إستونيا

إستونيا Estonia ( /ɛˈstoʊniə/;[7][8] الإستونية: [Eesti] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [ˈeːsti])، رسمياً جمهورية إستونيا (الإستونية: [Eesti Vabariik] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))، هي بلد في منطقة البلطيق بشمال أوروپا. يحدها من الشمال خليج فنلندا، ومن الغرب بحر البلطيق، ومن الجنوب لاتڤيا (343 كم)، ومن الشرق بحيرة پيپوس وروسيا (338.6 كم).[9] عبر بحر البلطيق تقع السويد في الغرب وفنلندا في الشمال. تتألف أراضي إستونيا من البر الرئيسي وأكثر من 1500 جزيرة صغيرة وكبيرة في بحر البلطيق، ويشغل البر مساحة 45227 كم²، وتتأثر البلاد بالمناخ القاري الرطب. The territory of Estonia consists of the mainland, the larger islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa, and over 2,200 other islands and islets on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea,[10] covering a total area of 45,339 square kilometres (17,505 sq mi). The capital city Tallinn and Tartu are the two largest urban areas of the country. The Estonian language is the indigenous and the official language of Estonia; it is the first language of the majority of its population, as well as the world's second most spoken Finnic language.

جمهورية إستونيا Eesti Vabariik (إستونية) | |

|---|---|

![موقع إستونيا (dark green) – on the European continent (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) — [Legend]](/w/images/thumb/a/a2/EU-Estonia.svg/350px-EU-Estonia.svg.png) موقع إستونيا (dark green) – on the European continent (green & dark grey) | |

| العاصمة و أكبر مدينة | تالين 59°25′N 24°45′E / 59.417°N 24.750°E |

| Official language | Estonian |

| Ethnic groups (2023) | |

| الدين (2021[1]) |

|

| صفة المواطن | Estonian |

| الحكومة | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Alar Karis | |

| Kaja Kallas | |

| التشريع | Riigikogu |

| Independence | |

| 23–24 February 1918 | |

• Joined the League of Nations | 22 September 1921 |

| 1940–1991 | |

| 20 August 1991 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| المساحة | |

• الإجمالية | 45,339 km2 (17,505 sq mi) (129thd) |

• الماء (%) | 4.6 |

| التعداد | |

• تقدير 2023 | |

• إحصاء 2021 | 1,331,824[3] |

• الكثافة | 30.6/km2 (79.3/sq mi) (148th) |

| ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $61.757 billion[4] (113th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $46,385 [4] (40th) |

| ن.م.إ. (الإسمي) | تقدير 2023 |

• الإجمالي | ▲ $41.55 billion[4] (102th) |

• للفرد | ▲ $31,207[4] (37th) |

| جيني (2021) | ▲ 30.6[5] medium |

| م.ت.ب. (2021) | ▲ 0.890[6] very high · 31st |

| العملة | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| التوقيت | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

• الصيفي (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| جانب السواقة | right |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +372 |

| النطاق العلوي للإنترنت | .ee |

| |

The land of what is now modern Estonia has been inhabited by Homo sapiens since at least 9,000 BC. The medieval indigenous population of Estonia was one of the last pagan civilisations in Europe to adopt Christianity following the Papal-sanctioned Livonian Crusade in the 13th century.[11] After centuries of successive rule by the Teutonic Order, Denmark, Sweden, and the Russian Empire, a distinct Estonian national identity began to emerge in the mid-19th century. This culminated in the 24 February 1918 Estonian Declaration of Independence from the then warring Russian and German Empires. Democratic throughout most of the interwar period, Estonia declared neutrality at the outbreak of World War II, but the country was repeatedly contested, invaded and occupied, first by the Soviet Union in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in 1941, and was ultimately reoccupied in 1944 by, and annexed into, the USSR as an administrative subunit (Estonian SSR). Throughout the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation,[12] Estonia's de jure state continuity was preserved by diplomatic representatives and the government-in-exile. Following the bloodless Estonian "Singing Revolution" of 1988–1990, the nation's de facto independence from the Soviet Union was restored on 20 August 1991.

إستونيا هي جمهورية برلمانية ديمقراطية تنقسم إلى خمسة عشر مقاطعة، عاصمتها وأكبر مدنها تالين. بعدد سكان يبلغ 1.3 مليون نسمة، تعتبر واحدة من أقل دول الاتحاد الأوروپي منطقة اليورو، الناتو ومنطقة تشنگن إكتظاظاً بالسكان. الإستونيون هم شعب فنلندي، واللغة الرسمية هي الإستونية، وهي من اللغات الفنلندية الأوگرية شديدة القرب بالفنلندية واللغات السامية، وتختلف بشكل كبير عن المجرية.

كبلد متطور يتمتع باقتصاد متقدم عالي الدخل[13] ومعايير معيشة مترفعة، تحتل إستونية ترتيب متقدم على [[قائمة البلدان حسب مؤشر التنمية البشرية|مؤشر التنمية البشرية] (31 من 191)،[14] sovereign state of Estonia is a democratic unitary parliamentary republic, administratively subdivided into 15 maakond (counties). With a population of just about 1.4 million, it is one of the least populous members of the European Union, the Eurozone, the OECD, the Schengen Area, and NATO. Estonia has consistently ranked highly in international rankings for quality of life,[15] education,[16] press freedom, digitalisation of public services[17][18] and the prevalence of technology companies.[19]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصل التسمية

إحدى النظريات هي أن الاسم الحديث لإستونيا نشأ من Aesti التي وصفها المؤرخ الروماني تاسيتوس في جرمانيا له (حوالي 98 م).[20]

من ناحية أخرى، الملاحم الإسكندنافية القديمة تشير إلى الأرض ودعا إستلاند، على مقربة من والألمانية الدانمركية والهولندية إستلاند السويدية والنرويجية، الأجل للبلد. النسخ القديمة اللاتينية في وقت مبكر وغيرها من الاسم هي إستيا وهيستيا. [بحاجة لمصدر]

إستونيا كان مشترك الهجاء الإنجليزية البديل قبل الاستقلال.[21][22]

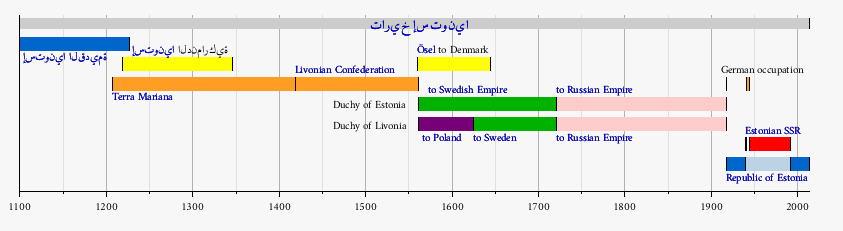

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ وعصر الڤايكنج

Human settlement in Estonia became possible 13,000–11,000 years ago, when the ice from the last glacial era melted. The oldest known settlement in Estonia is the Pulli settlement, on the banks of Pärnu river in southwest Estonia. According to radiocarbon dating, it was settled around 11,000 years ago.[23]

The earliest human habitation during the Mesolithic period is connected to the Kunda culture. At that time the country was covered with forests, and people lived in semi-nomadic communities near bodies of water. Subsistence activities consisted of hunting, gathering and fishing.[24] Around 4900 BC, ceramics appear of the neolithic period, known as Narva culture.[25] Starting from around 3200 BC the Corded Ware culture appeared; this included new activities like primitive agriculture and animal husbandry.[26]

The Bronze Age started around 1800 BC, and saw the establishment of the first hill fort settlements.[28] A transition from hunter-fisher subsistence to single-farm-based settlement started around 1000 BC, and was complete by the beginning of the Iron Age around 500 BC.[23][29] The large amount of bronze objects indicate the existence of active communication with Scandinavian and Germanic tribes.[30]

The middle Iron Age produced threats appearing from different directions. Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when in the early 7th century "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed Ingvar, the King of Swedes.[31][بحاجة لمصادر إضافية] Similar threats appeared to the east, where East Slavic principalities were expanding westward. Around 1030 the troops of Kievan Rus led by Yaroslav the Wise defeated Estonians and established a fort in modern-day Tartu. This foothold may have lasted until ca 1061 when an Estonian tribe, the Sosols, destroyed it.[32][33][34][35] Around the 11th century, the Scandinavian Viking era around the Baltic Sea was succeeded by the Baltic Viking era, with seaborne raids by Curonians and by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, known as Oeselians. In 1187 Estonians (Oeselians), Curonians or/and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, which was a major city of Sweden at the time.[36][37]

وقعت إستونيا على مر التاريخ تحت سيطرة الدانماركيين، والسويديين، والألمان والروس حتى عام 1918 حيث تم إعلان الاستقلال. اعترفت الأخيرة بإستونيا عام 1920 وأُعلن قيام جمهورية برلمانية و تأميم أراضي النُبلاء في نفس العام. انضمت دول البلطيق الثلاث اللى عصبة الأمم المتحدة عام 1921. عاشت استونيا في الفترة 1921 إلى 1940 فترة سياسية غير مستقرة أهم أحداثها تشكيل حكومة فاشية برئاسة قسطنطين باتس (Päts) عام 1934. اتفاق هتلر-ستالين عام 1939 أعطى الضوء الأخضر للاتحاد السوفياتي باحتلال جمهوريات البلطيق و من ضمنها استونيا، الذي تم في عام 1940 أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية (1939-1945) بدون أي سابق انذار. بعد نشوب الحرب بين ألمانيا والاتحاد السوفيتي، قامت الأولى بإحتلال جمهوريات البلطيق عام 1941، إلى أن أعاد الجيش الأحمر إحتلالهم و إعادتهم تحت سيطرة الاتحاد السوفيتي.

بقي تاريخ البلاد جزء من التاريخ السوفيتي في السنوات المقبلة حتى الأعوام 1988 - 1990، عندما بدأ الاتحاد السوفيتي بالانهيار وتزايد الأصوات المطالبة باستقلال البلاد. وأعلنت إستونيا استقلالها عام 1990، واعترف مجلس السوفيت الأعلى في العام التالي بالجمهورية الجديدة. انضمت إستونيا إلى الأمم المتحدة عام 1992 وإلى الاتحاد الاوروبي عام 2004.

عصر الڤايكنگ

إستونيا الدنماركية

العصور الوسطى

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

إستونيا السويدية

الصحوة الوطنية والامبراطورية الروسية

National Awakening

The Estonian national awakening began in the 1850s as several leading figures started promoting an Estonian national identity among the general populace. Widespread farm buyouts by Estonians and the resulting rapidly growing class of land-owning farmers provided the economic basis for the formation of this new "Estonian identity". In 1857 Johann Voldemar Jannsen started publishing the first Estonian language daily newspaper and began popularising the denomination of oneself as eestlane (Estonian).[38] Schoolmaster Carl Robert Jakobson and clergyman Jakob Hurt became leading figures in a national movement, encouraging Estonian farmers to take pride in their ethnic Estonian identity.[39] The first nationwide movements formed, such as a campaign to establish the Estonian language Alexander School, the founding of the Society of Estonian Literati and the Estonian Students' Society, and the first national song festival, held in 1869 in Tartu.[40][41][42] Linguistic reforms helped to develop the Estonian language.[43] The national epic Kalevipoeg was published in 1862, and 1870 saw the first performances of Estonian theatre.[44][45] In 1878 a major split happened in the national movement. The moderate wing led by Hurt focused on development of culture and Estonian education, while the radical wing led by Jakobson started demanding increased political and economical rights.[41]

At the end of the 19th century, Russification began, as the central government initiated various administrative and cultural measures to tie Baltic governorates more closely to the empire.[40] The Russian language replaced German and Estonian in most secondary schools and universities, and many social and cultural activities in local languages were suppressed.[45] In the late 1890s, there was a new surge of nationalism with the rise of prominent figures like Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts. In the early 20th century, Estonians started taking over control of local governments in towns from Germans.[46]

During the 1905 Revolution, the first legal Estonian political parties were founded. An Estonian national congress was convened and demanded the unification of Estonian areas into a single autonomous territory and an end to Russification. The unrest was accompanied by both peaceful political demonstrations and violent riots with looting in the commercial district of Tallinn and in a number of wealthy landowners' manors in the Estonian countryside. The Tsarist government responded with a brutal crackdown; some 500 people were executed and hundreds more jailed or deported to Siberia.[47][48]

Independence

In 1917, after the February Revolution, the governorate of Estonia was expanded by the Russian Provisional Government to include Estonian-speaking areas of Livonia and was granted autonomy, enabling the formation of the Estonian Provincial Assembly.[49] The Bolsheviks seized power in Estonia in November 1917, and the Provincial Assembly was disbanded. However, the Provincial Assembly established the Salvation Committee, and during the short interlude between Russian retreat and German arrival, the committee declared independence on 24 February 1918, and formed the Estonian Provisional Government. German occupation immediately followed, but after their defeat in World War I, the Germans were forced to hand over power back to the Provisional Government on 19 November 1918.[50][51]

On 28 November 1918 Soviet Russia invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence.[52] The Red Army came within 30 km of Tallinn, but in January 1919, the Estonian Army, led by Johan Laidoner, went on a counter-offensive, ejecting Bolshevik forces from Estonia within a few months. Renewed Soviet attacks failed, and in spring, the Estonian army, in co-operation with White Russian forces, advanced into Russia and Latvia.[53][54] In June 1919, Estonia defeated the German Landeswehr which had attempted to dominate Latvia, restoring power to the government of Kārlis Ulmanis there. After the collapse of the White Russian forces, the Red Army launched a major offensive against Narva in late 1919, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. On 2 February 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed by Estonia and Soviet Russia, with the latter pledging to permanently give up all sovereign claims to Estonia.[53][55]

In April 1919, the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected. The Constituent Assembly passed a sweeping land reform expropriating large estates, and adopted a new highly liberal constitution establishing Estonia as a parliamentary democracy.[56][57] In 1924, the Soviet Union organised a communist coup attempt, which quickly failed.[58] Estonia's cultural-autonomy law for ethnic minorities, adopted in 1925, is widely recognised as one of the most liberal in the world at that time.[59] The Great Depression put heavy pressure on Estonia's political system, and in 1933, the right-wing Vaps movement spearheaded a constitutional reform establishing a strong presidency.[60][61] On 12 March 1934 the acting head of state, Konstantin Päts, declared a state of emergency, under the pretext that the Vaps movement had been planning a coup. Päts, together with general Johan Laidoner and Kaarel Eenpalu, established an authoritarian régime during the "era of silence", when the parliament did not reconvene and the newly established Patriotic League became the only legal political movement.[62] A new constitution was adopted in a referendum, and elections were held in 1938. Both pro-government and opposition candidates were allowed to participate, but only as independents.[63] The Päts régime was relatively benign compared to other authoritarian régimes in interwar Europe, and the régime never used violence against political opponents.[64]

Estonia joined the League of Nations in 1921.[65] Attempts to establish a larger alliance together with Finland, Poland, and Latvia failed, with only a mutual-defence pact being signed with Latvia in 1923, and later was followed up with the Baltic Entente of 1934.[66][67] In the 1930s, Estonia also engaged in secret military co-operation with Finland.[68] Non-aggression pacts were signed with the Soviet Union in 1932, and with Germany in 1939.[65][69] In 1939, Estonia declared neutrality, but this proved futile in World War II.[70]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الحرب العالمية الثانية

A week before the outbreak of World War II, on 23 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. In the pact's secret protocol Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland were divided between USSR and Germany into "spheres of influence", with Estonia assigned to the Soviet "sphere".[71] On 24 September 1939, the Soviet Union demanded that Estonia sign a treaty of "mutual assistance" which would allow the Soviet Union to establish military bases in the country. The Estonian government felt that it had no choice but to comply, and the Soviet–Estonian Mutual Assistance Treaty was signed on 28 September 1939.[72] On 14 June, the Soviet Union instituted a full naval and air blockade on Estonia. On the same day, the airliner Kaleva was shot down by the Soviet Air Force. On 16 June, the USSR presented an ultimatum demanding completely free passage of the Red Army into Estonia and the establishment of a pro-Soviet government. Feeling that resistance was hopeless, the Estonian government complied and, on the next day, the whole country was occupied.[73][74] On 6 August 1940, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union as the Estonian SSR.[75]

The USSR established a repressive wartime regime in occupied Estonia. Many of the country's high-ranking civil and military officials, intelligentsia and industrialists were arrested. Soviet repressions culminated on 14 June 1941 with mass deportation of around 11,000 people to Russia.[76][77] When Operation Barbarossa (accompanied by Estonian guerrilla soldiers called "Forest Brothers"[78]) began against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 in the form of the "Summer War" (الإستونية: [Suvesõda] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), around 34,000 young Estonian men were forcibly drafted into the Red Army, fewer than 30% of whom survived the war. Soviet destruction battalions initiated a scorched earth policy. Political prisoners who could not be evacuated were executed by the NKVD.[79][80] Many Estonians went into the forest, starting an anti-Soviet guerrilla campaign. In July, German Wehrmacht reached south Estonia. The USSR evacuated Tallinn in late August with massive losses, and capture of the Estonian islands was completed by German forces in October.[81]

Initially, many Estonians were hopeful that Germany would help to restore Estonia's independence, but this soon proved to be in vain. Only a puppet collaborationist administration was established, and occupied Estonia was merged into Reichskommissariat Ostland, with its economy being fully subjugated to German military needs.[82] About a thousand Estonian Jews who had not managed to leave were almost all quickly killed in 1941. Numerous forced labour camps were established where thousands of Estonians, foreign Jews, Romani, and Soviet prisoners of war perished.[83] German occupation authorities started recruiting men into small volunteer units but, as these efforts provided meagre results and military situation worsened, forced conscription was instituted in 1943, eventually leading to formation of the Estonian Waffen-SS division.[84] Thousands of Estonians who did not want to fight in the German military secretly escaped to Finland, where many volunteered to fight together with Finns against Soviets.[85]

The Red Army reached the Estonian borders again in early 1944, but its advance into Estonia was stopped in heavy fighting near Narva for six months by German forces, including numerous Estonian units.[86] In March, the Soviet Air Force carried out heavy bombing raids against Tallinn and other Estonian towns.[87] In July, the Soviets started a major offensive from the south, forcing the Germans to abandon mainland Estonia in September and the Estonian islands in November.[86] As German forces were retreating from Tallinn, the last pre-war prime minister Jüri Uluots appointed a government headed by Otto Tief in an unsuccessful attempt to restore Estonia's independence.[88] Tens of thousands of people, including most of the Estonian Swedes, fled westwards to avoid the new Soviet occupation.[89]

Overall, Estonia lost about 25% of its population through deaths, deportations and evacuations in World War II.[90] Estonia also suffered some irrevocable territorial losses, as the Soviet Union transferred border areas comprising about 5% of Estonian pre-war territory from the Estonian SSR to the Russian SFSR.[91]

Second Soviet occupation

Thousands of Estonians opposing the second Soviet occupation joined a guerrilla movement known as the "Forest Brothers". The armed resistance was heaviest in the first few years after the war, but Soviet authorities gradually wore it down through attrition, and resistance effectively ceased to exist in the mid-1950s.[92] The Soviets initiated a policy of collectivisation, but as farmers remained opposed to it a campaign of terror was unleashed. In March 1949 about 20,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia. Collectivization was fully completed soon afterwards.[76][93]

The Russian-dominated occupation authorities under the Soviet Union began Russification, with hundreds of thousands of ethnic Russians and other "Soviet people" being induced to settle in occupied Estonia, in a process which eventually threatened to turn indigenous Estonians into a minority in their own native land.[94] In 1945 Estonians formed 97% of the population, but by 1989 their share of the population had fallen to 62%.[95] Occupying authorities carried out campaigns of ethnic cleansing, mass deportation of indigenous populations, and mass colonization by Russian settlers which led to Estonia losing 3% of its native population.[96] By March 1949, 60,000 people were deported from Estonia and 50,000 from Latvia to the gulag system in Siberia, where death rates were 30%. The occupying regime established an Estonian Communist Party, where Russians were the majority in party membership.[97] Economically, heavy industry was strongly prioritised, but this did not improve the well-being of the local population, and caused massive environmental damage through pollution.[98] Living standards under the Soviet occupation kept falling further behind nearby independent Finland.[94] The country was heavily militarised, with closed military areas covering 2% of territory.[99] Islands and most of the coastal areas were turned into a restricted border zone which required a special permit for entry.[100] Estonia was quite closed until the second half of the 1960s, when gradually Estonians began to covertly watch Finnish television in the northern parts of the country, thus getting a better picture of the way of life behind the Iron Curtain.[101]

The majority of Western countries considered the annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union illegal.[102] Legal continuity of the Estonian state was preserved through the government-in-exile and the Estonian diplomatic representatives which Western governments continued to recognise.[103][104]

Independence restored

The introduction of perestroika by the central government of the Soviet Union in 1987 made open political activity possible again in Estonia, which triggered an independence restoration process later known as Laulev revolutsioon ("Singing revolution").[105] The environmental Fosforiidisõda ("Phosphorite war") campaign became the first major protest movement against the central government.[106] In 1988, new political movements appeared, such as the Popular Front of Estonia, which came to represent the moderate wing in the independence movement, and the more radical Estonian National Independence Party, which was the first non-communist party in the Soviet Union and demanded full restoration of independence.[107] On 16 November 1988, after the first non-rigged multi-candidate elections in half a century, the parliament of Soviet-controlled Estonia issued the Sovereignty Declaration, asserting the primacy of Estonian laws. Over the next two years, many other administrative parts (or "republics") of the USSR followed the Estonian example, issuing similar declarations.[108][109] On 23 August 1989, about 2 million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians participated in a mass demonstration, forming the Baltic Way human chain across the three countries.[110] In February 1990, elections were held to form the Congress of Estonia.[111] In March 1991, a referendum was held where 78.4% of voters supported full independence. During the coup attempt in Moscow, Estonia declared restoration of independence on 20 August 1991.[112]

Soviet authorities recognised Estonian independence on 6 September 1991, and on 17 September Estonia was admitted into the United Nations.[113] The last units of the Russian army left Estonia in 1994.[114]

In 1992 radical economic reforms were launched for switching over to a market economy, including privatisation and currency reform.[115] Estonia has been a member of the WTO since 13 November 1999.[116]

Since regaining independence in 1991, Estonian foreign policy has been aligned with other Western democracies, and in 2004 Estonia joined both the European Union and NATO.[117] On 9 December 2010, Estonia became a member of OECD.[118] On 1 January 2011, Estonia joined the eurozone and adopted the euro, the single currency of EU.[119] Estonia was a member of the UN Security Council 2020–2021.[120]

الاحتلال الألماني

إستونيا السوڤيتية

ما بعد الاستقلال

خط زمني

|

الجغرافيا

تقع استونيا بين خطوط العرض 57.3 و 59.5 و خطوط الطول 21.5 و 28.1 على الساحل الشرقي لبحر البلطيق، في شمال شرق أوروبا. معدل علو الارتفاعات يبلغ 50 متر. أعلى جبل هو سور مونامغي (Suur Munamägi) و يبلغ 318 متر. الغابات تُشكل 47% من مساحة البلاد، اللتي تُعد بجانب الحجر الكلسي أهم موارد البلاد. تحتضن استونيا أكثر من 1400 بحيرة، معظمها صغيرة الحجم و أكبرها بحيرة هي بايبسي (Peipsi) بمساحة قدرها 3555 كم مربع. طول ساحل البلاد يزاهي ال 3794 كم (مع الجزر). يبلغ عدد الجزر الاستونية حوالي 1500 جزيرة.

Osmussaar is one of many islands in the territorial waters of Estonia.

Duckboards along a hiking trail in Viru bog in Lahemaa National Park. The longest hiking trail is 627 km (390 mi) long.[122]

Climate

Estonia is situated in the temperate climate zone, and in the transition zone between maritime and continental climate, characterized by warm summers and fairly mild winters. Primary local differences are caused by the Baltic Sea, which warms the coastal areas in winter, and cools them in the spring.[123][124] Average temperatures range from 17.8 °C (64.0 °F) in July, the warmest month, to −3.8 °C (25.2 °F) in February, the coldest month, with the annual average being 6.4 °C (43.5 °F).[125] The highest recorded temperature is 35.6 °C (96.1 °F) from 1992, and the lowest is −43.5 °C (−46.3 °F) from 1940.[126] The annual average precipitation is 662 millimetres (26.1 in),[127] with the daily record being 148 millimetres (5.8 in).[128] Snow cover varies significantly on different years.[124] Prevailing winds are westerly, southwesterly, and southerly, with average wind speed being 3–5 m/s inland and 5–7 m/s on coast.[124] The average monthly sunshine duration ranges from 290 hours in August, to 21 hours in December.[129]

Biodiversity

Due to varied climatic and soil conditions, and plethora of sea and internal waters, Estonia is one of the most biodiverse regions among the similar sized territories at the same latitude.[124] Many species extinct in most other European countries can be still found in Estonia.[130]

Recorded species include 64 mammals, 11 amphibians, and 5 reptiles.[123] Large mammals present in Estonia include the grey wolf, lynx, brown bear, red fox, badger, wild boar, moose, roe deer, beaver, otter, grey seal, and ringed seal. The critically endangered European mink has been successfully reintroduced to the island of Hiiumaa, and the rare Siberian flying squirrel is present in east Estonia.[130] The red deer, once extirpated, has also been successfully reintroduced.[131] In the beginning of the 21st century, an isolated population of European jackals was confirmed in Western Estonia, much further north than their earlier known range. The number of jackals has grown quickly in coastal areas of Estonia and can be found in Matsalu National Park.[132][133] Introduced mammals include sika deer, fallow deer, raccoon dog, muskrat, and American mink.[123]

Over 300 bird species have been found in Estonia, including the white-tailed eagle, lesser spotted eagle, golden eagle, western capercaillie, black and white stork, numerous species of owls, waders, geese and many others.[134] The barn swallow is the national bird of Estonia.[135]

Phytogeographically, Estonia is shared between the Central European and Eastern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Estonia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests.[136] Estonia has a rich composition of floristic groups, with estimated 6000 (3461 identified) fungi, 3000 (2500 identified) algae and cyanobacteria, 850 (786 identified) lichens, and 600 (507 identified) bryophytes. Forests cover approximately half of the country. 87 native and over 500 introduced tree and bush species have been identified, with most prevalent tree species being pine (41%), birch (28%), and spruce (23%).[123] Since 1969, the cornflower (Centaurea cyanus) has been the national flower of Estonia.[137]

Protected areas cover 19.4% of Estonian land and 23% of its total area together with territorial sea. Overall there are 3,883 protected natural objects, including 6 national parks, 231 nature conservation areas, and 154 landscape reserves.[138]

السياسة

Estonia is a unitary parliamentary republic. The unicameral parliament Riigikogu serves as the legislative and the government as the executive.[139]

Estonian parliament Riigikogu is elected by citizens over 18 years of age for a four-year term by proportional representation, and has 101 members. Riigikogu's responsibilities include approval and preservation of the national government, passing legal acts, passing the state budget, and conducting parliamentary supervision. On proposal of the president Riigikogu appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the chairman of the board of the Bank of Estonia, the Auditor General, the Legal Chancellor, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.[140][141]

The Government of Estonia is formed by the Prime Minister of Estonia at recommendation of the President, and approved by the Riigikogu. The government, headed by the Prime Minister, carries out domestic and foreign policy. Ministers head ministries and represent its interests in the government. Sometimes ministers with no associated ministry are appointed, known as ministers without portfolio.[142] Estonia has been ruled by coalition governments because no party has been able to obtain an absolute majority in the parliament.[139]

The head of the state is the President who has a primarily representative and ceremonial role. There are no referendums on the election of the president, but the president is elected by the Riigikogu, or by a special electoral college.[143] The President proclaims the laws passed in the Riigikogu, and has right to refuse proclamation and return law in question for a new debate and decision. If Riigikogu passes the law unamended, then the President has right to propose to the Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional. The President also represents the country in international relations.[139][144]

The Constitution of Estonia also provides possibility for direct democracy through referendum, although since adoption of the constitution in 1992 the only referendum has been the referendum on European Union membership in 2003.[145]

Estonia has pursued the development of the e-government, with 99 percent of the public services being available on the web 24 hours a day.[146] In 2005 Estonia became the first country in the world to introduce nationwide binding Internet voting in local elections of 2005.[147] In 2023 parliamentary elections 51% of the total votes were cast over the internet, becoming the first time when more than half of votes were cast online.[148]

In the most recent parliamentary elections of 2023, six parties gained seats at Riigikogu. The head of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas, formed the government together with Estonia 200 and Social Democratic Party, while Conservative People's Party, Centre Party and Isamaa became the opposition.[149][150]

القانون

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law, establishing the constitutional order based on five principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social state, and the Estonian identity.[151] Estonia has a civil law legal system based on the Germanic legal model.[152] The court system has a three-level structure. The first instance are county courts which handle all criminal and civil cases, and administrative courts which hear complaints about government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance are district courts which handle appeals about the first instance decisions.[153] The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, conducts constitutional review, and has 19 members.[154] The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can be removed from office only when convicted of a crime.[155] The justice system has been rated among the most efficient in the European Union by the EU Justice Scoreboard.[156] As of June 2023, gay registered partners and married couples have the right to adopt. Gay couples will gain the right to marriage in Estonia in 2024. Estonia is the first of the former Soviet republics to legalize same-sex marriage.[157][158]

العلاقات الخارجية

Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from 22 September 1921, and became a member of the United Nations on 17 September 1991.[159][160] Since restoration of independence Estonia has pursued close relations with the Western countries, and has been member of NATO and the European Union since 2004.[160] In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 the Eurozone.[160] The European Union Agency for large-scale IT systems is based in Tallinn, and started operations at the end of 2012.[161] Estonia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.[162]

Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with Latvia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. Estonia is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly, the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.[163] Estonia has built close relationship with the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and is a member of Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8).[160][164] Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the education programme Nordplus[165] and mobility programmes for business and industry[166] and for public administration.[167] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with a subsidiaries in Tartu and Narva.[168][169] The Baltic states are members of Nordic Investment Bank, European Union's Nordic Battle Group, and in 2011 were invited to co-operate with Nordic Defence Cooperation in selected activities.[170][171][172][173]

The beginning of the attempt to redefine Estonia as "Nordic" was seen in December 1999, when then Estonian foreign minister (and President of Estonia from 2006 until 2016) Toomas Hendrik Ilves delivered a speech entitled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs,[174] with the potential political calculation behind it being the wish to distinguish Estonia from its more slowly progressing southern neighbours, which could have postponed early participation in European Union enlargement.[175] Andres Kasekamp argued in 2005, that relevance of identity discussions in Baltic states decreased with their entrance into EU and NATO together, but predicted, that in the future, attractiveness of Nordic identity in Baltic states will grow and eventually, five Nordic states plus three Baltic states will become a single unit.[175]

Other Estonian international organisation memberships include OECD, OSCE, WTO, IMF, the Council of the Baltic Sea States,[160][176][177] and on 7 June 2019, was elected a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for a two-year term that began on 1 January 2020.[178]

Since the Soviet era, the relations with Russia remain generally cold, even though practical co-operation has taken place in between.[179] Since 24 February 2022, the relations with Russia have further deteriorated when Russia made its invasion on Ukraine. Estonia has very actively supported Ukraine during the war, providing highest support relative to its gross domestic product.[180][181]

Military

The Estonian Defence Forces consist of land forces, navy, and air force. The current national military service is compulsory for healthy men between ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8- or 11-month tours of duty, depending on their education and position provided by the Defence Forces.[182] The peacetime size of the Estonian Defence Forces is about 6,000 persons, with half of those being conscripts. The planned wartime size of the Defence Forces is 60,000 personnel, including 21,000 personnel in high readiness reserve.[183] Since 2015 the Estonian defence budget has been over 2% of GDP, fulfilling its NATO defence spending obligation.[184]

The Estonian Defence League is a voluntary national defence organisation under management of Ministry of Defence. It is organised based on military principles, has its own military equipment, and provides various different military training for its members, including in guerilla tactics. The Defence League has 17,000 members, with additional 11,000 volunteers in its affiliated organisations.[185][186]

Estonia co-operates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives. As part of Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) the three countries manage the Baltic airspace control center, Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and a joint military educational institution Baltic Defence College is located in Tartu.[187]

Estonia joined NATO in 2004. NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008.[188] In response to Russian war in Ukraine, since 2017 a NATO Enhanced Forward Presence battalion battle group has been based in Tapa Army Base.[189] Also part of NATO Baltic Air Policing deployment has been based in Ämari Air Base since 2014.[190] In European Union Estonia participates in Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.[191][192]

Since 1995 Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo, and Mali.[193] The peak strength of Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009.[194] 11 Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions of Afghanistan and Iraq.[195]

التقسيمات الإدارية

خطأ: الصورة غير صحيحة أو غير موجودة

Estonia is a unitary country with a single-tier local government system. Local affairs are managed autonomously by local governments. Since administrative reform in 2017, there are in total 79 local governments, including 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities. All municipalities have equal legal status and form part of a maakond (county), which is an administrative subunit of the state.[196] Representative body of local authorities is municipal council, elected at general direct elections for a four-year term. The council appoints local government. For towns, the head of the local goverment is linnapea (mayor) and vallavanem for parishes. For additional decentralization the local authorities may form municipal districts with limited authority, currently those have been formed in Tallinn and Hiiumaa.[197]

Separately from administrative units, there are also settlement units: village, small borough, borough, and town. Generally, villages have less than 300, small boroughs have between 300 and 1000, boroughs and towns have over 1000 inhabitants.[197]

السياسة

إستونيا هي دولة دستورية ديمقراطية. رئيس الجمهورية هو أعلى منصب سياسي يُنتخب من برلمان الدولة (Riigikogu) ،ذو المجلس الأحادي، كل خمس سنوات. الحكومة ، اللتي تتشكل من 14 وزير، هي الذراع التنفيذي للرئيس. الحكومة تُعين من الرئيس بعد موافقة البرلمان عليها. البرلمان يتكون من 101 نائب، اللذين ينتخبوا كل أربع سنوات بشكل مباشر من الشعب. المحكمة القضائية العليا هي المحكمة الوطنية (Riigikohus)، اللتي تتكون بدورها من 17 قاضي يرأسهم رئيس القضاة اللذي يعين من البرلمان.

البرلمان

الحكومة

القانون

العلاقات الخارجية

العسكرية

الاقتصاد

بعد إنتهاء الحقبة الشيوعية بالبلاد حولت إستونيا نظامها الاقتصادي تدريجياً، آخذة اقتصاديات الدول الاسكندنافية كمثل أعلى لها، اللتي تمتاز بقلة البيروقراطية ، شفافية أنظمة الدولة و اتصالات حديثة. الاقتصاد الإستوني أصبح ينمو بسرعة و ثقة أكثر بعد دخول البلاد بالاتحاد الاوروبي عام 2004. أهم الصناعات هي الغذائية و الكهربائية. أيضاً صيد الأسماك و صناعة الأثاث لهم دور مهم بدفع عجلة النمو و زيادة الصادرات. أهم الشركاء التجاريين هم الدول الاسكندنافية و خاصة فنلندا.

إستونيا كانت إحدى الدول الرائدة لإدخال نظام ضريبي فريد من نوعه (عام 1994) يقضي باستقتطاع 26% من دخل الفرد كضريبة دخل بغض النظر عن مهنته، لاحقاً تم خفضها إلى 24%.

الطرق البرية و الملاحة البحرية هي أهم سبل المواصلات في البلاد. تُستعمل السكك الحديدية بشكل رئيسي لنقل البضائع. الموانئ البحرية الكبيرة تتواجد في العاصمة تالين و بارنو. يخترق الطريق السريع شارع البلطيق (Via Baltica) من جنوب البلاد إلى شمالها.

التنمية التاريخية

الموارد

الصناعة والبيئة

التجارة

| إستونيا (2014[199]) | الصادرات | الواردات |

|---|---|---|

| السويد | 18% | 11% |

| فنلندا | 14% | 15% |

| لاتفيا | 10% | 9% |

| روسيا | 9% | 6% |

| لتوانيا | 5% | 8% |

| ألمانيا | 5% | 10% |

| نرويج | 4% | -% |

| الولايات المتحدة | 4% | -% |

| هولندا | 3% | 4% |

| الصين | -% | 4% |

الديموغرافيا

حسب احصائيات عام 2002 فإن 67.9% من سكان البلاد هم استونيون، يليهم الروس بنسبة 25.6%، ثم الأوكرانيين (2.1%)، الروسيون البيض (1.2%) و الفنلنديون (0.9%). الجالية الروسية تتركز حول العاصمة تالين و في شمال شرق البلاد.

التمدن

الديانات

المسيحية اللوثرية (75%)، تليها الأرثوذوكسية الروسية (14%),اليهودية (أقل من 1%).

| الدين | تعداد 2000 [202] | تعداد 2011[203] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| العدد | % | العدد | % | |

| مسيحيون أرثوذكس | 143,554 | 12.80 | 176,773 | 16.15 |

| مسيحيون لوثريون | 152,237 | 13.57 | 108,513 | 9.91 |

| معمدانيون | 6,009 | 0.54 | 4,507 | 0.41 |

| روم كاثوليك | 5,745 | 0.51 | 4,501 | 0.41 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 3,823 | 0.34 | 3,938 | 0.36 |

| Old Believers | 2,515 | 0.22 | 2,605 | 0.24 |

| Christian Free Congregations | 223 | 0.02 | 2,189 | 0.20 |

| Earth Believers | 1,058 | 0.09 | 1,925 | 0.18 |

| Taara Believers | 1,047 | 0.10 | ||

| Pentecostals | 2,648 | 0.24 | 1,855 | 0.17 |

| مسلمون | 1,387 | 0.12 | 1,508 | 0.14 |

| Adventists | 1,561 | 0.14 | 1,194 | 0.11 |

| بوذيون | 622 | 0.06 | 1,145 | 0.10 |

| Methodists | 1,455 | 0.13 | 1,098 | 0.10 |

| ديانات أخرى | 4,995 | 0.45 | 8,074 | 0.74 |

| بلا ديانة | 450,458 | 40.16 | 592,588 | 54.14 |

| لم يفصح | 343,292 | 30.61 | 181,104 | 16.55 |

| الإجمالي1 | 1,121,582 | 100.00 | 1,094,564 | 100.00 |

1السكان، والأشخاص أكبر من 15 والمسنون.

المجتمع

اللغات

اللغة الاستونية، لغة البلاد الرسمية، لا تتبع اللغات البلطيقية و انما مجموعة اللغات الفنلندية-المجرية. الروسية تُستعمل بين أبناء الجالية الروسية في البلاد.

التعليم والعلوم

الثقافة

الأدب

الإعلام

الموسيقى

العمارة

العطلات العامة

المطبخ

الرياضة

الترتيبات الدولية

| المؤشر | الترتيب | الدول المشاركة |

|---|---|---|

| Freedom House Internet Freedom 2012 | 1st | 47 |

| Global Gender Gap Report Global Gender Gap Index 2013 | 59th | 136 |

| Index of Economic Freedom 2014 | 11th | 157 |

| Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2011–2012 | 11th | 187 |

| State of World Liberty Index 2006 | 1st | 159 |

| Human Development Index 2013[204] | 33rd | 169 |

| Corruption Perceptions Index 2013 | 28th | 176 |

| Networked Readiness Index 2014 | 21st | 133 |

| Ease of Doing Business Index 2014 | 22nd | 158 |

| State of The World's Children's Index 2012[205] | 10th | 165 |

| State of The World's Women's Index 2012 | 18th | 165 |

| World Freedom Index 2014[206] | 8th | 165 |

| Legatum Prosperity Index 2011 | 33rd | 110 |

| EF English Proficiency Index 2013 | 4th | 60 |

| Programme for International Student Assessment 2012 (Maths) | 11th | 65 |

| Programme for International Student Assessment 2012 (Science) | 6th | 65 |

| Programme for International Student Assessment 2012 (Reading) | 11th | 65 |

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Estonia Census 2021". Statistics Estonia. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 November 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Extraordinary year for population statistics". Statistics Estonia. 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.[dead link]

- ^ "Population census: Estonia's population and the number of Estonians have grown". Statistics Estonia. June 1, 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-04-16.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income". EU-SILC survey. Eurostat. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF) (in الإنجليزية). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Definition of Estonia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 29 October 2013. /ɛˈstoʊniə,_ɛˈstoʊnjə/

- ^ "Define Estonia". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 29 October 2013. /ɛˈstoʊniə,_ɛˈstoʊnjə/

- ^ Estonian Republic at the Internet Archive. Official website of the Republic of Estonia (in Estonian)

- ^ Matthew Holehouse Estonia discovers it's actually larger after finding 800 new islands The Telegraph, 28 August 2015

- ^ "Country Profile – LegaCarta". Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ See, for instance, position expressed by European Parliament, which condemned "the fact that the occupation of these formerly independent and neutral States by the Soviet Union occurred in 1940 following the Molotov/Ribbentrop pact, and continues." European Parliament (January 13, 1983). "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C 42/78.

- ^ "Estonian Economic Miracle: A Model For Developing Countries". Global Politician. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2020: Estonia" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2020.

- ^ "Estonia (Ranked 21st)". Legatum Prosperity Index 2020.

- ^ "Pisa rankings: Why Estonian pupils shine in global tests". BBC News. 2 December 2019.

- ^ "Estonia among top 3 in the UN e-Government Survey 2020". e-Estonia. 24 July 2020.

- ^ Harold, Theresa (October 30, 2017). "How A Former Soviet State Became One Of The World's Most Advanced Digital Nations". Alphr. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Number of start-ups per capita by country". 2020.stateofeuropeantech.com.

- ^ Germania, Tacitus, Chapter XLV

- ^ "Spell it "ESTHONIA" here; Geographic Board Will Not Drop the "h," but British Board Does". New York Times. 17 April 1926. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Ineta Ziemele (20 March 2002). Baltic yearbook of international law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-90-411-1736-6. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ^ أ ب Laurisaar, Riho (31 July 2004). "Arheoloogid lammutavad ajalooõpikute arusaamu" (in الإستونية). Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 23. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 24. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 26. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Selirand, Jüri; Tõnisson, Evald (1984). Through past millennia: archaeological discoveries in Estonia. Perioodika.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 4. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 28. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 68. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ^ Tvauri, Andres (2012). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. pp. 33, 34, 59, 60. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Mäesalu, Ain (2012). "Could Kedipiv in East-Slavonic Chronicles be Keava hill fort?" (PDF). Estonian Journal of Archaeology. 1 (16supplser): 199. doi:10.3176/arch.2012.supv1.11. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 9–11. ISBN 9780230364509.

- ^ Enn Tarvel (2007). Sigtuna hukkumine Archived 11 أكتوبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine Haridus, 2007 (7–8), pp. 38–41

- ^ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in الإستونية). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 286. ISBN 9985701151.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 90. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ أ ب Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ^ أ ب Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in الإستونية). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 287. ISBN 9985701151.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 93. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 91. ISBN 9042008903.

- ^ أ ب Cultural Policy in Estonia. Council of Europe. 1997. p. 23. ISBN 9789287131652.

- ^ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in الإستونية). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 291. ISBN 9985701151.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in الإستونية). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 292. ISBN 9985701151.

- ^ Calvert, Peter (1987). The Process of Political Succession. Springer. p. 67. ISBN 9781349089789.

- ^ Calvert, Peter (1987). The Process of Political Succession. Springer. p. 68. ISBN 9781349089789.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 9781403919557.

- ^ Pinder, David (1990). Western Europe: Challenge and Change. ABC-CLIO. p. 75. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ^ أ ب Pinder, David (1990). Western Europe: Challenge and Change. ABC-CLIO. p. 76. ISBN 9781576078006.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 9781403919557.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2000). The Radical Right in Interwar Estonia. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 9781403919557.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780810875135.

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second edition, updated. Hoover Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ^ Leonard, Raymond W. (1999). Secret Soldiers of the Revolution: Soviet Military Intelligence, 1918–1933. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 34–36. ISBN 9780313309908.

- ^ Bell, Imogen (2002). Central and South-Eastern Europe 2003. Psychology Press. p. 244. ISBN 9781857431360.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1983). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940–1980. University of California Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780520046252.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ أ ب van Ginneken, Anique H. M. (2006). Historical Dictionary of the League of Nations. Scarecrow Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780810865136.

- ^ von Rauch, Georg (1974). Die Geschichte der baltischen Staaten. University of California Press. pp. 108–111. ISBN 9780520026001.

- ^ Hiden, John; Lane, Thomas (2003). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780521531207.

- ^ Åselius, Gunnar (2004). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Navy in the Baltic 1921–1941. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 9781135769604.

- ^ Lane, Thomas; Pabriks, Artis; Purs, Aldis; Smith, David J. (2013). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 9781136483042.

- ^ Gärtner, Heinz (2017). Engaged Neutrality: An Evolved Approach to the Cold War. Lexington Books. p. 125. ISBN 9781498546195.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-8108-7513-5.

- ^ Hiden, John; Salmon, Patrick (2014). The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-317-89057-7.

- ^ Raukas, Anto (2002). Eesti entsüklopeedia 11: Eesti üld (in الإستونية). Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus. p. 309. ISBN 9985701151.

- ^ Johnson, Eric A.; Hermann, Anna (May 2007). "The Last Flight from Tallinn" (PDF). Foreign Service Journal. American Foreign Service Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2012.

- ^ Mälksoo, Lauri (2003). Illegal Annexation and State Continuity: The Case of the Incorporation of the Baltic States by the USSR. Leiden – Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-411-2177-3.

- ^ أ ب Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8108-7513-5.

- ^ Gatrell, Peter; Baron, Nick (2009). Warlands: Population Resettlement and State Reconstruction in the Soviet-East European Borderlands, 1945–50. Springer. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-230-24693-5.

- ^ Kaasik, Peeter; Raudvassar, Mika (2006). "Estonia from June to October, 1941: Forest brothers and Summer War". In Hiio, Toomas; Maripuu, Meelis; Paavle, Indrek (eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 496–517.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence by Anatol Lieven p424 ISBN 0-300-06078-5

- ^ Lane, Thomas; Pabriks, Artis; Purs, Aldis; Smith, David J. (2013). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-136-48304-2.

- ^ Pinder, David (1990). Western Europe: Challenge and Change. ABC-CLIO. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8108-7513-5.

- ^ "Conclusions of the Commission". Estonian International Commission for Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. 1998. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-136-45213-0.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Scarecrow Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-8108-6571-6.

- ^ أ ب Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8179-2853-7.

- ^ Kangilaski, Jaan; et al. (2005). Salo, Vello (ed.). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 9789985701959.

- ^ Kasekamp, Andres (2010). A History of the Baltic States. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-230-36450-9.

- ^ Kangilaski, Jaan; et al. (2005). Salo, Vello (ed.). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers. p. 30. ISBN 9789985701959.

- ^ Kangilaski, Jaan; et al. (2005). Salo, Vello (ed.). The white book: losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes, 1940–1991. Estonian Encyclopaedia Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 9789985701959.

- ^ Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1983). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940–1980. University of California Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-520-04625-2.

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). Estonia and the Estonians: Second Edition, Updated. Hoover Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780817928537.

- ^ Purs, Aldis (2013). Baltic Facades: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania since 1945. Reaktion Books. p. 335. ISBN 9781861899323.

- ^ أ ب Taagepera, Rein (2013). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the Russian State. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 9781136678011.

- ^ Puur, Allan; Rahnu, Leen; Sakkeus, Luule; Klesment, Martin; Abuladze, Liili (22 March 2018). "The formation of ethnically mixed partnerships in Estonia: A stalling trend from a two-sided perspective" (PDF). Demographic Research. 38 (38): 1117. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.38. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Misiunas, Romuald (1983). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence: 1940-1990. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-520-04625-2. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Misiunas, Romuald (1983). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence: 1940-1990. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-520-04625-2. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 227. ISBN 9780810875135.

- ^ Spyra, Wolfgang; Katzsch, Michael (2007). Environmental Security and Public Safety: Problems and Needs in Conversion Policy and Research after 15 Years of Conversion in Central and Eastern Europe. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 14. ISBN 9781402056444.

- ^ Stöcker, Lars Fredrik (2017). Bridging the Baltic Sea: Networks of Resistance and Opposition during the Cold War Era. Lexington Books. p. 72. ISBN 9781498551281.

- ^ Lepp, Annika; Pantti, Mervi (2013). "Window to the West: Memories of watching Finnish television in Estonia during the Soviet period". VIEW (in الإنجليزية). Journal of European Television History and Culture (3/2013): 80–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Feldbrugge, F. J. Ferdinand Joseph Maria; Van den Berg, Gerard Pieter; Simons, William Bradford (1985). Encyclopedia of Soviet Law. BRILL. p. 461. ISBN 9789024730759.

- ^ Lane, Thomas; Pabriks, Artis; Purs, Aldis; Smith, David J. (2013). The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Routledge. p. xx. ISBN 9781136483042.

- ^ Frankowski, Stanisław; Stephan III, Paul B. (1995). Legal Reform in Post-Communist Europe: The View from Within. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 9780792332183.

- ^ Backes, Uwe; Moreau, Patrick (2008). Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe: Schriften Des Hannah-Arendt-Instituts Für Totalitarismusforschung 36. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 9. ISBN 9783525369128.

- ^ Vogt, Henri (2005). Between Utopia and Disillusionment: A Narrative of the Political Transformation in Eastern Europe. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 20–22. ISBN 9781571818959.

- ^ Simons, Greg; Westerlund, David (2015). Religion, Politics and Nation-Building in Post-Communist Countries. Ashgate Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 9781472449719.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. pp. 46–48. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Walker, Edward W. (2003). Dissolution: Sovereignty and the Breakup of the Soviet Union. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 63. ISBN 9780742524538.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Smith, David (2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 9781136452130.

- ^ Gill, Graeme (2003). Democracy and Post-Communism: Political Change in the Post-Communist World. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 9781134485567.

- ^ Dillon, Patricia; Wykoff, Frank C. (2002). Creating Capitalism: Transitions and Growth in Post-Soviet Europe. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 164. ISBN 9781843765561.

- ^ Nørgaard, Ole (1999). The Baltic States After Independence. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 188. ISBN 9781843765561.

- ^ Ó Beacháin, Donnacha; Sheridan, Vera; Stan, Sabina (2012). Life in Post-Communist Eastern Europe after EU Membership. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 9781136299810.

- ^ "Estonia and the WTO". World Trade Organization. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9780810875135.

- ^ "Estonia and OECD". Estonia in OECD.

- ^ "Estonia becomes 17th member of the euro zone". BBC News. 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Estonia in the UN Security Council | Ministry of Foreign Affairs". vm.ee.

- ^ Estonian Mires Inventory[dead link] Compiled by Jaanus Paal and Eerik Leibak. Estonian Fund for Nature. Tartu, 2011

- ^ "Hiking Route: Aegviidu-Ähijärve 672 km - Loodusega koos RMK". Loodusega Koos. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRaukas_2018 - ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEEA - ^ "Climate normals - Temperature". Estonian Environment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Weather records - Temperature". Estonian Environment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Climate normals - Precipitation". Estonian Environment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Weather records - Precipitation". Estonian Environment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ "Climate normals - Sunshine". Estonian Environment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- ^ أ ب Taylor, Neil (2014). Estonia. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 4, 6–7. ISBN 9781841624877.

- ^ Timm, Uudo; Maran, Tiit (March 2020). "How much has the mammal fauna in Estonia changed?". Loodusveeb. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Peep Männil: Läänemaal elab veel vähemalt kaks šaakalit, tõenäoliselt rohkem". Maaleht. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Einmann, Andres (1 September 2017). "Šaakalite jahihooaeg pikenes kahe kuu võrra". Postimees. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Neil (2014). Estonia. Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9781841624877.

- ^ Spilling, Michael (2010). Estonia. Marshall Cavendish. p. 11. ISBN 9781841624877.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ "National Flower". Global Road Warrior. World Trade Press. 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Nature conservation". Ministry of the Environment. 13 July 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Toots, Anu (March 2019). "2019 Parliamentary elections in Estonia" (PDF). Friedrich Ebert Foundation. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ "What is Riigikogu?". Riigikogu. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ "What does Riigikogu do?". Riigikogu. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Annus, Taavi (27 September 2012). "Government". Estonica. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ YLE: Viron presidentinvaali on ajautumassa kaaokseen jo toista kertaa peräkkäin – "Instituutio kyntää pohjamudissa", sanoo politiikan tutkija (in Finnish)

- ^ Annus, Taavi (27 September 2012). "Duties of the President of the Republic". Estonica. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Liivik, Ero (2011). "Referendum in the Estonian Constitution" (PDF). Juridica International. 18: 21. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ Schulze, Elizabeth (8 February 2019). "How a tiny country bordering Russia became one of the most tech-savvy societies in the world". CNBC. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Vinkel, Priit (2012). "Information Security Technology for Applications". 7161: 4–12, Springer Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-29615-4_2.

- ^ "Estonia sets new e-voting record at Riigikogu 2023 elections". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. 6 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ "Reform Party takes landslide win in 2023 Riigikogu elections". 6 March 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "Reformierakonna, Eesti 200 ja Sotsiaaldemokraatide valitsus astus ametisse" (in Estonian). Eesti Rahvusringhääling. 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ernits, Madis; et al. (2019). "The Constitution of Estonia: The Unexpected Challenges of Unlimited Primacy of EU Law". In Albi, Anneli; Bardutzky, Samo (eds.). National Constitutions in European and Global Governance: Democracy, Rights, the Rule of Law. The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press. p. 889. doi:10.1007/978-94-6265-273-6. hdl:10138/311890. ISBN 978-94-6265-272-9.

- ^ Varul, Paul (2000). "Legal Policy Decisions and Choices in the Creation of New Private Law in Estonia" (PDF). Juridica International. 5: 107. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Madise, Ülle (27 September 2012). "Courts of first instance and courts of appeal". Estonica. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Supreme Court of Estonia". Supreme Court of Estonia. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Heydemann, Günther; Vodička, Karel (2017). From Eastern Bloc to European Union: Comparative Processes of Transformation since 1990. Berghahn Books. p. 12. ISBN 9781785333187.

- ^ Vahtla, Aili (6 June 2018). "Study: Estonian judicial system among most efficient in EU". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Estonia becomes first former Soviet nation to legalize same-sex marriage". 22 June 2023.

- ^ "Estonian government approves draft same-sex marriage act". ERR News (in الإنجليزية). 2023-05-15. Retrieved 2023-06-06.

- ^ Whittaker Briggs, Herbert (1952). The law of nations: cases, documents, and notes. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 106.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Estonia country brief". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "EU Agency for large-scale IT systems". European Commission. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Estonian presidency leaves 'more confident' EU". EUobserver. 21 December 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Estonian Chairmanship of the Baltic Council of Ministers in 2011". Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Nordic-Baltic Co-operation". Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Nordplus". Nordic Council of Ministers. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "NordicBaltic Mobility and Network Programme for Business and Industry". Nordic Council of Ministers' Office in Latvia. Archived from the original on 18 November 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "NordicBaltic mobility programme for public administration". Nordic Council of Ministers' Office in Estonia. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Nordic Council of Ministers' Information Offices in the Baltic States and Russia". Nordic Council of Ministers. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Norden in Estonia". Nordic Council of Ministers' Office in Estonia. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania 10-year owners at NIB". Nordic Investment Bank. December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Smyth, Patrick (7 May 2016). "World View: German paper outlines vision for EU defence union". The Irish Times. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Dahl, Ann Sofie; Järvenpää, Pauli (2014). Northern Security and Global Politics: Nordic-Baltic strategic influence in a post-unipolar world. Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-415-83657-9. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "NORDEFCO annual report 2015" (PDF). Nordefco.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ Ilves, Toomas Hendrik (14 December 1999). "Estonia as a Nordic Country". Estonian Foreign Ministry. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ أ ب Mouritzen, Hans; Wivel, Anders (2005). The Geopolitics of Euro-Atlantic Integration (1 ed.). Routledge. p. 143.

- ^ "List of OECD Member countries – Ratification of the Convention on the OECD". OECD. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Participating States". OSCE. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Gallery: Estonia gains non-permanent UN Security Council seat". ERR News. ERR. 7 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Ambassador: Successes tend to get ignored in Estonian-Russian relations". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Estonia's Prime Minister: 'We Need to Help Ukraine Win'". Foeign Policy. 3 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Updates: Russia's invasion of Ukraine – reactions in Estonia". Estonian World. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ "Compulsory military service". Estonian Defence Forces. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "Estonian Defence Forces". Estonian Defence Forces. Retrieved 28 December 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Kaitse-eelarve" (in الإستونية). Estonian Ministry of Defence. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "Estonian Defence League". Estonian Defence League. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ McLaughlin, Daniel (8 July 2016). "Baltic volunteers guard against threat of Russian stealth invasion". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Vahtla, Aili (20 April 2017). "Defense chiefs decide to move forward with Baltic battalion project". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Whyte, Andrew (5 May 2019). "Nine more nations join NATO cyberdefense center". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (10 July 2017). "Nato sends 'alive and strong' message from Estonia". BBC. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Czechs and Belgians take over in latest Baltic air police rotation". LSM. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Andresson, Jan Joel (17 February 2015). "If not now, when? The Nordic EU Battlegroup". European Union Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Estonia joins European Intervention Initiative". Estonian Ministry of Defence. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Operatsioonid alates 1995" (in الإستونية). Estonian Defence Forces. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "Eesti sõdurite 10 aastat Afganistanis: 9 surnut, 90 haavatut". Postimees (in الإستونية). 15 March 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Rohemäe, Maria-Ann (27 April 2014). "Välisoperatsioonidel on hukkunud 11 Eesti sõdurit" (in الإستونية). Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Pesti, Cerlin; Randma-Liiv, Tiina (April 2018). "Estonia". In Thijs, Nick; Hammerschmid, Gerhard (eds.). Public administration characteristics and performance in EU28. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. pp. 252–255. doi:10.2767/74735. ISBN 9789279904530.

- ^ أ ب "Local Governments". Estonian Ministry of Finance. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Pentland, William (26 August 2013). "World's 39 Largest Electric Power Plants". Forbes. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ [1] الإحصائيات الإستونية

- ^ "Population by ethnic nationality, 1 January, year". stat.ee. Statistics Estonia. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ أعلى مبنى في إستونيا

- ^ "PC231: POPULATION BY RELIGIOUS AFFILIATION AND ETHNIC NATIONALITY". Statistics Estonia. 31 March 2000. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "PC0454: AT LEAST 15-YEAR-OLD PERSONS BY RELIGION, SEX, AGE GROUP, ETHNIC NATIONALITY AND COUNTY, 31 DECEMBER 2011". Statistics Estonia. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHDI - ^ "Nutrition in the First 1,000 Days: State of the World's Mothers 2012" (PDF). Savethechildren.org. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "World Freedom Index". Retrieved 27 March 2015.

المراجع

- Jaak Kangilaski et al. (2005) Valge raamat (1940–1991), Justiitsministeerium, ISBN 9985-70-194-1.

قراءات إضافية

- Giuseppe D'Amato Travel to the Baltic Hansa. The European Union and its enlargement to the East. Book in Italian. Viaggio nell'Hansa baltica. L'Unione europea e l'allargamento ad Est. Greco&Greco editori, Milano, 2004. ISBN 88-7980-355-7

- Hiden, John; Patrick Salmon (1991). The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-08246-3.

- Laar, Mart (1992). War in the Woods: Estonia's Struggle for Survival, 1944–1956. trans. Tiina Ets. Washington, D.C.: Compass Press. ISBN 0-929590-08-2.

- Lieven, Anatol (1993). The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the Path to Independence. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05552-8.

- Raun, Toivo U. (1987). Estonia and the Estonians. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 0-8179-8511-5.

- Smith, David J. (2001). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26728-5.

- Smith, Graham (ed.) (1994). The Baltic States: The National Self-determination of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-12060-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Taagepera, Rein (1993). Estonia: Return to Independence. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1199-3.

- Taylor, Neil (2004). Estonia (4th ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt. ISBN 1-84162-095-5.

- Williams, Nicola; Debra Herrmann; Cathryn Kemp (2003). Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (3rd ed.). London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-132-1.

- Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (Ed.) (2004). Estonia, identity and independence. Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi. ISBN 90-420-0890-3.

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about Estonia at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Definitions from Wiktionary | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

| Textbooks from Wikibooks | |

| Learning resources from Wikiversity | |

- الحكومة

- The President of Estonia

- The Parliament of Estonia

- Estonian Government

- Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Statistical Office of Estonia

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- السياحة

- Official gateway to Estonia

- E-Estonia Portal

- VisitEstonia Portal

- إستونيا travel guide from Wikivoyage

- خرائط

- google.com map of Estonia

- Geographic data related to إستونيا at OpenStreetMap

- معلومات عامة

- Encyclopedia Estonica

- Estonian Institute

- Estonia entry at The World Factbook

- BBC News – Estonia country profile

- Estonia at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Estonia at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of Estonia

- أخبار

- الطقس والتوقيت

The average temperature ranges between −10C and 20C (14F and 68F). [link http://www.emhi.ee/index.php?ide=6&g_vaade=param&id=1]