السيمفونية الخامسة (بيتهوڤن)

| سيمفونية على سلم دو الصغير | |

|---|---|

| الخامسة | |

| تأليف موسيقي لودڤيگ ڤان بيتهوڤن | |

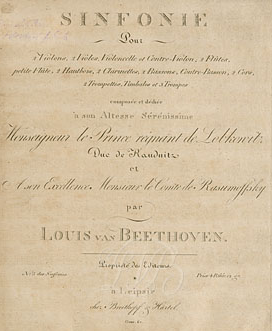

غلاف السيفمونية، مع إهداء للأمير يوسف فرانز فون لوبكوڤتس والكونت رازوموڤسكي | |

| المفتاح | دو الصغير |

| ر. | Op. 67 |

| الشكل | سيمفونية |

| Composed | 1804–1808 |

| Dedication |

|

| المدة | حوالي 30–40 دقيقة |

| الحركات | أربعة |

| Scoring | الأوركسترا |

| Premiere | |

| التاريخ | 22 ديسمبر 1808 |

| الموقع | مسرح آن در ڤين، ڤيينا |

| المايسترو | لودڤيگ ڤان بيتهوڤن |

السيمفونية الخامسةوعنوانها ضربات القدر، في سلم دو الصغير، كتبها لودڤيگ ڤان بيتهوڤن، بين عامي 1804 و1808. وتعتبر من أشهر المؤلفات في الموسيقى الكلاسيكية ومن أكثر السيمفونيات عزفاً،[1] كما تعتبر من الأركان الرئيسية في الموسيقى الغربية. عُزفت لأول مرة في مسرح آن دير ڤاين بڤيينا عام 1808، وبعد فترة وجيزة حقق العمل سمعته الرائعة. وصف إ. ت. أ. هوفمان السيمفونية بأنها "واحدة من أهم الأعمال في ذلك الوقت". كما هو معتاد في السيمفونيات أثناء الانتقال بين الكلاسيكية والرومانسية، فإن السيمفونية الخامسة لبيتهوفن تتكون من أربع حركات موسيقية.

وتبدأ بموتيفة مميزة من أربع نوتات "قصير-قصير-قصير-طويل":

السيمفونية، والموتيفة الافتتاحية ذات الأربع نوتات على وجه الخصوص، معروفان في جميع أنحاء العالم، مع ظهور الموتيفة بشكل متكرر في الثقافة الشعبية، من إصدارات الديسكو إلى أغلفة الروك آند رول، لاستخدامات في السينما والتلفزيون.

مثل سيمفونيتي بيتهوڤن إرويكا (البطولية) و پاستورال (الريفية)، فإن السيمفونية الخامسة أُعطِيَت اسماً صريحاً إلى جانب الترقيم، على الرغم من أن ذلك من يكن من لدن بيتهوفن نفسه. وقد شاعت تحت اسم "Schicksals-Sinfonie" (سيمفونية القدر)، وثيمة الخمس خطوط الشهيرة سُميت "Schicksals-Motiv" (موتيفة القدر). ويُستخدم هذا الاسم أيضاً في الترجمات.

التاريخ

خلفية

كان بيتهوڤن بطبيعة حاله إنسان متشائم، وقد زاد من إنطوائيته وعزلته وعدوانيته، ما لاقاه في طفولته من فقر وحرمان، مما شكل عنده نوع من النظرة السوداء لحياته. وفي مرحلة من مراحل حياته، كان بيتهوڤن يعاني من ضائقة مالية شديدة، وكان يستأجر غرفة أعلى منزل رجل يؤجرها له شهرياً، ويسكن هو في الطابق السفلي لهذا المنزل مع عائلته.

في هذه الأثناء تأخر بيتهوڤن في دفع الإيجار عدة شهور، وبعد عدة مرات طالبه فيها صاحب المنزل بالإيجار، بدأ بيتهوڤن يتهرب من هذا الرجل، فينتظر خروجه إلى عمله في الصباح حتى يخرج بيتهوڤن، كما يترصد غفلته أو إبتعاده عن فناء منزله - الذي لابد لبيتهوڤن أن يستخدمه للصعود على السلالم إلى غرفته - حتى يدخل إلى غرفته، بحيث لو طرق الرجل صاحب المنزل الباب على بيتهوڤن لا يعلم أنه داخل الغرفة أو بالداخل، فحتى لما كان بيتهوڤن داخل غرفته - التي بالمناسبة لم تكن تحتوى إلا على فراش متواضع وبيانو!! - ما كان يرد على أي من يطرق عليه الباب تحسباً أن يكون صاحب البيت جاء ليأخذ الإيجار المتأخر.

وفي يوم من الأيام بينما كان بيتهوڤن عائداً من الخارج، وعندما وجد فناء المنزل خالي، تقدم ليصعد إلى السلم، وعند منتصف السلالم خرج صاحب اليت وشاهد بيتهوڤن فأخذ ينادي عليه، فما كان من بيتهوڤن إلا أن قفز على السلالم حتى باب غرفته ودخل وأغلقها خلفه وهو يشعر بخوف شديد، فقد وجده صاحب المنزل والآن لا مناص من الدفع أو الطرد خارج الغرفة وتسليمه للشرطة! وبالفعل فقد صعد صاحب المنزل وراؤه، وهو متأكد تماماً أن بيتهوڤن في الداخل، وأخذ يطرق الباب بعنف منادياً على بيتهوڤن ومهدداً إياه. فبالفعل لقد كان هذا الرجل يطرق الباب على بيتهوڤن بنفس الطريقة، 4 خبطات، ولكن بمتهى العنف والقوة!!! هنا فجأة وبيتهوڤن يستمع إلى كل هذه الطرقات قفز إلى البيانو الموجود في وسط الغرفة وأخذ يعزف مع الطرقات كلما سمع دفعة من الطرقات (4 خبطات)، أتبعها بأربع نغمات على البيانو وتوقف ثم أربعة أخرى ثم توقف وهكذا لو سمعتم الحركة الأولى لوجدتموها عبارة عن 4 دقات متتالية ثم 4 أخرى، ثم 4 أخرى تتابع بشكل أسرع وهكذا، وألف بيتهوڤن الحركة الأولى كلها منذ بدايتها إلى نهايتها معتمداً على أربع دقات تتابع وتتنوع بين آلات الأوركسترا كلها.[2]

أما عن تحليل الحركة الأولى المميزة لهذه السيمفونية، أن بيتهوڤن تخيل أن القدر - ممثل هنا في صاحب المنزل - قد هجم عليه بمنتهى القوة، وأن القدر تتوالى ضرباته على بيتهوڤن لتجعل كل أوقاته تعيسة، وهي ضربات تتراوح ما بين ضربات قوية وضربات ضعيفة وستلاحظونها في قوة الصوت أو ضعفه عند عزف الأربع دقات كل مرة.

وبطبيعة الحال لا توجد حياة سوداء على طول الخط، لذا فإن بيتهوڤن يعترف بهذا للأمانة النفسية لديه، ويأتي ببعض الألحان المسترسلة الجميلة في أوضاع مختلفة من هذه الحركة، إلا أنها مثل فترات حياته - كما هو متصور - هي قليلة، لا تلبث إلا وتهاجمها ضربات القدر مرة أخرى، وتلاحظونها في هذا العمل تأتي على هيئة ضربات صوتها خفيض وتأتي مصاحبة للألحان المسترسلة وتزداد قوة وعنفاً ما تلبث أن تقضي تماماً على هذه الألحان بالضربات القوية ... وهكذا ضربات تتوالى حتى نهاية الحركة الأولى من هذه السيمفونية الرائعة التي سُميت ضربات القدر.

التأليف

كان بيتهوڤن مشغولاً أثناء كتابتها بعدة أعمال اخرى مثل أوبرا فيديليو والكونشرتو رقم 4 للبيانو كعادة بيتهوڤن فى التأليف الموسيقى.

لمدة خمس سنوات أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية كان هذا اللحن الأساسي هو أشارة الحرية للشعوب المحتلة تحت أقدام النازية لأنه لحن فيه رجوله وقوة فهو بناء موسيقى لا عوج فيه وهو جوهرة فريدة الفها الرجل فى عنفوان عبقريته فهى ذات قوة متدفقة كأنها بركان هائج وغضبة فنان حيال القدر الواقف بالباب يضرب ضربات متلاحقة، وقد قال ذلك بيتهوڤن فعلاً لصديقة شندلر وهو يفسر اللحن الأساسي الأول فى السيمفونية وهذا اللحن الأساسى الأول هو القلب النابض للحركة الأولى بل للسيمفونية كلها يقدمه بيتهوڤن على كافة آلات الأوركسترا بمصاحبة الكلارينيت.[3]

بدأ بيتهوڤن فى كتابة السيمفونية عام 1805 وانتهى منها عام 1808 كان ذلك بعد كتابة السيمفونية الثالثة ولكنه انصرف عنها فى غمار حبه لخطيبته تريزا فون برونشفيك.

العرض الأول

The Fifth Symphony was premiered on 22 December 1808 at a mammoth concert at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna consisting entirely of Beethoven premieres, and directed by Beethoven himself on the conductor's podium.[4] The concert lasted for more than four hours. The two symphonies appeared on the programme in reverse order: the Sixth was played first, and the Fifth appeared in the second half.[5] The programme was as follows:

- السيمفونية السادسة

- آريا: Ah! perfido, Op. 65

- The Gloria movement of the Mass in C major

- كونشرتو الپيانو الرابع (played by Beethoven himself)

- (Intermission)

- السيمفونية الخامسة

- The Sanctus and Benedictus movements of the C major Mass

- A solo piano improvisation من بيتهوڤن نفسه

- The Choral Fantasy

Beethoven dedicated the Fifth Symphony to two of his patrons, Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky. The dedication appeared in the first printed edition of April 1809.

الاستقبال والتأثير

الآلات الموسيقية

- آلات النفخ الخشبية

- 1 piccolo (الحركة الرابعة فقط)

- 2 flutes

- 2 oboes

- 2 clarinets in B♭ (first, second, and third movements) and C (fourth movement)

- 2 bassoons

- 1 contrabassoon (fourth movement only)

Lore

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, scholarly articles, and program notes for live and recorded performances. This section summarizes some themes that commonly appear in this material.

موتيفة القدَر

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of Fate knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven's secretary and factotum Anton Schindler, who wrote, many years after Beethoven's death:

The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author's presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: "Thus Fate knocks at the door!"[6]

Schindler's testimony concerning any point of Beethoven's life is disparaged by experts (he is believed to have forged entries in Beethoven's so-called "conversation books", the books in which the deaf Beethoven got others to write their side of conversations with him).[7] Moreover, it is often commented that Schindler offered a highly romanticized view of the composer.

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from Antony Hopkins's description of the symphony.[8] Carl Czerny (Beethoven's pupil, who premiered the "Emperor" Concerto in Vienna) claimed that "the little pattern of notes had come to [Beethoven] from a yellow-hammer's song, heard as he walked in the Prater-park in Vienna." Hopkins further remarks that "given the choice between a yellow-hammer and Fate-at-the-door, the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though Czerny's account is too unlikely to have been invented."

In his Omnibus television lecture series in 1954, Leonard Bernstein likened the Fate Motif to the four note coda common to symphonies. These notes would terminate the symphony as a musical coda, but for Beethoven they become a motif repeating throughout the work for a very different and dramatic effect, he says.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. "The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest 'Fate Knocking at the gate' is apocryphal; Beethoven's pupil, Ferdinand Ries, was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him."[9] Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner remarks that "Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests"; this might be taken to impugn both tales.[10]

اختيار بيتهوفن للمفاتيح

The key of the Fifth Symphony, C minor, is commonly regarded as a special key for Beethoven, specifically a "stormy, heroic tonality".[11] Beethoven wrote a number of works in C minor whose character is broadly similar to that of the Fifth Symphony. Pianist and writer Charles Rosen says,

Beethoven in C minor has come to symbolize his artistic character. In every case, it reveals Beethoven as Hero. C minor does not show Beethoven at his most subtle, but it does give him to us in his most extroverted form, where he seems to be most impatient of any compromise.[12]

تكرار الموتيفة الافتتاحية طوال السيمفونية

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. "It is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony" (Doug Briscoe[13]); "a single motif that unifies the entire work" (Peter Gutmann[14]); "the key motif of the entire symphony";[15] "the rhythm of the famous opening figure ... recurs at crucial points in later movements" (Richard Bratby[16]). The New Grove encyclopedia cautiously endorses this view, reporting that "[t]he famous opening motif is to be heard in almost every bar of the first movement—and, allowing for modifications, in the other movements."[17]

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly:

In the second movement, an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm:

line 6 - column 35:

GUILE signaled an error for the expression beginning here

In the finale, Doug Briscoe[13] suggests that the motif may be heard in the piccolo part, presumably meaning the following passage:

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following:

On the other hand, some commentators are unimpressed with these resemblances and consider them to be accidental. Antony Hopkins,[8] discussing the theme in the scherzo, says "no musician with an ounce of feeling could confuse [the two rhythms]", explaining that the scherzo rhythm begins on a strong musical beat whereas the first-movement theme begins on a weak one. Donald Tovey[18] pours scorn on the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: "This profound discovery was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough." Applied consistently, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other works by Beethoven are also "unified" with this symphony, as the motif appears in the "Appassionata" piano sonata, the Fourth Piano Concerto (listen ), and in the String Quartet, Op. 74. Tovey concludes, "the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art."

To Tovey's objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven's older Classical contemporaries such as Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, it is found in Haydn's "Miracle" Symphony, No. 96 (listen ) and in Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503 (listen ). Such examples show that "short-short-short-long" rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven's day.

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins's words) "remain eternally open to debate."[8]

Use of La Folia

Folia is a dance form with a distinctive rhythm and harmony, which was used by many composers from the Renaissance well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, often in the context of a theme and variations.[19] It was used by Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony in the harmony midway through the slow movement (bars 166–177).[20] Although some recent sources mention that the fragment of the Folia theme in Beethoven's symphony was detected only in the 1990s, Reed J. Hoyt analyzed some Folia-aspects in the oeuvre of Beethoven already in 1982 in his "Letter to the Editor", in the journal College Music Symposium 21, where he draws attention to the existence of complex archetypal patterns and their relationship.[21]

Trombones and piccolos

It is a common misconception that the last movement of Beethoven's Fifth is the first time the trombone and the piccolo were used in a concert symphony. In 1807, the Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert had specified trombones for his Symphony No. 3 in E♭ major,[22] and examples of earlier symphonies with a part for piccolo abound, including Michael Haydn's Symphony No. 18 in C major, composed in August 1773.[بحاجة لمصدر]

التأثيرات

الحركات

النسخ

- The edition by Jonathan Del Mar mentioned above was published as follows: Ludwig van Beethoven. Symphonies 1–9. Urtext. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1996–2000, ISMN M-006-50054-3.

- An inexpensive version of the score has been issued by Dover Publications. This is a 1989 reprint of an old edition (Braunschweig: Henry Litolff, no date).[23]

في الثقافة العامة

مرئيات

| مئات الطلبة يعزفون بأجسادهم السيمفونية الخامسة مدرسة سان-ميشل-گاريكوا في كامبو ببلد الباسك الفرنسي. جائحة كورونا منعت الطلبة من الغناء، فقاموا بأداء النوتة الموسيقية الجسدية صممتها مدرسة الموسيقى الأداء الإيقاعي صـُوِّر في حدائق أرناگا البديعة، أمام |

الهامش

- ^ Schauffler, Robert Haven (1933). Beethoven: The Man Who Freed Music. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran, & Company. p. 211.

- ^ "قصة السيمفونية الخامسة لبيتهوفن". محبي الموسيقى. 2021-06-20. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ "السيمفونية الخامسة لبيتهوفن ولماذا تحتفل جوجل بها؟". البيان. 2015-12-17. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ Kinderman, William (1995). Beethoven. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-520-08796-8.

- ^ Parsons, Anthony (1990). "Symphonic birth-pangs of the trombone". British Trombone Society. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Jolly, Constance (1966). Beethoven as I Knew Him. London: Faber and Faber. As translated from Schindler (1860). Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven.

- ^ Cooper, Barry (1991). The Beethoven Compendium. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-681-07558-9.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhopkins - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةScherman570 - ^ Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner. "Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 5, Op. 67". Classical Music Pages. Archived from the original on 2009-07-06.

- ^ Wyatt, Henry. "Mason Gross Presents—Program Notes: 14 June 2003". Mason Gross School of Arts. Archived from the original on 1 سبتمبر 2006.

- ^ Rosen, Charles (2002). Beethoven's Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 134.

- ^ أ ب Briscoe, Doug. "Program Notes: Celebrating Harry: Orchestral Favorites Honoring the Late Harry Ellis Dickson". Boston Classic Orchestra. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

- ^ Gutmann, Peter. "Ludwig Van Beethoven: Fifth Symphony". Classical Notes.

- ^ "Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. The Destiny Symphony". All About Beethoven.

- ^ Bratby, Richard. "Symphony No. 5". Archived from the original on 31 August 2005.

- ^ "Ludwig van Beethoven". Grove Online Encyclopedia.

- ^ Tovey, Donald Francis (1935). Essays in Musical Analysis, Volume 1: Symphonies. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "What is La Folia?". folias.nl. 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Bar 166". folias.nl. 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Which versions of La Folia have been written down, transcribed or recorded?". folias.nl. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Kallai, Avishai. "Revert to Eggert". Retrieved 28 April 2006.

- ^ Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, and 7 in Full Score (Ludwig van Beethoven). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26034-8.

- ^ Kyle Macdonald (2021-06-19). "Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, but as a body percussion epic played by hundreds of schoolchildren". classicfm.com.

للاستزادة

- Guerrieri, Matthew (2012). The First Four Notes: Beethoven's Fifth and the Human Imagination. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307593283.

وصلات خارجية

- Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 - A Beginners' Guide - Overview, analysis and the best recordings - The Classic Review

- General discussion and reviews of recordings

- Brief structural analysis

- Analysis of the Beethoven 5th Symphony, The Symphony of Destiny on the All About Ludwig van Beethoven Page

- Program notes for a performance by the National Symphony Orchestra, Washington, DC.

- Project Gutenberg has two MIDI-versions of Beethoven's 5th symphony: Etext No. 117 and Etext No. 156

- Program notes for a performance & lecture by Jeffrey Kahane and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

- Sketch to the Scherzo from op. 67 Fifth Symphony from Eroica Skbk (1803) – Unheard Beethoven Website

- Original Finale in c minor to Fifth Symphony op. 67, Gardi 23 (1804) – Unheard Beethoven Website

النوتات

- [[scores:Category:{{{id}}}|Free scores by Symphony No. 5]] at the International Music Score Library Project

- Mutopia project has a piano reduction score of Beethoven's 5th Symphony

- Public domain sheet music both typset and scanned on Cantorion.org

- Full Score of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony from Indiana University

قالب:Beethoven symphonies قالب:Disney's Fantasia قالب:Voyager Golden Record

- الصفحات التي تستخدم سمات النقاط المهملة

- Pages which use score

- صفحات بها خطأ في تحويل الحرز

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2021

- مؤلفات موسيقية في 1808

- سيمفونيات لودڤيگ ڤان بيتهوڤن

- Segments from Fantasia 2000

- مؤلفات موسيقية على سلم دو الصغير

- Music dedicated to benefactors or patrons

- Music dedicated to nobility or royalty

- Contents of the Voyager Golden Record

![{\clef treble \key c \minor \tempo "Allegro con brio" 2=108 \time 2/4 {r8 g'\ff[ g' g'] | ees'2\fermata | r8 f'[ f' f'] | d'2~ | d'\fermata | } }](/w/images/lilypond/a/c/ac16qsl6tsw76hf059bkvqy3jrwlsdw/ac16qsl6.png)

![\relative c'' {

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn"

\key c \minor

\time 3/4

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #19

\bar ""

\[ g4\ff^"a 2" g g | g2. | \]

g4 g g | g2. |

g4 g g | <es g>2. |

<g bes>4(<f as>) <es g>^^ | <bes f'>2. |

}](/w/images/lilypond/j/f/jfvbaitdav2wpprlg7rt4oe6ldwn75c/jfvbaitd.png)

![\new StaffGroup <<

\new Staff \relative c'' {

\time 4/4

\key c \major

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #244

\bar ""

r8^"Piccolo" \[ fis g g g2~ \] |

\repeat unfold 2 {

g8 fis g g g2~ |

}

g8 fis g g g2 |

}

\new Staff \relative c {

\clef "bass"

b2.^"Viola, Cello, Bass" g4(|

b4 g d' c8. b16) |

c2. g4(|

c4 g e' d8. c16) |

}

>>](/w/images/lilypond/r/z/rzn0o01ee74i4lkn37hrgsdgkhycysg/rzn0o01e.png)

![\new StaffGroup <<

\new Staff \relative c' {

\time 2/2

\key c \major

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #362

\bar ""

\tempo "Presto"

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5

c2.\fp^"Violins" b4 | a(g) g-. g-. |

c2. b4 | a(g) g-. g-. |

\repeat unfold 2 {

<c e>2. <b d>4 | <a c>(<g b>) q-. q-. |

}

}

\new Staff \relative c {

\time 2/2

\key c \major

\clef "bass"

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5

c4\fp^"Bass instruments" r r2 | r4 \[ g g g |

c4\fp \] r r2 | r4 g g g |

\repeat unfold 2 {

c4\fp r r2 | r4 g g g |

}

}

>>](/w/images/lilypond/q/j/qjt2hacnh0166c2vwx8gccqx16asf3o/qjt2hacn.png)