قصف الجزائر (1783)

| قصف الجزائر (1783) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من الحرب الإسپانية-الجزائرية 1775-85 | |||||||

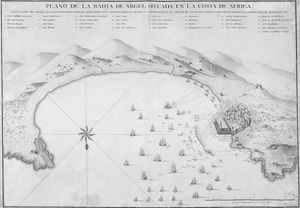

خريطة قصف الجزائر 1783 رسم أنطونيو بارسلو. | |||||||

| |||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| 4 ships of line, 4 فرقاطات، 68 سفينة أخرى[4] | 2 demi-galleys, 2 xebecs, 6 gunboats, 1 فلوكة[1] | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| 26 killed, 14 wounded[5] | 1 gunboat[1] | ||||||

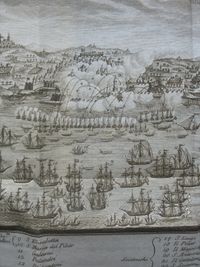

قصف الجزائر في أغسطس 1783، كانت محاولة فاشلة شنتها إسپانيا لوضع نهاية لقرصنة الجزائريين على السفن الإسپانية. قام أسطول إسپاني على متنه 70 بحار تحت قيادة الأميرال أنطونيو بارسلو بتفجير المدينة ثمان مرات ما بين 4 و8 أغسطس، لكن تلك الهجمات ألحقت أضرار قليلة بالجيش الجزائري. كان القتال ضعيفاً على كلا الجانبين الإسپاني والجزائري، بسبب سوء الأحوال الجوية، مما دفع الجنود إلى الإنسحاب. وقضت المحكمة الإسپانية على تلك التجريدة بالفشل، ووصفت بأنها "مهرجان ألعاب نارية باهظ التكلفة ومطوَّل لم يسلي العرب ولم ينشغل به إلا من دفع تكلفته.".[6]

خلفية

كانت قرصنة البربر وتجارة العبيد واختطاف الاوروبيين واستعبادهم، هي السبب المعلن لما تعرضت له مدن الجزائر ووهران وطنجة والمرسى الكبير وقرطاج وطرابلس والدار البيضاء، في الفترة من 1750-1830 من قصف مدفعي مكثف، نحو 5-10 مرات لكل مدينة، من أساطيل بريطانيا وهولندا واسبانيا والدنمارك والسويد والولايات المتحدة وإيطاليا وفرنسا.

تزايدت القرصنة الجزائرية ضد السفن الاسبانية إثر غزو الجزائر الكارثي في 1775.[2] حاولت اسبانيا التوصل لاتفاقية سلام مع الدولة العثمانية بهدف تأمين تجارتها في البحر المتوسط. وأُرسِل دون خوان ده بوليني إلى الآستانة في 1782 ونجح في الحصول على اتفاقية صداقة وتجارة من السلطان عبد الحميد الأول.[2] The Regency, nevertheless, denied to accept the treaty. The Dey, influenced by several of his officers, the fasnachi, the treasurer, the focha, the Codgia of cavalry and the Aga of infantry, opted for war ignoring the recommendations of his naval officers.[3] The Spanish chief minister, the Count of Floridablanca, tried then to bribe the Dey with gold to open negotiations for peace, but obtaining no result.[3]

الملك كارلوس الثالث، feeling the national pride of Spain offended by the Algerines, resolved to punish them bombarding their town.[7] Rear admiral Antonio Barceló was the man appointed to carry out the attack. Though he was by far the most capable naval officer of Spain and one of the few who had risen through the ranks by merits of war, Barceló's designation was coldly received both by the Spanish court and military.[8] وكان أميرال المؤخرة عجوزاً أمياً من أصول متواضعة، مما جعله، بالاضافة لانتصاراته البحرية، موضع حسد معظم كبار الضباط الاسبان.[8]

القصف

أبحر بارسلو من كرتاخينا في 2 يوليو على رأس 4 ships of line, 4 frigates and 68 small vassels, including gunboats and bomb vessels. The Algerines had to oppose them no more than 2 demi-gallies of 5 guns each, a felucca of 6, two xebecs of 4 guns each, and 6 gunboats carrying a 12 and a 24 pounder.[1] On 29 July the Spanish fleet came in sight of the town and two days later Barceló formed his line of battle and made the necessary dispositions for the attack. The bomb-ketches and gunboats, supported by xebecs and other vessels, composed the van, the whole being covered by the ships of line and frigates.[9]

The cannonade and bombardment were commenced at half-past two o'clock, and were continued without intermission till sunset.[9] The attack was renewed on the following, and on every succeeding day util the 9th, when it was resolved at a council of war, for sufficient reasons, to return immediately to Spain.[9] In the course of these attacks 3732 shells and 3833 shot were discharged by the Spaniards, and were returned by the Algerines with 399 shells and 11,284 shot. This vast expenditure of ammunition produced no correspondent effect on either side: the town was repeatedly set on fire, but the flames were soon subdued.[9]

مثال جبل طارق اتبعته الحامية في استخدام red-hot balls, but they did not produce a similar effect. The Algerines made several bold sallies with their small vessels, but were constantly repulsed by the superiority of fire from the fleet.[9] While de Dey had refuged at his citadel, the weight of the defense was sustained by an improvised militia composed moslty of teenagers. 25 Algerine heavy guns purchased at Denmark blown up during the battle due to misuse or because its poor conditions.[10] In addition, 562 buildings were destroyed or damaged by the bombardment, an insignificant figure given that Algiers consisted of 5,000 buildings and that the whole town was exposed to the Spanish fire.[10] Otherwise, only a gunboat was lost by the defenders. The Spanish casualties were also minimum: 26 killed and 14 wounded.[5]

التبعات

According to the official version released by the Spanish government, the withdrawal was due to bad weather, an excuse not credible, given that the weather conditions in the Mediterranean were favorable in summer.[6] Among the measures used to present the bombing as a success, the most significant was that of numerous promotions among the participants.[6] The Spanish 'victory' was sung by numerous poems, most of them exaggerated and of bad taste, but in fact nothing had been achieved.[3] Two months later five Algerian privateers captured two Spanish merchant vessels near Palamós as a gesture of defiance, and a new, far bigger expedition had to be assembled to attack Algiers again.[5]

هوامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث Pinkerton 1809, p. 461.

- ^ أ ب ت Sánchez Doncel 1991, p. 274.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Conrotte/Martín Corrales 2006, p. 165.

- ^ Fernández Duro 1972, p. 345.

- ^ أ ب ت Fernández Duro 1972, p. 346.

- ^ أ ب ت Conrotte/Martín Corrales 2006, p. 164.

- ^ Conrotte/Martín Corrales 2006, p. 160.

- ^ أ ب Conrotte/Martín Corrales 2006, p. 162.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Cust 1859, p. 14.

- ^ أ ب Conrotte/Martín Corrales 2006, p. 163.

المصادر

- Conrotte, Manuel/Corrales, Eloy Martín (2006). España y los países musulmanes durante el ministerio de Floridablanca. Spain: Editorial Renacimiento. ISBN 8496133575.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)Español: قالب:Description/i18n - Cust, Edward (1859). España Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century, compiled from the most authentic histories of the period: 1783-1795. London: Mitchell's Military Library.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1902). Armada española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y de León. Vol VII. Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)Español: قالب:Description/i18n - Pinkerton, John (1809). A general collection of the best and most interesting voyages and travels in all parts of the world: many of which are now first translated into English ; digested on a new plan. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sánchez Doncel, Gregorio (1991). Presencia de España en Orán (1509-1792). Toledo: I.T. San Ildefonso. ISBN 9788460076148.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)Español: قالب:Description/i18n