1985 disestablishments in Brazil