المادية التاريخية

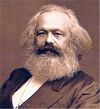

المادية التاريخية matérialisme historique هي مذهب فلسفي يعنى بدراسة الظواهر الاجتماعية والإنسانية في ضوء مبادئ التحليل الماركسي marxisme بصورة عامة، ومبادئ المادية الجدلية matérialisme dialectique المعنية بظواهر الكون والطبيعة بصورة خاصة، فهي تستمد من المادية الجدلية مبادئها في تحليل الظواهر والوقائع الاجتماعية، إذ تعتمد اعتماداً أساسياً على المقولات الثلاث الأساسية المتمثلة بأن عمليات التراكم الكمية تؤدي إلى تغيرات كيفية، وأن التناقض بين مكونات الأشياء يعد الأساس في حركتها- وما من شيء في الطبيعة والحياة الاجتماعية إلا ويحمل في مكوناته قدراً من التناقض ينتج صراعاً مستمراً بينها- وأن الصراع بين المكونات يؤدي باستمرار إلى ما يعرف بنفي النفي، فكل مرحلة من مراحل التطور تنفي بالضرورة المراحل السابقة، ولا يمكن أن تتعايش المراحل مع بعضها إلا لفترات مؤقتة توصف بالتناقض، ولايمكن أن يكون بينها أي وفاق أو استقرار.

المادية التاريخية هي نتاج تطبيق المنطق الجدلي على التطور التاريخي للمجتمع ، حيث يرى الماركسيون ان البناء الفوقي للمجتمع هو ناتج عن البناء التحتي ، و بالتالي تعتبر اخلاق المجتمع متأثرة بالعلاقات الاقتصادية ، فمثلا في بلد شيوعي لا يوجد وراثة فان الخلاف بين الاخوة على الارث غير موجود ، و مثل اخر ان المجتمع الزراعي تكون فيه الاسرة اكثر تماسك من اسرة مجمع برجوازي ، و يقول الشيوعيين ان الدليل على صحة النظرية في الواقع العربي قبل بدء اندثار الاعمال الزراعية وتقلص المجتمع الزراعي كان العمل يعيب الفتاة ، لكن بعد تقلص الحياة الزراعية و بدء حياة التجارة والصناعة اصبح اهم شرط لتجد الفتاة زوجاً، هو ان تكون موظفة ، رغم ان شيئاً لم يتبدل سوى وسائل الانتاج، ومازالت محور نقاش لم يحسم، رغم أن هذا الجزء من الماركسية هو الأكثر تقبلاً ، لدى الفلاسفة المثاليين ، و رجال الدين ، حيث جاء في توصيات رجال دين كاثوليك، انه يجب الاستفادة من الماركسية في فهم المجتمع، وذلك في مؤتمر ماذا بقي من الماركسية، الذي عقد في اسبانيا، عام 1998، لكن رغم ذلك مازالت الفلسفة المادية بشكل عام، موضع نقاش .

في جوهر المادية التاريخية أن البناء الفوقي للمجتمع هو ناتج البناء التحتي ، حيث أن البناء التحتي للمجتمع هو مجموع علاقات المجتمع الاقتصادية ، و البناء الفوقي هو القوانين و الأخلاق و السياسات العامة ، و تعتبر الماركسية أن البناء الفوقي للمجتمع يعكس بنائه التحتي ، فمثلا في المجتمع الرأسمالي تتولد دولة تخدم المصالح الرأسمالية و أحزاب لا تتناقض مع الرأسمالية و تسن القوانين بما يخدم الرأسمالية ، و الجدير ذكره في الابحاث العربية كانت تصل لنتيجة أن رجال الدين يحورون الدين لصالح الطبقة الحاكمة ، فمثلاً في مصر عبد الناصر تم دعم العلاقات الاشتراكية و التأميم و الإصلاح الزراعي ، و في مصر مبارك كانت الخصخصة و الانتقال لاقتصاد السوق كذلك مدعومة بغطاء ديني ، و يأخذ الماركسيون على الأديان خدمتها لمصالح الطبقة الحاكمة ، ففي العصور الوسطى أستعمل الدين المسيحي الذي يدعو للمحبة و التسامح ، غطاء لما سمي بالحروب الصليبية التي ارتكب فيها مجازر بحق المسيحين الشرقيين قبل المسلمين ، و يرى بعض المفكرين الشيوعيين أن النظام البروليتاري سوف يحمي الأديان من التحريف قبل أن تبدأ بالاضمحلال تلقائياً ، لأن المجتمع الشيوعي يعزل فيه الدين عن الدولة ، و تصبح الدولة ملكا للشعب حيث أن الدولة كذلك تبدأ بالتلاشي ،وفق نظام شيوعي متطور، و الدين يصبح للدين .

وينطبق الأمر على الظواهر الاجتماعية والتاريخ الإنساني، فيأخذ مفهوم التشكيلة الاقتصادية الاجتماعية أهمية كبيرة في دراسة المجتمع والتغير الاجتماعي، وينظر إليها على أنها بمنزلة النظام الذي يحدد في كل مرحلة تاريخية معطاة خصائص المجتمع وأبعاده وطبيعة المشكلات التي يعانيها الناس في ذلك الحين، إضافة إلى أنه يحدد أيضاً أنماط السلوك الإنساني وأشكال الفعل التي يمارسها الأفراد في كل مرحلة تاريخية.

إن التشكيلة الاجتماعية الاقتصادية التي تعدّ الأساس الذي تبني عليه المادية التاريخية تحليلاتها للمجتمع تتكون على الدوام من بناءين أساسيين هما البناء التحتي، ويتكون من قوى الإنتاج وعلاقات الإنتاج، وفيه يكمن سر التطور الإنساني للمجتمعات كافة، حيث توصف قوى الإنتاج بقابليتها للتطور المستمر، في حين تقع علاقات الإنتاج في تناقض مستمر مع قوى الإنتاج إلى أن تأخذ علاقات الإنتاج أنماطاً جديدة تتوافق فيها مع قوى الإنتاج، فتدخل التشكيلة الاقتصادية الاجتماعية في مرحلة جديدة من مراحل التطور، لكن مجمل البناء التحتي يدخل أيضاً في تناقض مع البناء الفوقي الذي يتكون من المؤسسات والنظم والمعايير والأخلاق والقيم والثقافة وغيرها من مكونات البناء الفوقي، وسرعان ما تجد مكونات البناء الفوقي نفسها مرة أخرى أسيرة للتغيرات في البناء التحتي ومدعوة لأن تأخذ أنماطاً جديدة تتوافق مع مرحلة التطور الجديدة.

ويظهر مفهوم التأثير المتبادل أو الجدلية في العلاقة بين العناصر المكونة للوحدة في تحليل العلاقة بين عناصر البناء الاجتماعي بمختلف مستوياته، منها العلاقة القائمة بين عناصر البناء الفوقي والقاعدة المادية الاقتصادية في المجتمع؛ إذ تؤدي التحولات المستمرة في القاعدة المادية إلى تغيرات مماثلة في البناء الفوقي، كما تسهم التغيرات الأخيرة أيضاً في تعزيز مسار التطور في عناصر القاعدة المادية، وتساعد على إحداث تطورات كيفية وكمية متعددة، مما يجعل العلاقة بين العنصرين قائمة على مبدأ التأثير المتبادل. وفي منحى آخر، وفي إطار القاعدة المادية الاقتصادية للمجتمع يلاحظ أن العلاقة بين عناصر هذه القاعدة تأخذ الشكل ذاته، فالتطور المستمر الذي يظهر في قوى الإنتاج يؤدي إلى إحداث تغيرات أيضاً في علاقات الإنتاج التي تعد بمنزلة الإطار الاجتماعي للقاعدة المادية التكنولوجية، لكن تطور قوى الإنتاج يسهم إسهاماً فعالاً في تحسين آلية العمل، وتحسين مستوى الإنتاج، وتطويره باستمرار، وعلى هذا تأخذ العلاقة بين عناصر القاعدة المادية الشكل نفسه، وتخضع لمبدأ التأثير المتبادل، فلا يمكن فهم تطور أحد العنصرين بمعزل عن العنصر الآخر، أو بمعزل عن التأثير الذي يمارسه هذا العنصر. وتتجلى وحدة العلاقة بين السبب والنتيجة أيضاً في طبيعة العلاقة بين عناصر البناء الفوقي الذي يجسد أفكار المجتمع وآدابه وفنونه وعقائده، إضافة إلى ما يتصل بالسلطة والدولة وغير ذلك، وفي هذا الإطار يسهم كل عنصر في التأثير في العنصر الآخر ويتلقى التأثير منه، وإنه لمن الصعوبة أن يعطى لأي عنصر من هذه العناصر دور المسبب أو دور المتأثر، لأنه في حقيقة الأمر يتجسد فيه المظهران بآن واحد.

إن الناس بتعبير ماركس Marx يدخلون ضمن سياق الإنتاج الذي يقومون به في علاقات محددة ومنفصلة عن رغباتهم، تتطابق مع مرحلة بعينها من مراحل تطور قوى الإنتاج المادية، ومن مجموع علاقات الإنتاج هذه يتكون التركيب الاقتصادي للمجتمع، الأساس الراسخ الذي يقوم عليه البناء القانوني والسياسي، والذي تترافق معه أنماط محددة من الوعي الاجتماعي، ويؤثر شكل الإنتاج في مجمل العمليات الاجتماعية والسياسية والروحية، فليس وعي الناس هو الذي يقرر شكل وجودهم وطبيعته، إنما وجودهم الاجتماعي هو الذي يقرر ويحدد أشكال وعيهم ومستوياته، فالظروف المعيشية المتماثلة التي تحيط بمجموعة من الأفراد تسهم في إيجاد مشاعر وأحاسيس متماثلة فيما بينهم، ومستويات وعي اجتماعي متقاربة يرتبط نموها بتغيرات الظروف المادية التي يعيشونها. ويصف كل من ماركس وإنغلز Engels في بيانهما الشيوعي مراحل تطور الطبقة العاملة ونموها بخطوطها الكبرى، ويظهر هذا الوصف كيفية تشكل الوعي من خلال تماثل الظروف الموضوعية المعطاة في مرحلة النمو الرأسمالي، إذ يؤدي الاتساع الكبير في استعمال الآلات وتقسيم العمل إلى خلق ظروف تجعل العامل ملحقاً بسيطاً بالآلة، فلا يطلب منه سوى القيام بأعمال بسيطة ورتيبة للغاية، فيؤدي تطور الصناعة الحديثة إلى جعل العمال يخضعون في المصانع لتنظيم أشبه ما يكون بالتنظيم العسكري، فهم بتعبير ماركس جنود الصناعة البسيطون، الخاضعون لسلسلة من كبار الضباط وصغارهم، وكأنهم في جيش عسكري.

ومع تقدم الصناعة ونموها يتزايد عدد العمال ويزداد تمركزهم، فتنمو قدراتهم، ويزداد إدراك العامل لهذه القدرات، وتسهم الظروف السيئة لأوضاعهم ومعيشتهم في اتحادهم وتشكيل الجمعيات التي تتضمن الدفاع عن مصالحهم ضد البرجوازية، وفي مرحلة متطورة من الصراع، وإزاء نمو الطبقة وتشكلها تأخذ جماعات كاملة من الطبقة الحاكمة بالتدهور نتيجة تطور الصناعة، وتتحول إلى صفوف الطبقة العاملة، وتحمل معها عناصر عديدة من الثقافة التي تغنيها بها.

ويشير ماركس في فلسفة نقد القانون عند هيغل Hegel إلى أنه ما أن تؤمن الجماهير بالنظرية وهي نتاج الوعي حتى تصبح قوة مادية توجه سلوكهم وممارساتهم، ويفسر ستالين Staline ذلك بأن الأفكار والنظريات التي تثيرها المهام الجديدة التي يوليها تطور الحياة المادية للمجتمع تشق طريقها وتصبح ملك الجماهير التي تعبئها وتنظمها ضد قوى المجتمع الزائلة، فتساعد بذلك على قلب هذه القوى التي تعوق تطور حياة المجتمع المادية.

وعلى الرغم من التحليلات الواسعة لدور الأفكار والنظريات في عملية التغيير فإن ذلك لا يعتمد على استقلالها، إنما ينطلق من ارتباطها بالشروط الموضوعية المعطاة أي بشروط الواقع. ففعالية الأفكار لا تخرج عن طبيعة الشروط التي ولدتها، إنما تخضع لها تمام الخضوع.

وما ينطبق في التحليل المادي التاريخي على مفهوم الوعي الاجتماعي، يندرج بدوره على دراسة الشخصية، فالإنسان دائماً ابن زمانه ومجتمعه وطبقته، فيتحدد جوهر الشخصية ويتضح تمام الوضوح بالمجتمع الذي تعيش فيه، وكل تشكيلة اجتماعية تضع قضية العلاقة بين المجتمع والشخصية على نحو مختلف وتحلها وفق نمط معين.

ولما كانت مراحل التطور تتمايز فيما بينها بالشروط الاقتصادية والاجتماعية السائدة فيها فمن الطبيعي أن تكون هناك أشكال متباينة للشخصية، وليس شكلاً واحداً. ففي مرحلة المشاعية البدائية لم يكن الإنسان بحسب تعبير ماركس قد انفصل عن الطبيعة، ولم يكن يعي ذاته إلا عضواً في جماعة معينة، وكان ذلك مرتبطاً بتخلف قوى الإنتاج وبدائيتها، ولكن مع تقدم القوى المنتجة، وفي شروط التقسيم الاجتماعي للعمل والملكية الخاصة لوسائل الإنتاج برز التباعد بين المصالح الشخصية، وظهرت أشكال الصراع، وبدأ الناس يدركون أنفسهم شخصيات، فنشأت الشخصية الطبقية بما يتوافق وطبيعة تلك المرحلة.

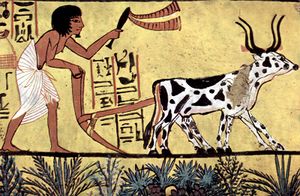

وبهذا النمط من التحليل تأخذ المادية التاريخية بدراسة مراحل التطور الاقتصادي والاجتماعي من مرحلة المشاعية البدائية التي لم تعرف فيها البشرية أي شكل من أشكال التملك، إلى مرحلة العبودية التي انتشرت فيها مظاهر تملك البشر بعضهم بعضاً، ومرحلة الإقطاعية التي سادت فيها ملكية الأرض، مع تقدم نسبي في حرية الإنسان بالمقارنة مع المرحلة السابقة، نتيجة تطور قوة الإنتاج، الأمر الذي استوجب ظهور علاقات إنتاجية جديدة، وأخيراً مرحلة التطور الرأسمالي التي انتشرت فيها أشكال جديدة من التملك لوسائل الإنتاج، مع تطور أكبر في مجالات العلم والتقانات، وتبشر المادية التاريخية بالمرحلة الشيوعية التي تعد آخر مرحلة من مراحل تطور البشرية التي تحمل في ثناياها مظاهر الصراع والتناقض لتصبح بعد ذلك خالية من أي تناقض داخلي.

أنماط الإنتاج

The main modes of production that Marx identified include primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, capitalism and communism. In each of these stages of production, people interact with nature and production in different ways. Any surplus from that production was distributed differently. Marx propounded that humanity first began living in primitive communist societies, then came the ancient societies such as Rome and Greece which were based on a ruling class of citizens and a class of slaves, then feudalism which was based on nobles and serfs, and then capitalism which is based on the capitalist class (bourgeoisie) and the working class (proletariat). In his idea of a future communist society, Marx explains that classes would no longer exist, and therefore the exploitation of one class of another is abolished.

الشيوعية البدائية

To historical materialists, hunter-gatherer societies, also known as primitive communist societies, were structured so that economic forces and political forces were one and the same. Societies generally did not have a state, property, money, nor social classes. Due to their limited means of production (hunting and gathering) each individual was only able to produce enough to sustain themselves, thus without any surplus there is nothing to exploit. A slave at this point would only be an extra mouth to feed. This inherently makes them communist in social relations although primitive in productive forces.

Ancient mode of production

Slave societies, the ancient mode of production, were formed as productive forces advanced, namely due to agriculture and its ensuing abundance which led to the abandonment of nomadic society. Slave societies were marked by their use of slavery and minor private property; production for use was the primary form of production. Slave society is considered by historical materialists to be the first-class society formed of citizens and slaves. Surplus from agriculture was distributed to the citizens, which exploited the slaves who worked the fields.[1]

Feudal mode of production

The feudal mode of production emerged from slave society (e.g. in Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire), coinciding with the further advance of productive forces. Feudal society's class relations were marked by an entrenched nobility and serfdom. Simple commodity production existed in the form of artisans and merchants. This merchant class would grow in size and eventually form the bourgeoisie. However, production was still largely for use.

Capitalist mode of production

The capitalist mode of production materialized when the rising bourgeois class grew large enough to institute a shift in the productive forces. The bourgeoisie's primary form of production was in the form of commodities, i.e. they produced with the purpose of exchanging their products. As this commodity production grew, the old feudal systems came into conflict with the new capitalist ones; feudalism was then eschewed as capitalism emerged. The bourgeoisie's influence expanded until commodity production became fully generalized:

The feudal system of industry, in which industrial production was monopolised by closed guilds, now no longer sufficed for the growing wants of the new markets. The manufacturing system took its place. The guild-masters were pushed on one side by the manufacturing middle class; division of labour between the different corporate guilds vanished in the face of division of labour in each single workshop.[2]

With the rise of the bourgeoisie came the concepts of nation-states and nationalism. Marx argued that capitalism completely separated the economic and political forces. Marx took the state to be a sign of this separation—it existed to manage the massive conflicts of interest which arose between the proletariat and bourgeoisie in capitalist society. Marx observed that nations arose at the time of the appearance of capitalism on the basis of community of economic life, territory, language, certain features of psychology, and traditions of everyday life and culture. In The Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels explained that the coming into existence of nation-states was the result of class struggle, specifically of the capitalist class's attempts to overthrow the institutions of the former ruling class. Prior to capitalism, nations were not the primary political form.[3] Vladimir Lenin shared a similar view on nation-states.[4] There were two opposite tendencies in the development of nations under capitalism. One of them was expressed in the activation of national life and national movements against the oppressors. The other was expressed in the expansion of links among nations, the breaking down of barriers between them, the establishment of a unified economy and of a world market (globalization); the first is a characteristic of lower-stage capitalism and the second a more advanced form, furthering the unity of the international proletariat.[5] Alongside this development was the forced removal of the serfdom from the countryside to the city, forming a new proletarian class. This caused the countryside to become reliant on large cities. Subsequently, the new capitalist mode of production also began expanding into other societies that had not yet developed a capitalist system (e.g. the scramble for Africa). The Communist Manifesto stated:

National differences and antagonism between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.

The supremacy of the proletariat will cause them to vanish still faster. United action, of the leading civilised countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.[6]

Under capitalism, the bourgeoisie and proletariat become the two primary classes. Class struggle between these two classes was now prevalent. With the emergence of capitalism, productive forces were now able to flourish, causing the industrial revolution in Europe. Despite this, however, the productive forces eventually reach a point where they can no longer expand, causing the same collapse that occurred at the end of feudalism:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. [...] The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property.[2]

Communist mode of production

Lower-stage of communism

The bourgeoisie, as Marx stated in The Communist Manifesto, has "forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians."[2] Historical materialists henceforth believe that the modern proletariat are the new revolutionary class in relation to the bourgeoisie, in the same way that the bourgeoisie was the revolutionary class in relation to the nobility under feudalism.[7] The proletariat, then, must seize power as the new revolutionary class in a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.[7]

Marx also describes a communist society developed alongside the proletarian dictatorship:

Within the co-operative society based on common ownership of the means of production, the producers do not exchange their products; just as little does the labor employed on the products appear here as the value of these products, as a material quality possessed by them, since now, in contrast to capitalist society, individual labor no longer exists in an indirect fashion but directly as a component part of total labor. The phrase "proceeds of labor", objectionable also today on account of its ambiguity, thus loses all meaning. What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society—after the deductions have been made—exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labor. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor cost. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.[8]

This lower-stage of communist society is, according to Marx, analogous to the lower-stage of capitalist society, i.e. the transition from feudalism to capitalism, in that both societies are "stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges." The emphasis on the idea that modes of production do not exist in isolation but rather are materialized from the previous existence is a core idea in historical materialism.

There is considerable debate among communists regarding the nature of this society. Some such as Joseph Stalin, Fidel Castro, and other Marxist-Leninists believe that the lower-stage of communism constitutes its own mode of production, which they call socialist rather than communist. Marxist-Leninists believe that this society may still maintain the concepts of property, money, and commodity production.[9]

مرحلة أعلى من الشيوعية

To Marx, the higher-stage of communist society is a free association of producers which has successfully negated all remnants of capitalism, notably the concepts of states, nationality, sexism, families, alienation, social classes, money, property, commodities, the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, division of labor, cities and countryside, class struggle, religion, ideology, and markets. It is the negation of capitalism.[10][11]

Marx made the following comments on the higher-phase of communist society:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life's prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs![8]

Continued development

In a foreword to his essay Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886), three years after Marx's death, Engels claimed confidently that "the Marxist world outlook has found representatives far beyond the boundaries of Germany and Europe and in all the literary languages of the world."[12] Indeed, in the years after Marx and Engels' deaths, "historical materialism" was identified as a distinct philosophical doctrine and was subsequently elaborated upon and systematized by Orthodox Marxist and Marxist–Leninist thinkers such as Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky, Georgi Plekhanov and Nikolai Bukharin. This occurred despite the fact that many of Marx's earlier works on historical materialism, including The German Ideology, remained unpublished until the 1930s.

The substantivist ethnographic approach of economic anthropologist and sociologist Karl Polanyi bears similarities to historical materialism. Polanyi distinguishes between the formal definition of economics as the logic of rational choice between limited resources and a substantive definition of economics as the way humans make their living from their natural and social environment.[13] In The Great Transformation (1944), Polanyi asserts that both the formal and substantive definitions of economics hold true under capitalism, but that the formal definition falls short when analyzing the economic behavior of pre-industrial societies, whose behavior was more often governed by redistribution and reciprocity.[14] While Polanyi was influenced by Marx, he rejected the primacy of economic determinism in shaping the course of history, arguing that rather than being a realm unto itself, an economy is embedded within its contemporary social institutions, such as the state in the case of the market economy.[15]

Perhaps the most notable recent exploration of historical materialism is G. A. Cohen's Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence,[16] which inaugurated the school of Analytical Marxism. Cohen advances a sophisticated technological-determinist interpretation of Marx "in which history is, fundamentally, the growth of human productive power, and forms of society rise and fall according as they enable or impede that growth."[17]

Jürgen Habermas believes historical materialism "needs revision in many respects", especially because it has ignored the significance of communicative action.[18]

Göran Therborn has argued that the method of historical materialism should be applied to historical materialism as an intellectual tradition, and to the history of Marxism itself.[19]

In the early 1980s, Paul Hirst and Barry Hindess elaborated a structural Marxist interpretation of historical materialism.[20]

Regulation theory, especially in the work of Michel Aglietta draws extensively on historical materialism.[21]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, much of Marxist thought was seen as anachronistic. A major effort to "renew" historical materialism comes from historian Ellen Meiksins Wood, who wrote in 1995 that, "There is something off about the assumption that the collapse of Communism represents a terminal crisis for Marxism. One might think, among other things, that in a period of capitalist triumphalism there is more scope than ever for the pursuit of Marxism's principal project, the critique of capitalism."[22]

[T]he kernel of historical materialism was an insistence on the historicity and specificity of capitalism, and denial that its laws were the universal laws of history...this focus on the specificity of capitalism, as a moment with historical origins as well as an end, with a systemic logic specific to it, encourages a truly historical sense lacking in classical political economy and conventional ideas of progress, and this had potentially fruitful implications for the historical study of other modes of production too.[22]

Referencing Marx's Theses on Feuerbach, Wood argued for historical materialism to be understood as "a theoretical foundation for interpreting the world in order to change it."

انظر أيضاً

- Books

- مفاهيم

- Economic determinism

- Formalist–substantivist debate

- Parametric determinism

- Technological determinism

- Technological unemployment

- Theory of historical trajectory

- Comparative

المصادر

- الموسوعة العربية

- فريدريك أنجلس: أصل العائلة و الملكية الخاصة و الدولة

- جوزيف ستالين: المادية التاريخية و الديالكتيكية

|