الحل الشريف

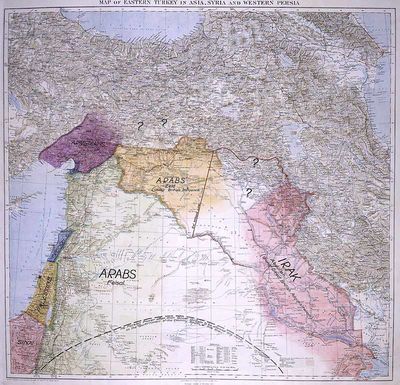

الحل الشريفي Sharifian Solution، وُضع لأول مرة من قبل ت. إ. لورنس عام 1918، كانت خطة لتنصيب ثلاثة من أبناء الشريف الحسين الأربعة كرؤوس دول في البلدان حديثة التأسيس عبر الشرق الأوسط: ابنه الثاني عبد الله حاكماً لبغداد وبلاد الرافدين السفلى، ابنه الثالث فيصل في سوريا، وابنه الرابع زيد في بلاد الرافدين لاعليا. لن يتقلد الشريف نفسه أي سلطة سياسية في هذه الأماكن، وابنه الأول، علي سيخلفه في الحجاز.[2]

بالنظر إلى الحاجة إلى السيطرة على الإنفاق والعوامل الخارجة عن السيطرة البريطانية، بما في ذلك إطاحة فرنسا بفيصل من سوريا في يوليو 1920، ودخول عبد الله عبر الأردن (التي كانت تمثل الجزء الجنوبي من سوريا تحت حكم فيصل) في نوفمبر 1920، كان الحل الشريف في نهاية المطاف مختلفاً، الاسم غير الرسمي للسياسة البريطانية التي وُضعت حيز التنفيذ من قبل وزير الخارجية للمستعمرات ونستون تشرشل بعد مؤتمر القاهرة عام 1921. سيحكم فيصل العراق ويحكم عبد الله عبر الأردن؛ ولم يكن لزيد دوراً، وفي النهاية ثبت أنه من المستحيل إجراء ترتيبات مرضية مع الحسين ومملكة الحجاز.

كانت الفكرة الأساسية هي أن يتم استخدام الضغط في دولمة ما لتأمين طاعة دولة أخرى؛[3] كما تبين، كان الافتراض المتأصل لوحدة الأسرة تصوراً خاطئاً.[4]

لاحقاً استهان صحوة العرب الذي نشره أنطونيوس عام 1938 بمزاعم لورنس في كتابه أعمدة الحكمة السبعة عام 1926 الذي ادعى فيه أن تشرشل "حقق كل التدخل" وأن بريطانيا قد أوفت "بوعودنا نصاً وروحاً".[5]

اغتيل عبد الله عام 1951، لكن لا زال أحفاده يحكمون الأردن حتى الآن. الفرعان الآخران من الأسرة لم ينجمو؛ أطاع ابن سعود بعلي بعدما توقف البريطانيون عن دعم الحسين عام 1924/25، وأُعدم فيصل الثاني، حفيد فيصل في الانقلاب العراقي عام 1958.

التداخل

الفشل في سوريا

كان فيصل أول أبناء الحسين الذين حصلوا على دور رسمي، في ادارة أراضي العدو المحتلة في الشرق، وهي إدارة عسكرية عربية بريطانية مشتركة. دخلت الجيوش العربية والبريطانية دمشق في 1 أكتوبر 1918، وفي 3 أكتوبر 1918 تم تعيين علي رضا الركابي حاكماً عسكرياً لادارة أراضي العدو المحتلة في الشرق.[6][7] دخل فيصل دمشق في 4 أكتوبر وعين الركابي رئيساً لمجلس مديري (أي رئيساً لوزراء) سوريا. كانت تلك الأراضي تتألف من ولاية دمشق العثمانية والجزء الجنوبي من ولاية حلب. أصبحت منطقة معان والعقبة محل نزاع.[8]

أكد فيصل باستمرار أن منطقة سايكس بيكو الزرقاء كانت جزءاً من المنطقة التي وُعد بها حسين في مراسلات مكماهون-حسين.[9] في 15 سبتمبر 1919، توصل لويد جورج وكلمنصو لاتفاقية تنسحب بمقتضاها القوات البريطانية بدءاً من 1 نوفمبر. نتيجة لذلك، أصبحت ادارة أراضي العدو المحتلة في الشرق تحت ادارة عربية منفردة في 26 نوفمبر 1919.[10]

في تلك الأثناء، تم استدعاء فيصل إلى لندن، ووصل إلى هناك في 18 سبتمبر، وتبين له في النهاية أنه سيتعين عليه أن يفعل ما بوسعه مع الفرنسيين.[11] أثناء وجوده في لندن، حصل فيصل على نسخ من جميع مراسلات مكماهون-حسين التي لم يتم إطلاعه عليها بالكامل؛ وفقاً لسيرة سيرته، يعتقد فيصل أنه قد ضلل من قِبل والده وعبد الله في هذا الصدد.[12][13] وصل فيصل باريس في 20 أكتوبر.[14]

في النهاية توصل فيصل كملنصو لاتفاق في 6 يناير 1920، يقضي بأن تسمح فرنسا باستقلال محدود لسوريا حيث يكون فيصل ملكاً شريطة أن تظل سوريا تحت الوصاية الفرنسية، وعلى سوريا أن تقبل الانتداب الفرنسي والسيطرة على سياستها الخارجية.[15]

سيطرت على المشهد السياسي في دمشق ثلاث منظمات، النادي العربي (النادي العربي الذي يتمتع بصلات فلسطينية قوية)، وحزب الاستقلال العربي (حزب الاستقلال العربي المرتبط بجمعية العربية الفتاة) والعهد (رابطة الضباط العراقيين).[16]

بعد عودته إلى دمشق في 16 يناير، أثبت فيصل أنه غير قادراً على إقناع هؤلاء المؤيدين بمزايا ترتيباته مع كليمنصو، وأعلن المؤتمر الوطني السوري في 8 مارس 1920 فيصل ملكاً للمملكة العربية السورية على كامل المنطقة الشرقية من ادارة أراضي العدو المحتلة، وملكاً اسمياً على بقية منطقة سوريا التاريخية (التي تشمل فلسطين). بالاشتراك مع الفرنسيين، رفض اللورد كرزون وطلب من فيصل إثارة قضيته في المجلس الأعلى.[17][18] في 30 مارس التقى كرزون بالسفير الفرنسي ولاحظ أن الدعم الأنگلو فرنسي الشهري البالغة قيمته 100 ألف جنيه استرليني لفيصل لم يتم دفعه منذ نهاية عام 1919 وينبغيعدم دفعه إذا اتبع فيصل "سياسة غير ودية ومستقلة".[19]

في أبريل 1920 منح مؤتمر سان ريمو لفرنسا الانتداب على سوريا؛ وكان الدعوة قد وجهت لفيصل لحضور المؤتمر لكنه لم يذهب، حضر المؤتمر نوري السعيد، رستم حيدر ونجيب شقير بشكل غير رسمي، ووصلوا متأخرين أسبوع تقريباً وظلوا منعزلين عن القرارات الرئيسية للمؤتمر.[20]

في 11 مايو، كتب ميران (الذي خلف كلمنصو في 20 يناير):

...لم يعد باستطاعة الحكومة الفرنسية من الىن فصاعداً الموافقة على الانتهاك اليومي لمبادئ الاتفاقية التي قبل بها الأمير ... لا يمكن لفيصل أن يكون في آن واحد وفي الوقت نفسه ممثل ملك الحجاز، لمطالب عموم العرب وأميراً لسوريا، التي وضعت تحت الانتداب الفرنسي.

حسب فريدمان، في 26 أبريل 1920، فقد أخبر حسين اللبني بأنه صاحب الحق الحصري للتمثيل في مؤتمر السلام، وأنه عين عبد الله ليحل محل فيصل وفي 23 مايو 1920، تلقى لويد جورج برقية مفادها: "في ضوء القرارات المتخذة من قبل المؤتمر السوري، لا يمكن لفيصل أن يتحدث نيابة عن سوريا". [21]

انتهت الجمهورية السورية العربية في 25 يوليو 1920 في أعقاب الحرب الفرنسية السورية ومعركة ميسلون.[22]

الانتدابات، المال والسياسات البريطانية

خلال عام 1920، نوقشت سياسات بريطانيا في الشرق الأوسط بشكل متكرر. كان هناك نواب يعرفون المجال الذي يمنح البرلمان وسائل التشكيك في تلك السياسة. [23] أشار تيموثي پاريس أن هناك العديد من الأمثلة على النقاش البرلماني حول سياسة بريطانيا في فلسطين، ومن أمثلتها ذلك الذي كان يستفسر عن امتثال البريطانيين مع الانتداب.[24][25]

كان البريطانيون عازمون على تأمين العرب، وعلى وجه الخصوص، موافقة حسين على الانتداب، وخاصة الانتداب على فلسطين. لم يصادق حسين على معاهدة ڤرساي ولم يوقع معاهدة سيڤر ولم يقبل بالانتدابات. كان من شأن توقيع حسين أن يهدئ الفصائل البرلمانية التي أشارت مراراً وتكراراً إلى عدم تنفيذ العرب لتعهداتهم. قوض هذا الهيكل الهش أيدي تشرشل فيما يحصل الحل الشريف الذي كان يستند جزئياً على فكرة وجود شبكة من العلاقات الأسرية.[26]

في دوره كوزير للحرب، كان تشرشل ينادي منذ عام 1919 بالانسحاب من أراضي الشرق الأوسط لأنه سيورط بريطانيا "في نفقات هائلة على المؤسسات العسكرية وأعمال التطوير التي تتجاوز بكثير أي إمكانية للعودة" وفي عام 1920 فيما يتعلق بفلسطين أشار إلى أن "الانسحاب مشروع فلسطين هو الأكثر صعوبة وهو بالتأكيد لن يحقق أي ربح من أي نوع".[27]

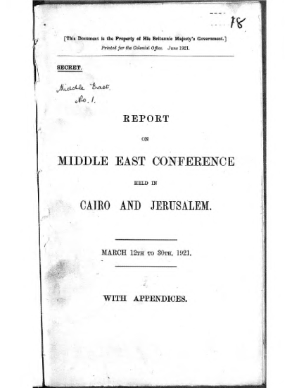

في 14 فبراير 1921، تولى تشرشل منصب في مكتب المستعمرات المكلف بصنع الاقتصادات في الشرق الأوسط. قام بالترتيب لعقد مؤتمر في القاهرة بهدف تحقيق هذه الغاية، وكذلك التوصل إلى تسوية أنگلو-عربية.[28]

القاهرة والقدس

إلى جانب تشرشل ولورنس، ضم مؤتمر القاهرة المندوبون پرسي كوكس وهربرت صمويل بالإضافة إلى گرترود بل والعراقيين، جعفر العسكري، المعروف لدى فيصل، وساسون حسقيل، وزيرا الدفاع والمالية المؤقتين[29] على التوالي في العراق في ذلك الوقت. [30] في 23 مارس، غادر تشرشل إلى القدس وعاد إلى لندن في 2 أبريل.[31]

في سياق تقرير تم تقديمه إلى البرلمان في 14 يونيو 1921 والذي نتائج المؤتمر، قال تشرشل:

نحن نميل بقوة إلى ما يمكن أن أسميه الحل الشريف، سواء في بلاد الرافدين، والتي يحكمها الأمير فيصل، وفي عبر الأردن، حيث يتولى الأمير عبد الله الآن المسؤولية. كما نقدم المساعدة والدعم للملك حسين، شريف مكة، الذي تأثرت دولته وأمواله بشكل كبير بوقف الحج، الذي تهتم به أمة محمد بشكل كبير، والذي نرغب في استئنافه. يجب مراقبة تداعيات هذه السياسة الشريفة على الزعماء العرب الآخرين بعناية.[32]

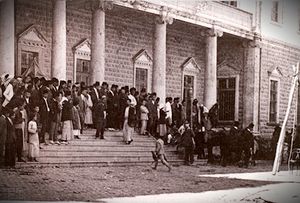

الوقوف الصف الأول: من اليسار: گرترود بل، السير ساسون حسقيل، الفيلد مارشال إدموند اللنبي، جعفر باشا العسكري.

الاجتماعات مع عبد الله

عيّن عبد الله الشريف علي بن الحسين الحارثي مبعوثاً ليذهب إلى الشمال نيابة عنه، وأشار رود إلى أنه بحلول أوائل فبراير 1921 خلص البريطانيون إلى أن "تأثير الشريف قد حل الآن بالكامل محل تأثير الحكومات المحلية والمستشارون البريطانيون في عبر الأردن، [ونبغي] إدراك أنه إذا تقدم عبد الله شمالاً في الربيع، فسيعتبره غالبية السكان حاكماً لتك البلاد".[33] وصل عبد الله عمان في 2 مارس وأرسل عوني عبد الهادي إلا القدس لطمأنة صمويل الذي أصر على أنه لا يمكن استخدام شرق الأردن كقاعدة لمهاجمة سوريا وطلب من عبد الله انتظار وصول تشرشل إلى القاهرة.[34]

ما بين 28 و30 مارس، كان تشرشل قد عقد ثلاث اجتماعات مع عبد الله.[35] اقترح تشرشل تشكيل عبر الأردن كإمارة عربية تحت حكم حاكم عربي، والذي يعترف بالسيطرة البريطانية على إدارته ويكون مسؤولاً أمام المفوض السامي لفلسطين وعبر الأردن. جادل عبد الله بأنه يجب أن يُمنح كامل منطقة الانتداب الفلسطينية المسؤولة أمام المفوض السامي. بدلاً من ذلك دعا إلى الاتحاد مع الأراضي الموعودة لأخيه (العراق). رفض تشرشل كلا المطلبين.[36]

استجابة لتخوف عبد الله من تأسيس مملكة يهودية غرب الأردن، قرر تشرشل أنه لم يكن متوقعاً أن "تدفق المئات والآلاف من اليهود إلى البلاد في وقت قصير للغاية وأن يسيطرون على السكان الحاليين"، ولكنه حتى كان أمراً مستحيل تماماً. "الهجرة اليهودية ستكون عملية بطيئة للغاية وسيتم الحفاظ على حقوق السكان الحاليين من غير اليهود". "لن يتم تضمين عبر الأردن في النظام الإداري الحالي لفلسطين، وبالتالي لن يتم تطبيق الأحكام الصهيونية الخاصة بالولاية. لن يتم جعل اللغة العبرية لغة رسمية في عبر الأردن، ولن يتوقع من الحكومة المحلية أن تقوم بأي تدابير لتعزيز الهجرة والاستعمار اليهودي".

حول السياسة البريطانية في فلسطين، أضاف هربرت صمويل أنه "لا يوجد أي شك في تأسيس حكومة يهودية هناك ... لن يتم أخذ أي أرض من أي عربي، ولا يمكن المساس بالدين الإسلامي بأي شكل من الأشكال".[37]

اقترح الممثلون البريطانيون أنه إذا كان عبد الله قادراً على السيطرة على تصرفات القوميين السوريين المعادية لفرنسا، فسوف يقلل ذلك من معارضة فرنسا لترشيح شقيقه لبلاد الرافدين، وربما يؤدي إلى تعيين عبد الله نفسه أميراً لسوريا في دمشق. في النهاية، وافق عبد الله على وقف تقدمه نحو الفرنسيين وإدارة الأراضي الواقعة شرق نهر الأردن لفترة تجريبية مدتها ستة أشهر يُمنح خلالها إعانة بريطانية قدرها 5000 جنيه إسترليني شهرياً.[38]

عبر الأردن

الإقليم، الذي سيصبح جزءاً من عبر الأردن، تم فصله عن منطقة الانتداب الفرنسي بعد هزيمة الفرنسيين للملك فيصل في يوليو 1920.[39] لبعض الوقت، لم يكن للمنطقة حاكم راسخ ولا قوة احتلال.[40] خلال تلك الفترة أصبحت عبر الأردن منطقة محرمة[41] أو على حد تعبير هربرت صمويل، "..تُركت مهمة سياسياً".[42][43]

في 7 سبتمبر، كان رفيفان المجالي (الكرك) والسلطان العدوان (البلقاء)، اللذان يدعمان البريطانيين، د تلقيا برقيات من حسين يعلمهما أن أحد أبنائه كان متجهاً شمالاً لتنظيم حركة لطرد الفرنسيين من سوريا. وصل عبد الله معان في 21 نوفمبر 1920 مغادراً إياها في 29 فبراير ووصل عمان في 2 مارس 1921.[44]

أسس عبد الله حكومته في 11 أبريل 1921.[45]

العراق

طموحات عبد الله في العراق

في نفس اليوم الذي أًعلن فيه فيصل ملكاً على سوريا، عقد العهد المجلس العراقي (مجلساً من 29 عراقياً في دمشق ضم جعفر العسكري وصهره نوري السعيد)، دعوا فيها إلى استقلال العراق، وتنصيب عبد الله ملكاً وزيداً نائباً له؛ وكذلك اتحاد العراقي مع سوريا في نهاية المطاف.[أ] بدأت الثورة العراقية ضد البريطانيين بعد بضعة أسابيع من نهاية يونيو 1920.[48]

طموحات فيصل في العراق

بعد سقوط المملكة السورية العربية، وصل فيصل عبر حيفا (1 إلى 18 أغسطس) إلى إيطاليا، ووصل إلى ناپولي في 25 أغسطس 1920. في الطريق، أعطى عبد الملك الخطيب، ممثل الحجاز في مصر، فيصل خطاباً من حسين يقول فيه إنه يتعين على فيصل مناقشة السياسة فقط مع الحكومة البريطانية وأن يكون ذلك فقط على أساس مراسلات مكماهون-حسين، مع تأنيبه لفيصل أيضاً "لإعلانه تأسيس مملكة منفصلة وعدم الاكتفاء بالبقاء كممثل لحسين".[49][21] وفقاً لما ذكره مدير المكتب العربي، في حديثه عن المناقشات بين فيصل وعبد الملك، فيما يتعلق بالعراق "... إذا كانت الحكومة البريطانية ترغب في رحيله، فهو مستعد إما أن يكون حاكماً وصياً على عبد الله..."[50][51]

ذهب فيصل إلى سويسرا حيث كان يقضي لويد جورج إجازته، لكن تم إقناعه بعدم فعل ذلك من خلال رسالة من البريطانيين تطلب منه انتظار دعوة إلى إنگلترة، فذهب بدلاً من ذلك إلى بحيرة كومو وبقي هناك للأشهر الثلاثة المقبلة.[52]

في نوفمبر عين حصين فيصل رئيساً لوفد الحجاز في أوروپا، وترك فيصل إنگلترة في 28 نوفمبر.

فيصل في إنگلترة

وصل فيصل إنگلترة في 1 ديسمبر [53] والتقى بالملك جورج في 4 ديسمبر.[54] رداً على المخاوف البريطانية المبكرة، أرسل فيصل في أوائل ديسمبر برقيات إلى حسين يطلب فيها التدخل لدى عبد الله كي لا تفسد مناقشات لندن بتهديدات عبد الله بالعمل ضد الفرنسيين.[55][56]

في 9 ديسمبر، تبعاً لكاتب سيرة فيصل، سجل حيدر في يومياتها "لقد تناولنا الغداء مع لورانس وهوگارث ... يبدو من تصريحات لورنس أن بريطانيا ستعمل في العراق. وسأل [لورنس] الأمير [فيصل] عن آرائه. لا شك في أن [فيصل] كان يريد هذا [الموقف] حتى لو كان من شأنه أن يؤدي إلى الصراع مع عائلته".[57]

بعد حصوله على إذن من حسين في 19 ديسمبر للدخول في مناقشات رسمية، قام فيصل مع حيدر والجنرال جبرائيل حداد،[58] في 23 ديسمبر بلقاء السير جون تيلي، هبرت ينگ وكيناهان كورنواليس. في هذا الاجتماع، أثيرت قضية توقيع حسين على معاهدة سيڤر وFaisal explained that Hussein would not sign until he was sure about Britain's intention to fulfill its promises to him. There were discussions about the McMahon-Hussein correspondence and its meaning and an agreement to set out English and Arabic versions side by side to see if anything might be resolved.[59][60][61]

The next day[62] the English and Arabic texts of were compared. As one official, who was present, put it,[63]

In the Arabic version sent to King Husain this is so translated as to make it appear that Gt Britain is free to act without detriment to France in the whole of the limits mentioned. This passage of course had been our sheet anchor: it enabled us to tell the French that we had reserved their rights, and the Arabs that there were regions in which they would have eventually to come to terms with the French. It is extremely awkward to have this piece of solid ground cut from under our feet. I think that HMG will probably jump at the opportunity of making a sort of amende by sending Feisal to Mesopotamia. [ب]

Paris cites Kedourie[65] to claim that Young's translation was at fault, that "Young, Cornwallis and Storrs all appear to have been mistaken" [66] and Friedman asserts that the Arabic document produced by Faisal was "not authentic", a "fabrication".[67]

In early January, Faisal was given a print, ordered by Young, of the "Summary of Historical Documents from...1914 to the out-break of Revolt of the Sherif of Mecca in June 1916," dated 29 November 1916.[68] Young on 29 November 1920 had written a "Foreign Office Memorandum on possible negotiations with the Hedjaz," addressing the intended content of a treaty,[69] interpreting the Arabic translation to be referring to the Vilayet of Damascus. This was the first time an argument was put forward that the correspondence was intended to exclude Palestine from the Arab area.[61]

On 7 January and into the early hours of 8 January, Cornwallis, acting informally with instructions from Curzon, sounded out Faisal on Iraq. While agreeing in principle to a mandate and not to intrigue against the French, Faisal was equivocal about his candidacy: "I will never put myself forward as a candidate"...Hussein wants "Abdullah to go to Mesopotamia" and "the people would believe I was working for myself and not for my nation." He would go "if HMG rejected Abdullah and asked me to undertake the task and if the people said they wanted me". Cornwallis thought that Faisal wanted to go to Mesopotamia but would not push himself or work against Abdullah.[70][71][72]

On 8 January, Faisal joined Lawrence, Cornwallis, The Hon. William Ormsby-Gore, MP and Walter Guinness MP at Edward Turnour, Earl Winterton's country house for the weekend. Allawi quotes Winterton's memoirs in support of the claim that Faisal agreed after many hours of discussions to become King of Iraq.[73] Paris says that Winterton had been approached by Philip Kerr, Lloyd George's private secretary, with a message that the prime minister "was prepared to offer the crown of Iraq to...Faisal if he will accept it. He will not offer it unless he is sure of the Emir's acceptance." Paris also says that the meeting and its results were kept secret.[74]

On 10 January, Faisal met with Lawrence, Ormsby Gore and Guinness. Allawi says that upcoming changes in the department responsible for British Middle Eastern policy were discussed along with the situation in the Hejaz. Faisal continued to demur as regards Iraq, preferring that Britain should put him forward. Lawrence later reported to Churchill on the meeting, but could not yet confirm that Faisal would accept the nomination for Iraq if the British government made him a formal offer.[73]

Faisal and Haddad met Curzon on 13 January 1921. Faisal was concerned about ibn Saud and sought to clarify the British position as the India Office appeared supportive of him. Curzon thought that Hussein threatened his own security by refusing to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Faisal requested arms for the Hejaz and reinstatement of the subsidy but Curzon declined.[75]

Lawrence, in a letter to Churchill on 17 January 1921, wrote that Faisal "had agreed to abandon all claims of his father to Palestine" in return for Arab sovereignty in Iraq, Trans-Jordan and Syria. Friedman refers to this letter as being from Lawrence to Marsh (Churchill's private secretary), states that the date of 17 January is erroneous ("a slip of the pen, or a misprint") and claims that the most likely date is 17 February. Friedman as well refers to an undated ("presumably 17 February") letter from Lawrence to Churchill that does not contain this statement.[76] Paris references only the Marsh letter and while claiming the evidence is unclear, suggests that the letter may have described a meeting that took place shortly after 8 January at Earl Winterton's country house.[77]

On 20 January, Faisal, Haddad, Haidar, Young, Cornwallis and Ronald Lindsay met. Faisal's biographer says that this meeting led to a misunderstanding that would later be used against Faisal as Churchill later claimed in parliament that Faisal had acknowledged that the territory of Palestine was specifically excluded from the promises of support for an independent Arab Kingdom. Allawi says that the minutes of the meeting show only that Faisal accepted that this could be the British government interpretation of the exchanges without necessarily agreeing with them.[78]In parliament, Churchill in 1922 confirmed this, "...a conversation held in the Foreign Office on the 20th January, 1921, more than five years after the conclusion of the correspondence on which the claim was based. On that occasion the point of view of His Majesty's Government was explained to the Emir, who expressed himself as prepared to accept the statement that it had been the intention of His Majesty's Government to exclude Palestine."[79]

Rudd says that, in regards to Iraq, Lindsay commented in his record of the meeting that "If he is a member of the Sherifian family we should welcome him. If it is Abdullah well and good. If Feisal—perhaps better."[80]

The 7 December draft of the Mandate for Palestine was published in The Times on 3 February 1921 and according to Paris, Faisal made a formal protest to Curzon on 6 January, the gist of which was also published in the Times on 9 February.[81] According to historian Susan Pedersen, Faisal also on 16 February, filed a petition to the League of Nations on behalf of his father, that the situation violated wartime pledges as well as Article 22 of the Covenant. The petition was ruled "not receivable" on the "dubious" grounds that a peace treaty had not been signed with Turkey.[82]

On 16 February Faisal met Lawrence and Allawi quotes Lawrence as saying "I explained to him that I had just accepted an appointment in the Middle Eastern Department of the Colonial Office...I then spoke of what might happen in the near future, mentioning a possible conference in Egypt...in which the politics, constitution and finances of the Arabic areas of Western Asia would come in discussion...These were all of direct interest to his race, and especially to his family, and I thought present signs justified his being reasonably hopeful of a settlement satisfactory to all parties."[83] Karsh gives a similar report and while reporting on the Marsh letter, does not connect it to this meeting.[84] (This meeting is determined by Friedman to be the meeting subject of the undated letter from Lawrence to Marsh [85]).

On 22 February Faisal met Churchill, with Lawrence intrpreting.As recorded by Lawrence, Faisal's acceptance of the Mandate and a promise not to intrigue against the French were not explicitly agreed upon. Faisal askec Churchill about the mandate and while he considered the Mandate as important Faisal did express doubts about what a Mandate would entail. The meeting concluded with Churchill telling Faisal that 'things might be arranged' by 25 March and that Faisal should remain in London 'in case his advice or agreement was needed'.[86]

On 10 March Faisal's submitted the Conference of London—Memorandum Submitted to the Conference of Allied Powers at the House of Commons.[87] Faisal had written to Lloyd George on 21 February to reiterate Hussein's position on Sèvres and to ask that a Hejazi delegation be allowed to attend. Lloyd George tabled the letter at the meeting but the French objected and only finally agreed to receive a submission form Haddad on Faisal's behalf.[88]

The Cairo conference having opened on 12 March and deliberated Faisal's candidature for Iraq, on March 22 Lloyd George told Churchill that the Cabinet were "..much impressed by collective force of your recommendations ... and it was thought that order of events should be as follows:"

Sir P. Cox should return with as little delay as possible to Mesopotamia, and should set going the machinery which may result in acceptance of Feisal's candidature and invitation to him to accept position of ruler of Irak. In the meantime, no announcement or communication to the French should be made. Feisal, however, will be told privately that there is no longer any need for him to remain in England, and that he should return without delay to Mecca to consult his father, who appears from our latest reports to be in a more than usually unamiable frame of mind. Feisal also will be told that if, with his father's and brother's consent, he becomes a candidate for Mesopotamia and is accepted by people of that country, we shall welcome their choice, subject, of course, to the double condition that he is prepared to accept terms of mandate as laid before League of Nations, and that he will not utilise his position to intrigue against or attack the French ... If above conditions are fulfilled, Feisal would then from Mecca make known at the right moment his desire to offer himself as candidate, and should make his appeal to the Mesopotamian people. At this stage we could, if necessary, communicate with the French, who, whatever their suspicions or annoyance, would have no ground for protest against a course of action in strict accordance with our previous declarations.[89]

Lawrence cabled Faisal on 23 March: "Things have gone exactly as hoped. Please start for Mecca at once by the quickest possible route... I will meet you on the way and explain the details."[90] Faisal left England at the beginning of April.

العودة للوطن

At Port Said on 11 April 1921, Faisal met Lawrence to discuss the Cairo conference and way ahead. Of the meeting, Lawrence wrote to Churchill that Faisal promised to do his part and guaranteed not to attack or intrigue against the French. Faisal once again expressed reservations about the Mandate.[91]

Faisal reached Jeddah on 25 April and after consultations with Hussein in Mecca and making preparations for his upcoming arrival in Iraq, departed on 12 June for Basra. With him were Iraqis who had taken refuge in the Hejaz after the 1920 rebellion and were now returning as part of the amnesty that had been declared by the British authorities in Iraq along with his own close group of advisers, including Haidar and Tahsin Qadri. Cornwallis, his newly appointed adviser was also there.[92]

ارتقاء فيصل السلطة

Faisal arrived in Basra on 23 June 1921, his first time ever in Iraq, and was to be crowned King just two months later on 23 August 1921.[75]

الحسين والحجاز

التحول ونهاية الدعم

Having received £6.5m between 1916 and April 1919, in May 1919 the subsidy was reduced to £100k monthly (from £200k), dropped to £75K from October, £50k in November, £25k in December until February 1920 after which no more payments were made. After Churchill took over the Colonial Office, he was supportive of the payment of subsidies and argued that given the projected financial savings in Iraq, an amount of £100k was not exceptional and even, in view of the Sherifian plan, that Hussein ought to receive a larger amount than Ibn Saud. This was an issue that the Cabinet decided, at the same time as limiting any subsidy to £60k and the amount be the same as that for Ibn Saud, needed input from the Foreign Office and Curzon wanted Hussein's signature on the peace treaties.

رفض التوقيع على المعاهدات

In 1919, King Hussein refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. In August 1920, five days after the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, Curzon asked Cairo to procure Hussein's signature to both treaties and agreed to make a payment of £30,000 conditional on signature. Hussein declined and in February 1921, stated that he could not be expected to "affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners."[93]

In July 1921, Lawrence was assigned to the Foreign Office for the purpose of obtaining a treaty arrangement with Hussein as well as the King's signature to Versailles and Sèvres, a £60,000 annual subsidy being proposed; achieving this, which would include the so far denied recognition of the mandates, would constitute the completion of the Sherifian triangle but this attempt also failed.[94] During 1923, the British made one further attempt to settle outstanding issues with Hussein and once again, the attempt foundered, Hussein continued in his refusal to recognize any of the Mandates that he perceived as being his domain. Hussein went to Amman in January 1924 and had further discussions with Samuel and Clayton. In March 1924, following Hussein's self proclamation as Caliph and having briefly considered the possibility of removing the offending article from the treaty, the government suspended any further negotiations.

The British and the pilgrimage

The importance of Mecca to the Muslim world (at the time, Britain effectively ruled a Muslim empire) and to Britain itself as a potential center of rebellion against the Ottoman led to enhanced attention based on the idea that a successful hajj would not only enhance Hussein's standing but indirectly, that of Britain as well.[95]

المطالبة بالخلافة 1924

في 7 مارس 1924، بعد أربعة أيام من إلغاء الخلافة العثمانية, Hussein proclaimed himself Caliph of all Muslims.[96] However, Hussein's reputation in the Muslim world had been damaged by his alliance with Britain, his betrayal of the Ottomans and the division of the ex-Ottoman Arab region into numerous countries; as a result his proclamation attracted more criticism than support in populous Muslim countries like Egypt and India.[97]

العلاقات مع نجد

Nearing the end of 1923, the Hejaz, Iraq and Transjordan all had frontier issues with Najd. The Kuwait conference commenced in November 1923 and continued off and on to May 1924. Hussein initially declined to attend other than under conditions unacceptable to Ibn Saud; the refusal of the latter to send his son, after Hussein had finally agreed to be represented by his own son Zeid, ended the conference.[86]

التنازل عن العرش

After local pressure, Hussein abdicated on 4 October 1924, leaving Jeddah for Aqaba on 14 October. Ali took the throne and also abdicated on 19 December 1925, leaving to join Faisal in Iraq, ending Hashemite rule in the Hejaz.[98]

شجرة العائلة الشريفة

العلاقات بين أفراد العائلة:[99]

شريف مكة نوفمبر 1908 – 3 أكتوبر 1924 ملك الحجاز أكتوبر 1916 – 3 أكتوبر 1924 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ملك الحجاز 3 أكتوبر 1924 – 19 ديسمبر 1925 (الملكية هزمها الفتح السعودي) | أمير (ولاحقاً ملك) الأردن 11 April 1921 – 20 July 1951 | ملك سوريا 8 مارس 1920 – 24 يوليو 1920 ملك العراق 23 أغسطس 1921 – 8 سبتمبر 1933 | زيد (pretender to Iraq) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| عبد الإله (الوصي على عرش العراق) | ملك الأردن 20 يوليو 1951 – 11 أغسطس 1952 | ملك العراق 8 سبتمبر 1933 – 4 أبريل 1939 | رعد (pretender to Iraq) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ملك الأردن 11 August 1952 – 7 February 1999 | ملك العراق 4 أبريل 1939 – 14 يوليو 1958 (الملكية أطاح بها انقلاب | زيد | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ملك الأردن 7 فبراير 1999 – الآن | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحسين (ولي عهد الأردن) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

الهوامش

الحواشي

- ^ Abdullah's reaction to this is not known, according to author Ian Rutledge[46] في إشارة رود إلى محادثة بين عبد الله وڤيكري في 1 مارس: "... إنه يود بالتأكيد أن يكون أمير العراق إذا ضمن الدعم والمساعدة البريطانية لمدة 20 عاماً على الأقل. ولن يقبل أي منصب في أي بلد لم يكن لبريطانيا العظمى انتداباً عليه...".[47]

- ^ In his Setting the Desert on Fire published 2 years earlier, Barr had in addition described how after being missing for nearly fifteen years, copies of the Arabic versions of the two most significant letters were found in a clear-out of Ronald Storrs's office in Cairo. "This careless translation completely changes the meaning of the reservation, or at any rate makes the meaning exceedingly ambiguous,"the Lord Chancellor admitted, in a secret legal opinion on the strength of the Arab claim circulated to the cabinet on 23 January 1939.[64]

المصادر

- ^ "BBC NEWS - UK - Lawrence's Mid-East map on show".

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene L. (2016). "The Emergence of the Middle East into the Modern State System". In Fawcett, Louise (ed.). International relations of the Middle east. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-870874-2.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 246.

- ^ Arab Awakening. Taylor & Francis. 19 December 2013. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-317-84769-4.

- ^ William E. Watson (2003). Tricolor and Crescent: France and the Islamic World. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-275-97470-1.

- ^ Eliezer Tauber (5 March 2014). The Arab Movements in World War I. Routledge. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-135-19978-4.

- ^ Troeller, Gary (23 October 2013). The Birth of Saudi Arabia: Britain and the Rise of the House of Sa'ud. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-16198-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Zamir, Meir (6 December 2006). "Faisal and the Lebanese question, 1918–20". Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (3): 404. doi:10.1080/00263209108700868.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Lieshout, Robert H. (2016). Britain and the Arab Middle East: World War I and its Aftermath. I.B.Tauris. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-78453-583-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Allawi 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Elie Kedouri (8 April 2014). In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and its Interpretations 1914-1939. Routledge. pp. 229–. ISBN 978-1-135-30842-1.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 253.

- ^ Ayse Tekdal Fildis. "The Troubles in Syria: Spawned by French Divide and Rule". Middle East Policy Council. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Philips S. Khoury, Syria and the French Mandate; The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920-1945 Middle East Studies I. B. Tauris, 1987, p=442

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 269.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 586.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 278.

- ^ أ ب Friedman 2017, p. 272.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 290.

- ^ Bennett 1995, p. 104.

- ^ Hansard, [1]: HL Deb 15 June 1921 vol 45 cc559-63

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Michael J. Cohen (13 September 2013). Churchill and the Jews, 1900-1948. Taylor & Francis. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-1-135-31913-7.

- ^ Bennett 1995, p. 111.

- ^ Reeva Spector Simon; Michael Menachem Laskier; Sara Reguer (30 April 2003). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. Columbia University Press. pp. 353–. ISBN 978-0-231-50759-2.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 360.

- ^ Rudd 1993.

- ^ Middle East, HC Deb 14 June 1921 vol 143 cc265-334

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 309.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 312.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 305.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 307.

- ^ Report on Middle East Conference held in Cairo and Jerusalem, March 12th to 30th, 1921, Appendix 19, p. 109-111. British Colonial Office, June 1921 (CO 935/1/1)

- ^ Joab B. Eilon; Yoav Alon (30 March 2007). The Making of Jordan: Tribes, Colonialism and the Modern State. I.B.Tauris. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-84511-138-0.

- ^ Macmunn & Falls 1930, p. 609.

- ^ Dann, U. (1969). The Beginnings of the Arab Legion. Middle Eastern Studies,5(3), 181-191. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4282290 "...the interregnum between Faysal's departure from Syria and 'Abdallah's installation at 'Amman."

- ^ Norman Bentwich, England in Palestine, p51, "The High Commissioner had ... only been in office a few days when Emir Faisal ... had to flee his kingdom" and "The departure of Faisal and the breaking up of the Emirate of Syria left the territory on the east side of Jordan in a puzzling state of detachment. It was for a time no-man's-land. In the Ottoman regime the territory was attached to the Vilayet of Damascus; under the Military Administration it had been treated a part of the eastern occupied territory which was governed from Damascus; but it was now impossible that that subordination should continue, and its natural attachment was with Palestine. The territory was, indeed, included in the Mandated territory of Palestine, but difficult issues were involved as to application there of the clauses of the Mandate concerning the Jewish National Home. The undertakings given to the Arabs as to the autonomous Arab region included the territory. Lastly, His Majesty's Government were unwilling to embark on any definite commitment, and vetoed any entry into the territory by the troops. The Arabs were therefore left to work out their destiny."

- ^ Pipes, Daniel (26 March 1992). Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-19-536304-3.

- ^ Edward W. Said; Christopher Hitchens (2001). Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question. Verso. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-1-85984-340-6.

- ^ Vatikiotis, P.J. (18 May 2017). Politics and the Military in Jordan: A Study of the Arab Legion, 1921–1957. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-78303-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Gökhan Bacik (2008). Hybrid sovereignty in the Arab Middle East: the cases of Kuwait, Jordan, and Iraq. Macmillan. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-230-60040-9. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ Ian Rutledge (1 June 2015). Enemy on the Euphrates: The Battle for Iraq, 1914 - 1921. Saqi. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-86356-767-4.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 257.

- ^ Charles Tripp (27 May 2002). A History of Iraq. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-52900-6.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 301.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 122.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 312.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 304.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 309.

- ^ Paris & 2004 p0119.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 318.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 316.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 316.

- ^ Barry Rubin; Wolfgang G. Schwanitz (25 February 2014). Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Yale University Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-300-14090-3.

- ^ Younan Labib Rizk (21 August 2009). Britain and Arab Unity: A Documentary History from the Treaty of Versailles to the End of World War II. I.B.Tauris. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-85771-103-8.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 319.

- ^ أ ب Friedman 2017, p. 297.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 298.

- ^ Barr, James (2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-84983-903-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ James Barr (7 November 2011). Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence and Britain's Secret War in Arabia, 1916-18. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 250–. ISBN 978-1-4088-2789-5.

- ^ Elie Kedouri (8 April 2014). In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth: The McMahon-Husayn Correspondence and its Interpretations 1914-1939. Routledge. pp. 237–41. ISBN 978-1-135-30842-1.

- ^ Paris 2003.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 299.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 312.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 121.

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 317.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 321.

- ^ أ ب Allawi 2014, p. 322.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 128.

- ^ أ ب Allawi 2014.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 277.

- ^ Paris 2003, p. 129.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 323.

- ^ Hansard, "PLEDGES TO ARABS.": HC Deb 11 July 1922 vol 156 cc1032–5

- ^ Rudd 1993, p. 318.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 130.

- ^ The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford University Press. 29 April 2015. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-19-022639-8.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 326.

- ^ Efraim Karsh; Inari Karsh (2001). Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923. Harvard University Press. pp. 286–. ISBN 978-0-674-00541-9.

- ^ Friedman 2017, p. 307.

- ^ أ ب Paris 2004.

- ^ "Memorandum Submitted to the Conference of Allied Powers at the House of Commons". Unispal. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 329.

- ^ Efraim Karsh; Inari Karsh (June 2009). Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923. Harvard University Press. pp. 392–. ISBN 978-0-674-03934-6.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Allawi 2004, p. 333.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 336.

- ^ Mousa, Suleiman (1978). "A Matter of Principle: King Hussein of the Hejaz and the Arabs of Palestine". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 9 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000052.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Paris 2004, p. 252.

- ^ John Slight (12 October 2015). The British Empire and the Hajj. Harvard University Press. pp. 176–. ISBN 978-0-674-91582-4.

- ^ Teitelbaum, Joshua (2000). ""Taking Back" the Caliphate: Sharīf Ḥusayn Ibn ʿAlī, Mustafa Kemal and the Ottoman Caliphate". Die Welt des Islams. 40 (3): 412–424. doi:10.1163/1570060001505343. JSTOR 1571258.

- ^ Al-Rasheed, Madawi; Kersten, Carool; Shterin, Marat (12 November 2012). Demystifying the Caliphate: Historical Memory and Contemporary Contexts. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-0-19-025712-5.

- ^ Paris 2004, p. 344.

- ^ "Welcome to the Office of King Hussein I dedicated to the father of Modern Jordan". The Royal Hashemite Court. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

المراجع

- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-300-19936-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bennett, G. (9 August 1995). British Foreign Policy during the Curzon Period, 1919–24. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-37735-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedman, Isaiah (8 September 2017). British Pan-Arab Policy, 1915–1922. Taylor & Francis. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-351-53064-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paris, Timothy J. (23 November 2004). Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule: The Sherifian Solution. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-77191-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rudd, Jeffery A. (1993). Abdallah bin al-Husayn: The Making of an Arab Political Leader, 1908–1921 (PDF) (PhD). SOAS Research Online. pp. 45–46. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)