پيرَّس من إپيروس

| Pyrrhus | |

|---|---|

تمثال نصفي رخامي لپيرَّس من ڤيلا البرديات في الموقع الروماني هركولانيوم، الآن في National Archaeological Museum of Naples، إيطاليا | |

| ملك إپيروس | |

| العهد | 297–272 BC[1] (العهد الثاني) |

| سبقه | Neoptolemus II |

| تبعه | Alexander II |

| العهد | 307–302 ق.م.[1] (أول عهد) |

| سبقه | Alcetas II |

| تبعه | Neoptolemus II |

| ملك مقدونيا | |

| العهد | 274–272 ق.م. |

| سبقه | Antigonus II |

| تبعه | Antigonus II |

| العهد | 288–285 ق.م.

المعارك |

| سبقه | Demetrius I |

| تبعه | Antigonus II |

| طاغية سيراقوسة | |

| العهد | 278–276 ق.م. |

| سبقه | Thinion & Sosistratus |

| تبعه | هيرو الثاني |

| وُلِد | ح. 319 ق.م. إپيروس، اليونان |

| توفي | 272 ق.م. (عن عمر 46) أرگوس، المورة، اليونان |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال |

|

| الأسرة الحاكمة | Aeacidae |

| الأب | Aeacides |

| الأم | Phthia |

| الديانة | الهلينية |

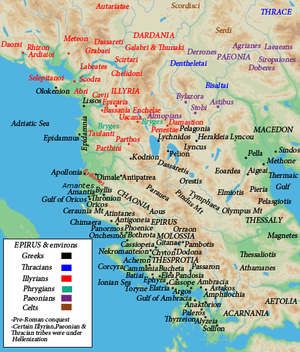

پيرَّس ( Pyrrhus ؛ /ˈpɪrəs/؛ باليونانية: Πύρρος Pýrrhos 318 - 272 ق.م.)، كان ملكاً يونانياً وأحد أبرز رجال الدولة في الفترة الهلينية ، وكان كذلك من أقوى المعارضين في عهد روما القديمة.[2][3][4][5][6] He was king of the Greek tribe of Molossians,[5][7] of the royal Aeacid house,[8] and later he became king (Malalas also called him toparch[9]) of Epirus. He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome, and had been regarded as one of the greatest generals of antiquity.[10] Several of his victorious battles caused him unacceptably heavy losses, from which the term "Pyrrhic victory" was coined.

Pyrrhus became king of Epirus in 306 BC at the age of 13, but was dethroned by Cassander four years later. He saw action during the Wars of the Diadochi and regained his throne in 297 BC with the support of Ptolemy I Soter. During what came to be known as the Pyrrhic War, Pyrrhus fought Rome at the behest of Tarentum, scoring costly victories at Heraclea and Asculum. He proceeded to take over Sicily from Carthage but was soon driven out, and lost all his gains in Italy after the Battle of Beneventum in 275 BC.

Pyrrhus seized the Macedonian throne from Antigonus II Gonatas in 274 BC and invaded the Peloponnese in 272 BC. The Epirote assault on Sparta was thwarted, however, and Pyrrhus was killed during a street battle at Argos.

أصل الاسم

The Latinized Pyrrhus derives from the Greek Pyrrhos (/ˈpɪrəs/; باليونانية: Πύρρος), meaning redhaired, redheaded or flame-colored.[11] Pyrrhos was also used as an alternate name for Neoptolemus, son of Achilles and the princess Deidamia in Homeric Greek mythology.[11]

الأصل

كان بيرس يدعي أنه من سلالة البطل أخيل ، وكان وسيماً ، شجاعاً ، وحاكماً مستبداً، ولكنه محبوب. وكان رعاياه يعتقدون أن في مقدوره أن يشفيهم من مرض الطحال بوضع قدمه اليمنى على ظهورهم وهم مستلقون على الأرض ، ولم يكن هو يأبى هذا العلاج على أفقر فقير في البلاد.

النشأة

In c. 319 BC, Pyrrhus was born to prince Aeacides of Epirus,[12] and Phthia, a Thessalian noblewoman, the daughter of the Thessalian general Menon. Aeacides was a cousin of Olympias, making Pyrrhus a second cousin to Alexander the Great. He had two sisters: Deidamia and Troias. In 319/318 BC, Arrybas, Aeacides' father and the regent of Epirus, died leaving Epirus to the joint kings Aeacides and Neoptolemus.

Aeacides supported Olympias in her fight against Cassander and marched on Macedon. In 317 BC, when Pyrrhus was only two, Olympias requested Aeacides' support yet again and he marched on Macedon a second time. Many of his soldiers did not like their service and mutinied. Aeacides released these soldiers from his army, but as a result his army was too small to achieve anything. When the mutineers arrived in Epirus they caused a rebellion against their absent king and Aeacides was dethroned. Cassander sent one of his generals, Lyciscus, to act as regent to the still underaged Neoptolemus. Epirus in effect became a puppet kingdom of Cassander. Pyrrhus' family fled north and took refuge with Glaukias of the Taulantians, one of the largest Illyrian tribes.[6] Pyrrhus was raised by Beroea, Glaukias' wife, a Molossian of the Aeacidae dynasty.[4][13] Cassander marched against Glaukias, defeated his army and captured Apollonia. Glaukias had to promise not to act against Cassander, but he refused to give up Pyrrhus and his family.[14]

By 313 BC, Cassander was distracted by his war against Antigonus Monophthalmus, one of the most powerful of the Diadochi. Fearing an invasion from Asia Minor, where Antigonus was building up his forces, he shifted his attention from west to the east. Aeacides took advantage of the situation and returned to Epirus. He appears to have regained popularity and raised a large army. Cassander sent an army under his brother Philip who defeated Aeacides in two battles. Aeacides was wounded in the last battle and died soon after.[14]

العهد الأول

In 307 BC, Glaukias invaded Epirus and put Pyrrhus on the throne. Pyrrhus was only eleven years old, so his guardians ruled in his stead until he came of age.[15] When he was seventeen he travelled to the court of Glaukias in Illyria to attend the wedding of one of Glaukias' sons. While he was in Illyria the Molossians rose in rebellion, drove out Pyrrhus' supporters, and returned Neoptolemus to the throne. This time Glaukias was unable to help him.[16]

المنفى

Pyrrhus travelled to the Peloponnese and served his brother-in-law Demetrius Poliorcetes who had married his sister Deidamia, and who was campaigning against Cassander in southern Greece.

معركة إپسوس

In 302 BC, Demetrius took his army to Asia Minor to support his father Antigonus Monophthalmus. Pyrrhus impressed Antigonus for he is reputed to have said that Pyrrhus would become the greatest general of his time, if he lived long enough.[17]

Antigonus had grown too powerful and the other successors, Seleucus, Lysimachus, Ptolemy and Cassander, had united against him. Lysimachus and Seleucus, reinforced by two of Cassander's armies, had concentrated their forces in Asia Minor and marched on Antigonus. Both armies met at Ipsus in Phrygia. The Battle of Ipsus was the largest and most important battle of the Wars of the Successors. Pyrrhus probably fought with Demetrius on the right wing, a place of honour, and made a brilliant display of valour among the combatants. Despite these brave efforts, Antigonus lost both the battle and his life. Demetrius, victorious on his wing, managed to escape with 9,000 men, and Pyrrhus continued to serve his brother-in-law as he started rebuilding Antigonus' empire.[18]

پطليموس

In 298 BC, Pyrrhus was taken hostage to Alexandria, under the terms of a peace treaty made between Demetrius and Ptolemy I Soter. There, he married Ptolemy I's stepdaughter Antigone (a daughter of Berenice I of Egypt from her first husband Philip—respectively, Ptolemy I's wife and a Macedonian noble). In 297 BC, Cassander died and Ptolemy, always looking for allies, decided to help restore Pyrrhus to his kingdom. He provided Pyrrhus with men and funds and sent him back to Epirus.[19]

العهد الثاني

Pyrrhus returned to Epirus at the head of an army, but not willing to fight a civil war he agreed to rule Epirus together with Neoptolemus. Soon both kings started to plot against one another. Pyrrhus was informed of a plot against his life and decided to strike first. He invited his fellow king to a dinner and had him murdered. The act does not appear to have been unpopular as Epirus' nobility seem to have been devoted to him.[20]

In 295 BC, Pyrrhus transferred the capital of his kingdom to Ambracia. In 292 BC, he went to war against his former ally and brother-in-law Demetrius by invading Thessaly while Demetrius was besieging Thebes. Demetrius responded immediately; he left the siege to his son Antigonus Gonatas and marched back north at the head of a large army.[21] Pyrrhus, outnumbered, withdrew to Epirus.[22]

While he was back in Epirus, Pyrrhus suffered another setback. His second wife, Lannasa, daughter of Agathocles of Syracuse the self-proclaimed king of Sicily, deserted him. She claimed that she, a daughter of a Greek king, could no longer bear to share her home with barbarian women. She fled to Corcyra with her dowry, offering it and herself to Demetrius. He accepted, sailed to the island and took possession of both Corcyra and Lannasa. After returning to his army in mainland Greece, Demetrius planned to invade Epirus. In 289 BC, he invaded Pyrrhus' allies, the Aetolian League, hoping to neutralize them before he invaded Epirus. The Aetolians refused battle and retreated into the hills. After ransacking the Aetolians' countryside, Demetrius left a strong force under his best general Pantauchus in Aetolia and marched on Epirus. Meanwhile, Pyrrhus had raised his army and was marching to the rescue of his Aetolian allies. The two armies, on different roads, passed one another and Demetrius started plundering Epirus while Pyrrhus met Pantauchus in battle.

Pyrrhus had the bulk of the army of Epirus with him, probably 20,000–25,000 men, while Pantauchus commanded but a detachment of Demetrius' army consisting of around 11,000 men. The fighting was heavy, and according to the sources Pantauchus and Pyrrhus sought out one another. Pantauchus challenged Pyrrhus to individual combat, and Pyrrhus accepted. After hurling spears at each other they fought it out with swords. Pyrrhus was wounded, but in return wounded his opponent twice, in the thigh and in the neck. Pantauchus' bodyguards had to carry him away. Emboldened by their king's victory, the Epirotes resumed their attack and broke Pantauchus' army, and took 5,000 prisoners. The army then honoured Pyrrhus by bestowing the surname of 'Eagle' upon him. Demetrius, upon hearing of Pyrrhus's victory, marched back to Macedon. Pyrrhus released his prisoners and marched back to Epirus.[23]

In 289 BC, Pyrrhus, learning that Demetrius was dangerously ill, invaded Macedonia. His original intention was merely to raid and pillage, but with Demetrius unable to lead his forces he met almost no opposition. Pyrrhus penetrated as far as the old Macedonian capital of Aegae before Demetrius was well enough to take the field. Since Demetrius commanded a superior force, Pyrrhus had no choice but to retreat.[24]

Demetrius, just as restless as Pyrrhus, planned to invade Asia and reclaim his father's old domains. He first made peace with Pyrrhus granting him his holdings in Macedonia while holding on to Corcyra and Leucas, then he started to raise a vast army and a huge fleet.[25] Faced with this threat, the other Diadochi Lysimachus, Ptolemy, and Seleucus allied against him. The three kings sent embassies to Pyrrhus trying to win him over to their side or at least get him to remain neutral. If the allies won and Pyrrhus remained neutral he would gain nothing. If on the other hand Demetrius would be victorious he could overwhelm Pyrrhus at any time in the future. Pyrrhus's personal enmity against Demetrius might have played an additional role in his decision to join the allies.[26]

In 288 BC, the allied kings began their campaigns against Demetrius. Ptolemy sailed against Demetrius's Greek allies with a large fleet. Lysimachus invaded upper Macedonia from Thrace. Pyrrhus waited until Demetrius had marched against Lysimachus and then invaded southern Macedonia. Demetrius must have thought that Pyrrhus would not renege on his treaty, because western and southern Macedonia fell without opposition. Meanwhile, Demetrius had won a victory over Lysimachus near Amphipolis. When the Macedonian army heard that their homeland was being overrun by Pyrrhus, they turned on Demetrius. They were fed up with his autocratic rule and grandiose plans and refused to advance any further. Demetrius then led his army against Pyrrhus, probably hoping that his Macedonians would be more willing to fight a foreign invader rather than Lysimachus, a veteran of Alexander. Unfortunately for Demetrius, his troops were so fed up with him that they deserted to Pyrrhus and he had to flee. Lysimachus was soon joined by Pyrrhus and they decided to share rulership over Macedonia.[27]

Demetrius gathered a new army in Greece and besieged Athens, which had rebelled against the puppet government he had installed. The Athenians called on Pyrrhus for assistance and he marched against Demetrius once more. This caused Demetrius to raise the siege. The Athenians thanked Pyrrhus by erecting a bust to him and allowing him into the city for the celebrations. However, they did not allow his army to enter the city, probably fearing Pyrrhus would install a garrison and make himself overlord of Athens. Pyrrhus made the most of the situation and advised the Athenians never to let a king enter their city again.[28]

Pyrrhus and Demetrius made peace once more but, like all previous agreements, it did not last. When Demetrius, in 286 BC, invaded Asia in order to attack Lysimachus's Asian domains, Lysimachus requested that Pyrrhus invade Thessaly and from there attack Demetrius' garrisons in Greece. Pyrrhus agreed, probably in order to keep his fractious Macedonian troops busy and less likely to rebel and also to gain an easy victory over the weakened Antigonids.[29] He quickly defeated Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius's son, who ceded Thessaly to him in order to make peace. Pyrrhus's Greek Empire was now at its zenith: he ruled an enlarged Epirus, half of Macedonia, and Thessaly.[28]

In 285 BC, Demetrius was defeated by Seleucus. This freed the hands of Lysimachus who decided to get rid of his co-ruler in Macedonia. He first isolated Pyrrhus from his traditional ally the Ptolemies, by marrying Arsinoe II, the sister of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. He also made a large donation to the Aetolians, Pyrrhus's main allies in Greece. Pyrrhus felt threatened enough to make an alliance with Antigonus Gonatas. In 284 BC, Lysimachus invaded Pyrrhus's half of Macedonia with a huge army.[30] Unable to stand against Lysimachus's superior army Pyrrhus retreated and linked up with Antigonus Gonatas. Lysimachus started a propaganda campaign in which he appealed to the patriotism of the Macedonians serving Pyrrhus. He reminded them that Pyrrhus was in fact a foreign king while he himself was a true Macedonian. The campaign was successful. With his Macedonian troops turning against him Pyrrhus had no other choice but to withdraw to Epirus. Lysimachus invaded and plundered Epirus the following year. Pyrrhus did not oppose Lysimachus for he was probably fighting a war in Illyria to the north. According to Pausanius, "Pyrrhus was roaming around as usual".[31]

الصراع مع روما

السبب الرئيسي الذي يسّر للرومان فتح بلاد اليونان كان انحلال الحضارة اليونانية من الداخل؛ ذلك أنه ما من أمة عظيمة قد غلبت على أمرها إلا بعد أن دمرت هي نفسها. وقد دمرت بلاد اليونان نفسها بتقطيع غاباتها ، وإتلاف تربتها ، واستنفاد ما في باطن أرضها من معادن ثمينة ، وبتحول طرق التجارة عنها، واضطراب الحياة الاقتصادية نتيجة لاختلال النظام السياسي ، وفساد الديمقراطية وانحلال الأسر الحاكمة، وفساد الأخلاق، وانعدام الروح الوطنية، ونقص السكان وتدهور قوتهم الجسمية، واستبدال الجنود المرتزقة بالجيوش الوطنية، وما أدت إليه الحروب الأهلية من تطاحن بين الإخوة وإتلاف لموارد البلاد، والقضاء على الكفايات بالفتن المتضادة الصماء- كل هذه قد استنفدت موارد هلاس في الوقت الذي كانت فيه الدولة الصغيرة القائمة على ضفة نهر التيبر ،

والتي كانت تحكمها أرستقراطية صارمة بعيدة النظر، تدرب جحافلها القوية المجندة من طبقة الملاك ، وتتغلب على جيرانها ومنافسيها ، وتستولي على ما في البحر الأبيض المتوسط من طعام ومعادن، وتزحف عاماً فعاماً على المستعمرات اليوناني في جنوبي إيطاليا. لقد كانت هذه المحلات القديمة في سابق عهدها تزهو بثرائها ، وحكمائها ، وفنونها ، ولكنها الآن قد أفقرتها الحروب وغارات ديونيشيوس وسلبه ونهبه، ونشأة روما وتقدمها ومنافستها لهذه المستعمرات في مركزها التجاري. يضاف إلى هذا أن القبائل الأصلية التي كان اليونان قد استعبدوا أفرادها أو طردوهم إلى ما وراء حدودها، قد ازدادت وتضاعفت ، في الوقت الذي كان سادتها ينشدون النعيم والراحة بقتل أطفالهم وإسقاط الحاملات من نسائهم؛ وما لبث السكان الأصليين أن أخذوا ينازعون المستعمرين السيطرة على جنوبي إيطاليا ، واستغاثت المدن الإيطالية بروما فأغاثتها والتهمتها.

وخشيت تاراس بأس روما النامية فاستعانت بملك إبيروس الشاب الجري ء؛ وكانت الثقافة اليونانية قد امتدت إلى هذه البلاد الجبلية الجميلة المعروفة إلينا باسم ألبانيا الجنوبية ، منذ أن شاد الدوريون معبد زيوس في دودونا Dodona ، ولكن هذه الثقافات ظلت مزعزعة غير موطدة الأركان . حتى عام 295 حين تولى بيرس Pyrrhus ملك الملوسيين Mollosians وهم أقوى القبائل الإبيروسية وأعظمها سلطاناً.

ولما استغاث بهِ أهل تارنتم رأى في هذا فرصة له مغرية: فقد قدر أنه يستطيع فتح روما، وهي الخطر الذي يتهدده من الغرب ، كما فتح الإسكندر بلاد الفرس وهي الخطر الذي كان يتهدده من الشرق، فيثبت بذلك نسبه ببسالته. ولهذا عبر البحر (الأدرياوي) في عام 281 على رأس قوة مؤلفة من 25.000 من المشاة ، وثلاثة آلاف من الفرسان وعشرين فيلاً.

مفاوضات الصلح

كان اليونان قد أخذوا الفيلة كما أخذوا التصوف عن الهند. والتقى بالرومان عند هرقلية Heracleia ، وانتصر عليهم "نصراً بيرسياً": أي أن خسارته في هذا النصر كانت عظيمة ، وأن موارده من الرجال والعتاد قد نقصت إلى حد جعله يرد على أحد أعوانه حين هنأه به بهذه العبارة التي أضحت مثلاً سائراً مدى الأجيال إذ قال إن نصراً آخر مثله كفيل بأن يقضي عليه. وأرسل الرومانكيس فبريسيوس ليفاوضه في أمر تبادل الأسرى. ويروي أفلوطرخس ما دار وقتئذ من الحديث فيقول:

وفي أثناء العشاء دار الحديث حول كثير من الشؤون، وكان أهمها كلها شؤون بلاد اليونان وفلاسفتها. وتحدث قنياس Cineas (الدبلوماسي الإبيروسي) عن أبيقور ، وأخذ يشرح آراء أتباعه في الآلهة، والدولة، وأغراض الحياة، مؤكداً أن اللذة أكبر سعادة للإنسان؛ ووصف الشؤون العامة بأن لها أسوأ الأثر في الحياة السعيدة لأنها تسبب لها الاضطراب. وقال إن الآلهة لا شأن لها بنا جميعاً ولا تعني بنا أية عناية، فهي مجردة من الرحمة بنا أو الغضب علينا ، وهي تحيا حياة لا تقوم فيها بعمل وتقضيها في النعيم والترف. وقبل أن ينتهي قنياس من كلامهِ صاح فبرسيوس قائلاً لبيرس "إي هرقل! دع بيرس والسمنيين يمتعون أنفسهم بمثل هذه الآراء ما داموا في حرب معنا".

حرب للنهاية

تأثر بيرس بما رآه من صفات الرومان ، فدعاه هذا كما دعاه يأسه من تلقي العون الكافي من يونان إيطاليا ، إلى أن يرسل قنياس إلى روما ليفاوضها في الصلح. وأوشك مجلس الشيوخ أن يوافق على هذا، ولكنه فوجئ بأبيوس كلوديوس Appius Claudius، وكان أعمى يشرف على الموت، يحمل إليه ليحتج على عقد الصلح مع جيش أجنبي في أرض إيطالية. فلما عجز بيرس عن نيل بغيته اضطر أن يواصل الحرب، وانتصر انتصاراً انتحارياً آخر في أسكولوم Asculum، ثم عاوده اليأس من الفوز على روما فعبر البحر إلى صقلية معتزماً أن يخلصها من القرطاجيين. وفيها صد القرطاجيين ببطولتهِ المتهورة، ولكن يونان صقلية كانوا أجبن من أن يخفوا لنجدتهِ، أو لعله كان يحكمهم حكماً استبدادياً كما يحكم كل طاغية.

وسواء كان هذا أو ذاك هو السبب فإن أهل صقلية لم يمدوه بما يحتاجه من العون، فاضطر إلى ترك الجزيرة بعد أن ظل يحارب فيها ثلاث سنين. ونطق وهو يغادر بنبوءتهِ المأثورة: "أي ميدان قتال اتركه لقرطاجة وروما!" ولما وصل إلى إيطاليا كانت قواته قد نقصت نقصاً كبيراً، فهزم في بنفنتوم Beneventum (275)، حيث أثبتت الكتائب المتحركة الخفيفة السلاح لأول مرة تفوقها على الصفوف المتراصة الحركة، فكان ذلك بداية مرحلة جديد في تاريخ الحروب. وعاد إلى إبيروس ، كما يقول الفيلسوف أفلوطرخس: "بعد أن قضى في هذه الحروب ست سنين؛ ومع أنه قد أخفق في أغراضهِ فقد احتفظ بشجاعة لم تنل منها كل هذه المصائب، ويضعه الناس لكثرة تجاربهِ الحربية، وبأسهِ، وجرأتهِ، في منزلة أعلى من منزلة سائر أمراء عصره. ولكن الذي ناله بشجاعتهِ قد خسره مرة أخرى بسبب آماله المتطرفة؛ وكانت رغبته في نيل ما لا يملك سبباً في ضياع ما كان يملك".

واشتبك بيرس وقتئذ في حروب جديدة ثم قتل بقرميدة ألقتها عليه عجوز في أرگوس. واستسلمت تراس لرومة في تلك السنة نفسها.

الذكرى

In his Life of Pyrrhus, Plutarch records that Hannibal ranked him as the greatest commander the world had ever seen,[4] though in the Life of Titus Quinctius Flamininus, Plutarch writes that Hannibal placed him second after Alexander the Great. This latter account is also given by Appian.[32] While he was a mercurial and often restless leader, and not always a wise king, he was considered one of the greatest military commanders of his time.

Pyrrhus was known for his benevolence. As a general, Pyrrhus's greatest political weaknesses were his failures to maintain focus and to maintain a strong treasury at home (many of his soldiers were costly mercenaries).

The concept of a monarch having a touch that could heal all wounds may have originated with Pyrrhus. As Pliny the Elder states, Pyrrhus' great toe on his right foot cured diseases of the spleen by merely touching the patient. His toe could also not be burned so when his body was cremated, his toe was put in a coffer, and kept at an unknown temple.[33]

Pyrrhus lends his name to the term "Pyrrhic victory" which stems from statement he is alleged to have made following the Battle of Asculum. In response to congratulations for winning a costly victory over the Romans, he is reported to have said: "If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined".[34] The term Pyrrhic Victory has therefore come to signify a victory that was won at such cost that it loses all worth.

Pyrrhus and his campaign in Italy provided the Greek world with an opportunity to check the advance of Rome further into the Mediterranean. The failure to fully exploit this opportunity while Rome was still only an Italian regional power had immense consequences. The conquest of Magna Graecia by the Romans brought them into direct competition with Carthage, ultimately leading to the First Punic War. Rome's victory in this conflict arguably transformed it from a regional power to one of the most powerful states in the Mediterranean. Over the next century the failure of the various Kingdoms and city states of the Hellenistic world to put on a united front against Rome resulted in their absorption into the Roman Empire or, in the case of some, the reduction to the status of a Roman client state. By 197 BC, Macedonia and many southern Greek city-states became Roman client states; in 188 BC, the Seleucid Empire was forced to cede most of Asia Minor to Rome's ally Pergamon (Pergamum). In 133 BC Attalus III, the last King of Pergamon (excluding the pretender Eumenes III), bequeathed the Kingdom and its considerable territories in Asia Minor to Rome in his will. At the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC Rome defeated the city-state of Corinth and its allies in the Achaean League. The league was dissolved and Rome took formal possession of the territoires which constitute modern day Greece, re-organising these territories into province of Macedonia.[35] Finally, in 63 BC, Pompey Magnus delivered the final coup de grace to the already much reduced Seleucid Empire, deposing its last ruler and absorbing its territories into the new Roman province of Syria.

Pyrrhus wrote memoirs and several books on the art of war. These have since been lost, although, according to Plutarch, Hannibal was influenced by them,[4] and they received praise from Cicero.[36]

Pyrrhus was married five times: his first wife Antigone bore him a daughter called Olympias and a son named Ptolemy in honour of her stepfather. She died in 295 BC, possibly in childbirth, since that was the same year her son was born.[37] His second wife was Lanassa, daughter of King Agathocles of Syracuse (r. 317–289 BC), whom he married in about 295 BC; the couple had two sons, Alexander[37] and Helenus; Lanassa left Pyrrhus. His third wife was the daughter of Audoleon, King of Paeonia; his fourth wife was the Illyrian princess Bircenna, who was the daughter of King Bardylis II (r. c. 295–290 BC); and his fifth wife was the daughter of Ptolemy Keraunos, whom he married in 281/280 BC.

المصادر

ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Sampson, Gareth C. (2020-08-05). Rome & Parthia: Empires at War: Ventidius, Antony and the Second Romano-Parthian War, 40–20 BC (in الإنجليزية). Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-5267-1015-4.

- ^ Hackens 1992, p. 239; Grant 2010, p. 17; Anglin & Hamblin 1993, p. 121; Richard 2003, p. 139; Sekunda, Northwood & Hook 1995, p. 6; Daly 2003, p. 4; Greene 2008, p. 98; Kishlansky, Geary & O'Brien 2005, p. 113; Saylor 2007, p. 332.

- ^ Hammond 1967, pp. 340–345; Hammond has argued convincingly that the Epirotes were a Greek-speaking people.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Plutarch. Parallel Lives, "Pyrrhus".

- ^ أ ب Encyclopædia Britannica ("Epirus") 2013.

- ^ أ ب Encyclopædia Britannica ("Pyrrhus") 2013.

- ^ Borza 1992, p. 62.

- ^ Jones 1999, p. 45; Chamoux 2003, p. 62; American Numismatic Society 1960, p. 196.

- ^ Malalas, Chronography, § 8.208

- ^ Milton, John and W. Bell. 1890. Milton's L'allegro, Il Penseroso, Arcades, Lycidas, Sonnets Etc. London and New York: Macmillan and Co, p. 168; Smith, William. 1860. A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, p. 729; Tytler, Alexander Fraser. 1823. Elements of General History. Concord, NH: Isaac Hill, p. 102.

- ^ أ ب O'Hara 2017, p. 106.

- ^ At Pyrrhus' birth in 319 BC, Aeacides was only a prince and his father, Arrybas, ruled Epirus as a regent to the underaged King Neoptolemus.

- ^ Wilkes 1992, p. 124.

- ^ أ ب Champion 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Justin, Epitome, 17.3.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 14; Glaukias' kingdom was being attacked by pirates.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Champion 2009, pp. 14–17.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Plutarch. Life of Pyrrhus, 5.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 32; Demetrius commanded the full might of the Macedonian army which at that particular time was much larger than the army of Epirus.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Champion 2009, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Champion 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Reputedly raising 110,000 soldiers and 500 ships.

- ^ Champion 2009, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Champion 2009, pp. 35–36.

- ^ أ ب Champion 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Plutarch. Pyrrhus, 12; Plutarch. Demetrius, 41.

- ^ In 301 BC, at the Battle of Ipsus, Lysimachus had fielded 40,000 troops. Since then he had acquired half of Macedonia and western Asia Minor. With these combined assets his army could have numbered over 70,000 troops. Pyrrhus commanded 40,000 troops at best.

- ^ Champion 2009, pp. 37–39; Greenwalt 2010, p. 298: "From 288 until 284, Pyrrhus and Lysimachus shared the rule of Macedonia until the latter drove the former back to Epirus (Plut., Pyrrhus 7–12)."; Pausanius. Guide to Greece, 1.7.

- ^ Appian. History of the Syrian Wars, §10 and §11.

- ^ Pliny, Naturalis Historia, 2.111

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPlutarch21.9 - ^ Pausanias, 7.16

- ^ Tinsley 2006, p. 211.

- ^ أ ب Bennett 2010.

| سبقه Alcetas II |

ملك إپيروس 307–302 ق.م. |

تبعه Neoptolemus II |

| سبقه Neoptolemus II |

ملك إپيروس 297–272 ق.م. |

تبعه الإسكندر الثاني |

| سبقه Demetrius I Poliorcetes |

ملك مقدون مع لوسيماخوس 288–285 ق.م. |

تبعه Antigonus II Gonatas |

| سبقه Antigonus II Gonatas |

ملك مقدون 274–272 ق.م. |

تبعه Antigonus II Gonatas |

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- پيرَّس من إپيروس

- حكام إپيروس القديمة

- ملوك مقدونيون

- Ancient Epirotes

- جنرالات يونانيون قدماء

- Non-dynastic kings of Macedon

- Ancient Epirotes in Macedon

- حكام أطفال قدماء

- حكام القرن الثالث ق.م.

- حكام القرن الرابع ق.م.

- كتاب عسكريون يونانيون قدماء

- مقدونيا الهلنية

- يونانيو القرن الرابع ق.م.

- يونانيو القرن الثالث ق.م.

- يونان قديمة

- قادة يونان

- إغريق

- مواليد 318 ق.م.

- وفيات 272 ق.م.